Gulzar: The 10 Commandments That Shaped My Life

Faith, fate, and the giants who shaped him—the veteran poet and screenwriter shares the tenets that guide his life with Esquire India

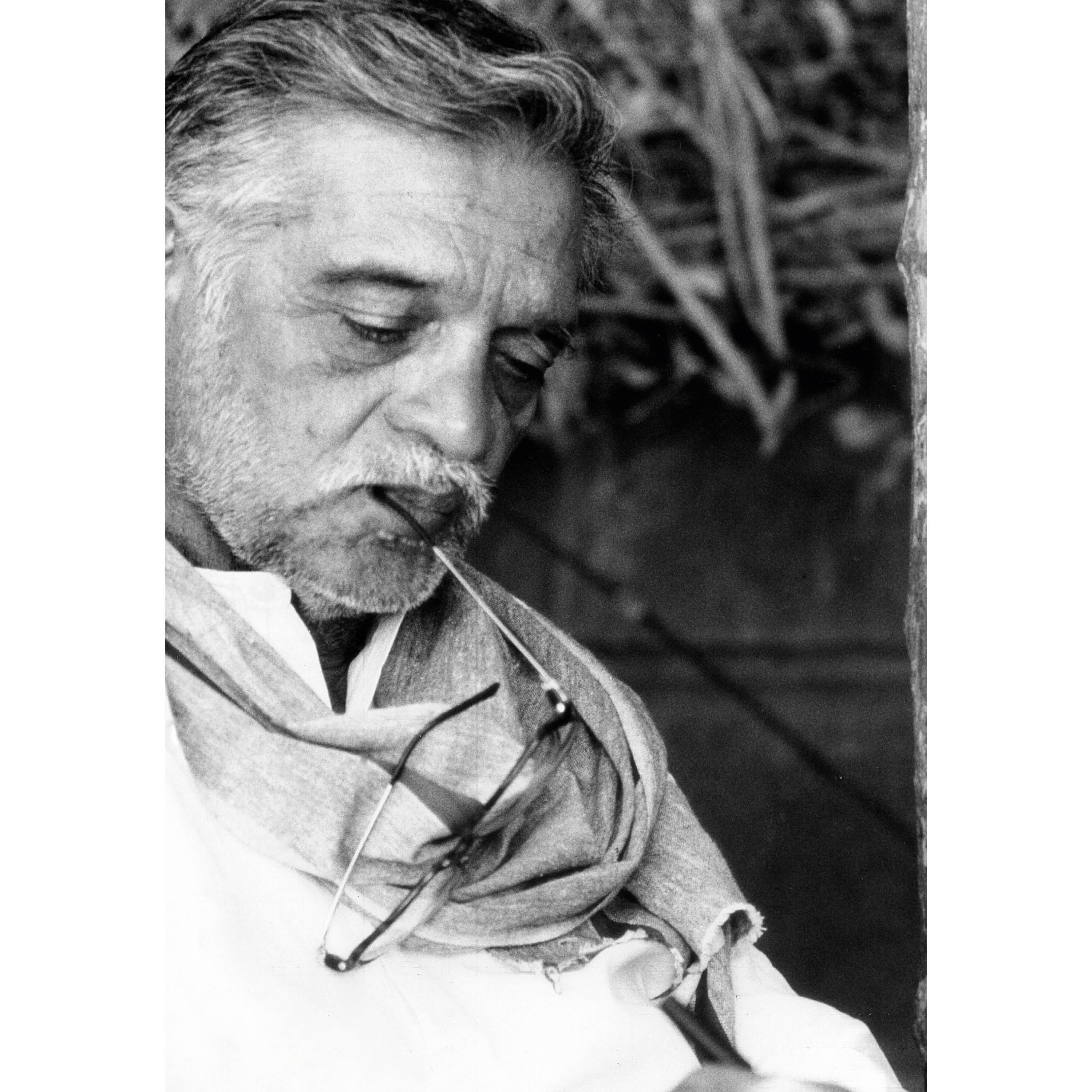

Veteran screenwriter and renowned poet Gulzar has shaped films, TV serials, and songs for over six decades, his turn of phrase instantly recognisable. To map his body of work is to trace the chronology of memorable Indian cinema—and that’s without even accounting for his vast literary and translation oeuvre. Who better, then, to launch Esquire India’s What I’ve Learnt, a series that distils the hard-won wisdom of remarkable individuals—what life has taught them, the truths they hold onto and the conclusions they’ve drawn from extraordinary experiences.

