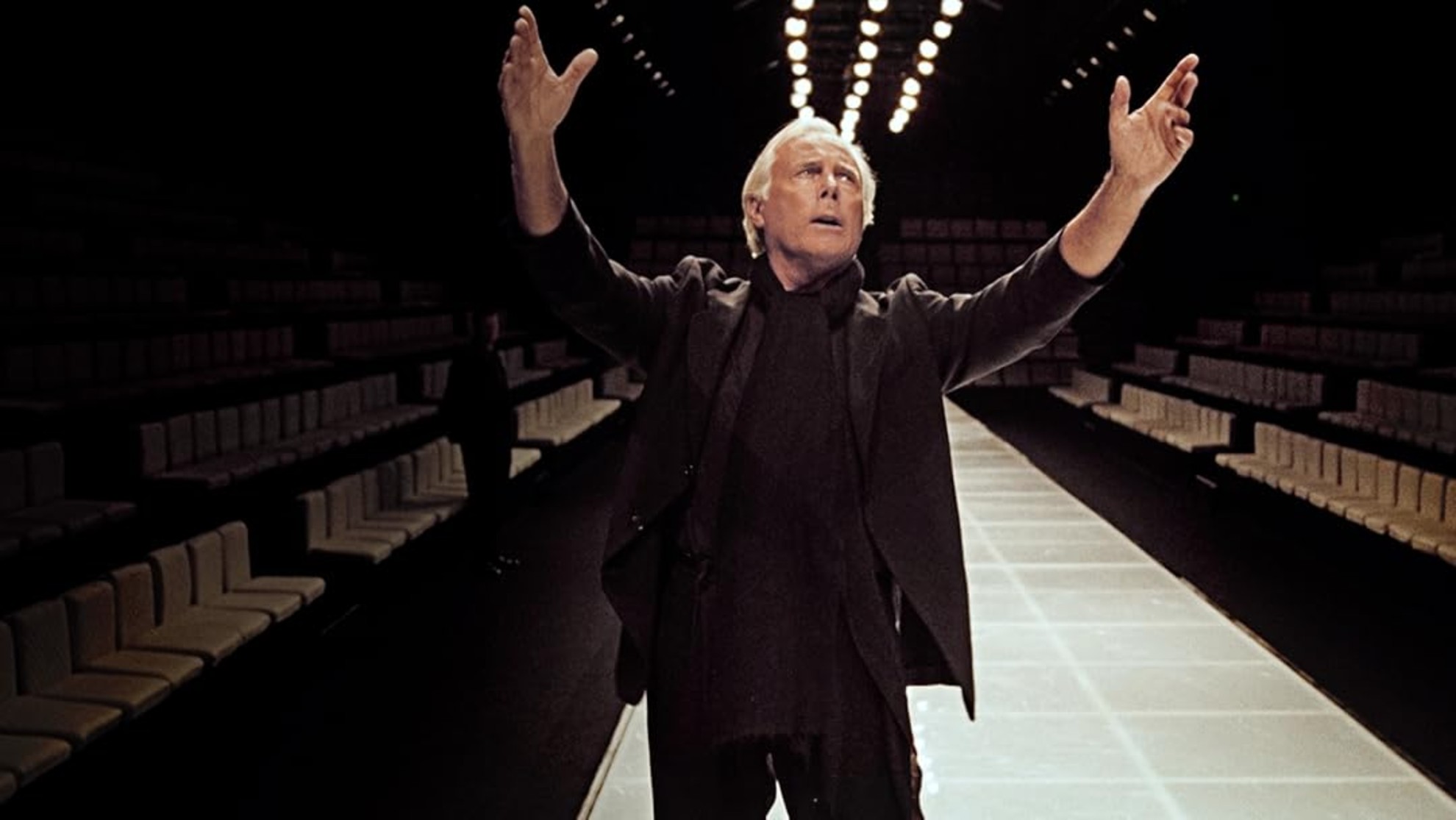

Re Giorgio: The Last Emperor of Elegance Has Died At 91

With the death of Giorgio Armani at 91, the world loses one of the last great architects of 20th-century style

For nearly half a century, Giorgio Armani defined what it meant to look powerful without appearing to try. He was the architect of the deconstructed suit, the godfather of Hollywood’s red-carpet modernity, the rare designer whose name meant the same thing in Milan, New York, or Tokyo: elegance stripped down to its essence. On Thursday, Armani died at 91, his company announced, after a long period of declining health. With him goes not just a man, but one of the last surviving architects of late-20th-century style.

Armani wasn’t Dior with his New Look, or Saint Laurent with his cultural shocks. His revolution was quieter, but no less seismic: he convinced the world that authority could be soft. The Armani jacket—sloped shoulders, buttons dropped just so, fabric that moved like water—wasn’t merely clothing; it was a manifesto against rigidity. If the 1980s belonged to pinstripes and suspenders, Armani made them fluid, even sensual. For women, his power suits did what Coco Chanel’s tweed once had—rewrote the visual language of ambition.

From Piacenza to Milan

To understand Armani’s obsession with control and restraint, you have to start in Piacenza in the 1930s. Born in 1934, Giorgio was the second of three children in a modest family. His childhood was punctured by World War II: bombings, scarcity, a father forced to join Mussolini’s party, a brother caught up in fascist youth squads. Armani himself nearly lost his sight after a childhood accident with leftover gunpowder from an artillery shell. For years afterwards, he admitted, he would fling himself into ditches whenever a plane passed overhead.

These scars mattered. They gave Armani an aversion to excess, to loudness, to chaos. Later he would say, “Elegance is not about being noticed, it’s about being remembered.” That belief wasn’t just aesthetic; it was forged in wartime Piacenza.

In the 1950s the family moved to Milan. Armani studied medicine briefly, worked in a hospital during military service, then drifted into La Rinascente, the city’s grande department store, where he dressed windows before graduating to fabrics and buying. It was there he first absorbed how clothes communicate. By the mid-1960s, he was designing menswear under Nino Cerruti, learning tailoring from the ground up.

A Late Start, A Meteoric Rise

Unlike most prodigies of fashion, Armani was a late bloomer. He founded his own label at 41, selling his Volkswagen Beetle to raise capital. His partner, Sergio Galeotti, an architect with a belief in Armani’s eye, convinced him to take the leap. Together they launched Giorgio Armani S.p.A. in 1975. Galeotti became chairman, Armani the creative heart.

The speed of their ascent was extraordinary. Within a decade, Armani was a household name, his jackets hanging in the closets of both Wall Street bankers and Hollywood stars. In 1982, just seven years after that first women’s collection, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine—only the second designer in history, after Dior, to receive the honour. The headline read: “Giorgio’s Gorgeous Style.” Armani had, in less than a decade, rewritten the world’s uniform.

Tragedy came early too. Galeotti died of AIDS-related complications in 1985, a loss Armani rarely discussed. In interviews he described Galeotti as the person who “made me believe in myself.” After his death, Armani became both creative director and CEO, one of the few designers to retain complete ownership and control over a global empire.

Hollywood’s Favourite Tailor

If Paris belonged to couture and London to eccentricity, Milan, through Armani, became synonymous with cinematic cool. His break came with Richard Gere in American Gigolo (1980). Here was a new kind of seduction: masculine, but not stiff; luxurious, but not gaudy. The film turned Armani into shorthand for a kind of modern sex appeal, one rooted in subtlety rather than flash. Soon, Hollywood stars, Oscar attendees, and entire film casts — Goodfellas, The Wolf of Wall Street, The Untouchables — were stepping onto red carpets and screens draped in Armani.

From there, there was Sharon Stone in a crisp white shirt at the Oscars, Julia Roberts’s red carpet glamour, Michelle Pfeiffer in sleek tailoring, Robert De Niro’s understated mob boss in Goodfellas, Cate Blanchett’s statuesque elegance—these were Armani moments as much as cinematic ones. He dressed more than 200 films, but more importantly, he redefined what stardom looked like. Gone were the theatrical costumes of old Hollywood; Armani made stars look like people. People who just happened to be gods.

It was also cultural diplomacy. In the 1980s and ’90s, when America consumed Italy through cinema, Armani became its most potent export—every bit as important as Fellini or Ferrari. If Versace was the flamboyance of Milan, Armani was its discipline. Both changed the world.

The Armani Elegance

Critics sometimes accused Armani of repetition, of redrawing the same suit endlessly. But that was the point.

He was too busy perfecting the idea of a suit. Season after season, he returned to the suit as an eternal form, refining its shoulder line, rethinking its fluidity, insisting that restraint could be a radical gesture.

And that philosophy travelled. Armani built an empire across Emporio Armani, Armani Exchange, Armani Casa, even Armani Hotels in Dubai and Milan. Wherever he expanded, the codes remained the same: quiet palettes, fluid lines, no spectacle for its own sake. The Armani name became a kind of shorthand for globalised taste.

Unlike most of his peers, he never sold out to LVMH or Kering. He remained the sole shareholder of his company, steering it with obsessive control into his ninth decade. Even this June, too ill to attend Milan Men’s Fashion Week for the first time in his career, he laid out a succession plan, carefully passing responsibilities to his closest confidants.

Now, Armani leaves behind a business empire worth billions, but more importantly, he leaves a philosophy: that style is about reduction.

“Elegance,” he once said, “isn’t about being noticed. It’s about being remembered.”

And he sure will be.