Looking back on 90 autumns... if you can keep the deadweight of nostalgia out of the equation, it can be a rewarding experience. Look a poem decades after its composition. You will react to it in a new way. Just as human hormones change with age, so do the hormones of poems. They mutate with time. The words will sound different, they will evoke distinct emotions. It is the same with people who have drifted in and out of your life and the events that have unfolded. I can scarcely believe that the Gulzar sitting at the desk writing this is the same person who shared the same space as Pandit Ravi Shankar in the music room, or the one who wrote the screenplay for Mahasweta Devi’s novel, or the one who walked the streets of New York with [poet] Dilip Chitre, or the one who sat in the chaotic space of an Irani hotel with [poet] Namdeo Dhasal…

You May Also Like: Hrithik Roshan Is The Cover Star Of Esquire India’s Inaugural Issue

Our childhood shapes us in ways we cannot even begin to fathom. We carry it in our hearts all our life. My childhood memories are imbued with the horrors of the Partition. I still remember the boy who led our school prayers being dragged through the streets of Delhi by a mob, out of our sight, and the leader of the group returning with a blood-stained sword. Even decades later, I would wake up with nightmares of the madness I witnessed. I was too scared even to cry. For a long time, I could not write about it, but then it is the act of writing that has helped me cope, enabled me to purge some of the poison. No wonder the Partition has influenced my writing in such a big way. No wonder I keep harping on the artificiality of man-made borders.

Aankhon ko visa nahin lagta

Sapnon ki sarhad hoti nahin

Band aankhon se roz sarhad paar chala jata hun

Milne Mehdi Hassan se

Sunta hun unki aawaz ko chot lagi hai

Aur ghazal khamosh hai samne baithi hui

Kaanp rahe hain honth ghazal ke

Jab kehte hain…

Sookh gaye hain phool kitabon mein

Yaar Faraz bhi bichhad gaye

Ab shayad miley wo khwaabon mein!

Band aankhon se roz sarhad paar chala jata hun

Aankhon ko visa nahin lagta

Sapno ki sarhad koi nahin

Eyes don’t need a visa

Dreams have no borders

Eyes closed, I cross the border every day

To meet Mehdi Hassan

I have heard that his voice is injured

And the ghazal sits in front of him, mute

Her lips tremble

When he says…

‘The flowers have dried in the pages of books

My friend Faraz, too, is gone, will meet him in my dreams perhaps.’

Eyes closed, I often cross the border.

Eyes don’t need a visa

Dreams have no borders

(Aankhon Ko Visa Nahin Lagta, translated by Rakhshanda Jalil)

I have had a prickly relationship with God. I have always addressed him with the playful moniker Bade Miyan. But I have refused to believe in His omnipresence or benevolence. You cannot outsource your creativity to God. You have to live your own experiences to write about them. God cannot do that for you. As we have seen, God cannot even protect devotees who seek refuge in his abode. I am engaged in a game of hide-and-seek with him—only, I have the sneaking suspicion that he is the one perpetually hiding from me.

Bura laga toh hoga aye Khuda tujhe

Dua mein jab

Jamhai le raha tha main!

Dua ke is amal se thak gaya hoon main

Main jab se dekh-sun raha hoon

Tab se yaad hai mujhe

Khuda jalaa-bujha raha hain raat din

Khuda ke haath mein hain sab bura bhala

Dua karo

Ajeeb sa amal hai yeh

Yeh ek farzi guftugu

Aur ek-tarfa–ek aise shakhs se

Khayal jiski shakl hai

Khayal hi saboot hai!

O God, you must be feeling bad

I yawned

While praying!

I am tired of this act of praying

Ever since I have been watching and hearing

I remember

God switches on and off night and day

God holds

All goodness and all evil

Pray to God

It is a strange practice

This imaginary conversation

And one sided too—with a being

Whose form exists in our imagination

And whose proof too lies in our imagination

(God-1, translated by Rakhshanda Jalil)

I did not actively strive for a particular writing style. I believe in what TS Eliot said about the art of writing—keep it as close to conversation as possible. I have tried to adhere to that. That is probably what people mean when they speak about my ‘style’, the informal, imbued with the simplicity of the quotidian experience. It is not easy; being simple is the toughest part of being a writer. Behind every poem are hours and days of agonising over one word, one turn of phrase; I am a glorified munshi who sits at his desk from 10 in the morning to six in the evening—only, instead of dealing in the debits and credits of monetary transactions, I dwell in the whys and hows of the human condition. And the human balance sheet and profit and loss never tally. The ‘style’, if there is any, has evolved organically.

Your language needs to evolve with the times and reflect the age you're writing in. Languages die when they do not walk in step with the times. In an era of WhatsApp and emojis, you cannot express love in words like ‘Tu Ganga ki mauj main Jamuna ki dhara’. Does ‘Main tulsi tere aangan ki’ have any relevance when we live in high-rises devoid of tulsis and aangans? In contrast, ‘Aankhen personal se sawaal karti hain’ invokes the spirit of the times.

You May Also Like: Hrithik Roshan: The Myth, The Man, The Moment

At the same time, it must engage with the concerns of the times. Otherwise, it becomes sterile. I cannot sit in the confines of my ivory tower and still hope for my writing to resonate. That is why everything that happens around me is an inspiration for what I write—nature, environment, the plight of our workers and farmers, the political and social situation. Even Neil Armstrong, for whom I wrote a poem when he stepped off the earth and went far beyond the moon, in 2012.

Kitni baar akele chhat pe jaake chaand ko dekhta tha

Aur mazaak kiya karta tha…

‘Baayan paer zameen par hai aur daayan paer wahin rakkha hai,

Yaar haath badhao…

Jhuk ke haath pakad lo, yaar, aur upar kheench lo

Ek paer pe khade-khade main thakne laga hoon!’

Pehla paaon jisne chaand pe rakkha tha

Doosra paaon aaj zameen se utha liya, aur

Chaand se aage nikal gaya!

Innumerable times he would go up to the terrace to

look at the moon and say jokingly,

‘The left foot is on the earth and the right one is right there

My friend, stretch your hand

And bending down, hold my hand and pull me up

It’s tiring to keep standing on one foot.’

He who placed the first foot on the moon

Has lifted his other foot off the earth

And gone far beyond the moon.

(Neil Armstrong, translated by Sathya Saran)

The only time I made a deliberate effort to develop a special form was with my Trivenis. People mistake these for haikus. The word triveni refers to the confluence of three distinct streams or rivers at Prayag. A Triveni discusses an image in the first couplet and in the concluding line makes an unexpected contextual revelation. The deep green waters of Jamuna meet the golden Ganga and hidden from from view is the mythical Saraswati flowing quietly beneath. The first two lines are the Ganga and Jamuna, expressing a train of thought. The third line reveals the hidden Saraswati poetically and completes the Triveni.

Sab pe aati hai, sab ki baari se

Maut munsif hai, kam-o-besh nahin

Zindagi sab pe kyon nahin aati?

It visits us all, without fail, when it’s time

Death is just—there’s nothing less or more about it

Why doesn’t life visit everyone in all fairness?

(Translated by Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri)

My writing for cinema has shaped my non-film writing and vice-versa. In the early days, writing for film was an impediment to literary success as the literary world looked down on writing in cinema. However, these lyrics are an art form in their own right. Are Bob Dylan’s songs any less than the poetry of Keats and Wordsworth? My film writing reflects my sensibility. I am aware of the demands of the narrative and the character when I write for cinema. I know that a gangster, winding down with a drink after a long day, will not sing ‘Dil-e-naadan tujhe hua kya hai’. He will be more in the mood for ‘Goli maar bheje mein’. Recognising that is as much an artistic choice as my poem on Michelangelo’s La Pietà. So, JK [Sanjeev Kumar’s character in Aandhi] singing ‘Tere bina zindagi se koi shikwa toh nahin’ is as much an artistic rendition as ‘Beedi jalai le’.

Evolution lies at the core of a fulfilling life. Even in my relationship with my daughter, I have always made it a point to evolve. I cannot presume to know better or more than my child. I might be biologically older but in my experience as a father I am only as old as she is. Both need to learn and evolve together. This has been at the core of my writing for children. The ability to relate to them at their level, not looking down on them—the bane of most Indian writing for children.

Like Isaac Newton, if I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants. Tagore was instrumental in me stealing the first book I ever took—an Urdu translation of The Gardener. Subconsciously that set me on my literary path. Seventy years later, life came full circle when I would publish my own translation of The Gardener as Baaghbaan. Ghalib and Neruda were influential voices that shaped me. Bimal Roy took a young man entirely uninterested in cinema under his wings and gave him flight. A new world opened up for me with geniuses like Salil Chowdhury and RD Burman. Years later, Rekha Bhardwaj, AR Rahman, Vishal Bhardwaj, Shankar Mahadevan held my hand and opened new ways of looking at the world. Working on gigantic projects like A Poem a Day, translating 365 poems from 34 languages and dialects of the Indian subcontinent, introduced me to poets young and old, men and women, from across the Indian subcontinent.

As told Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri