The Lost Art Of Flirting

In the age of “hey u up?”, modern men have forgotten how to woo

It was sometime after midnight, in a dimly lit bar (you know, low lamps, velvet booths, sultry music, a pianist playing music that sounded just like foreplay) when I watched a man walk up to a woman in an attempt to get her number.

He was handsome in a generic, well-fed way. She was alert, amused, open to it. The conditions were definitely favourable.

And then the man opened his mouth and out came the words: “You remind me of my mother.” Like. Sir? Excuse me? What now?

She feigned a laugh, although I could tell she was waiting to get rid of him in the first 30 seconds of the conversation. And then after some forced small talk, she asked him where the bathroom was, and disappeared.

He stayed at the bar, chest puffed, surveying the room with the quiet pride of a man who believed he had done something tonight. Poor guy.

Flirting has always been a strange, charged ritual; like a performance, or a confession.

Like when peacock’s open up their feathers and dance in front of peahens to encourage sexual mating. It is the moment in which a man places himself, deliberately and visibly, in another person’s emotional weather. It demands presence, timing, an ability to read tone and hesitation in real time. Most of all, it demands the willingness to be refused. It is the moment in which a man says, without saying it, I am risking myself here.

And for most of human history, this risk could not be outsourced.

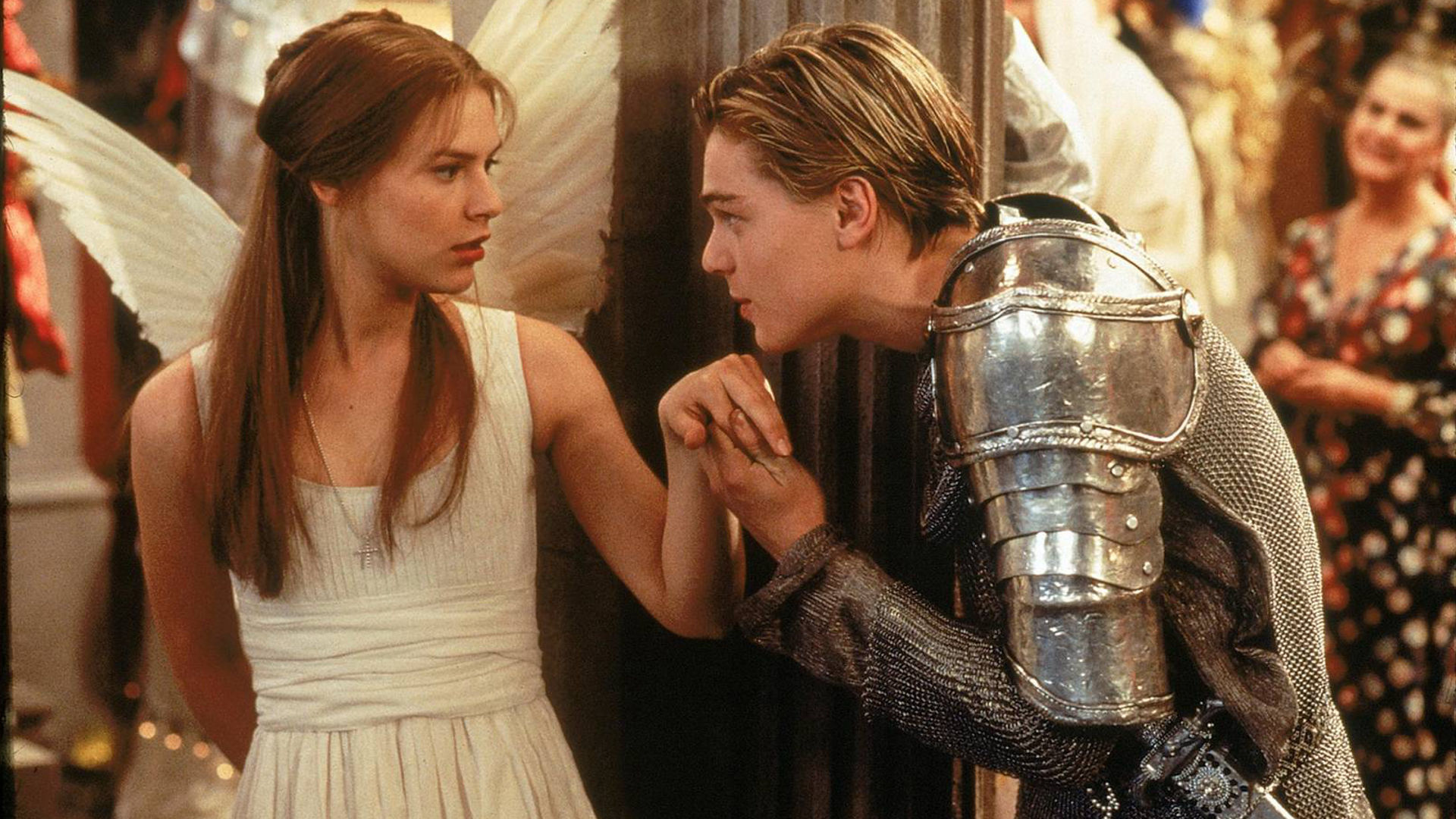

Courtship demanded effort because effort was the signal. In the nineteenth century, men wrote letters that took weeks to arrive. In Edwardian England, you paid calls and left cards. Jane Austen’s Darcy spent hours writing letters. Romeo stood under Juliet's balcony just to say the famous words, "It is the east, and Juliet is the sun. / Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon / Who is already sick and pale with grief, / That thou, her maid, art far more fair than she."

Think of Heathcliff pacing the moors in Wuthering Heights, undone not by rejection but by time—years of it, stretching longing into something feral. Or Levin in Anna Karenina, spelling out his proposal with chalked initials across a card table, a coded confession that had us in the twists. Even Gatsby, that gaudy avatar of modern excess, builds an entire mythos—houses, parties, reputation—just to be seen again by Daisy for five quiet minutes.

In mid-century America, you phoned a landline and hoped her father didn’t answer. In Indian cities, men lingered outside college gates, passed notes across library tables, waited on scooters beneath balconies. Even the early internet era—MSN, Orkut, long emails sent at 2 a.m.—still required composition, timing, and nerve. I mean, You’ve Got Mail is a cult classic for a reason people.

When my father was courting my mother, he actually bought her a plug-in landline for her room so they could talk for hours without my grandfather finding out. It's a true story.

Across centuries and mediums, attraction once unfolded through friction: waiting, wondering, risking misinterpretation. Love had texture because it had obstacles.

Eva Illouz, in Consuming the Romantic Utopia, argued that modern romance has always been shaped by technology—from the novel to the cinema to the telephone—but that each shift preserved a sense of narrative and anticipation. What we have now, she writes in later work like Cold Intimacies, is something different: a culture that treats emotional life as a marketplace. Choice is abundant, attachment provisional, and intimacy increasingly “disembedded” from physical presence.

Dating apps did not kill desire, they just flattened its terrain.

Attraction was once a situation you entered. You noticed someone. You hesitated. You rehearsed. You crossed a room. The outcome was unknown. Now attraction is a notification. The approach is a field. The opening line is a placeholder: “Hey.” “What’s up.” “You’re hot.” Even sincerity has become modular. You can prompt a machine to sound charming, vulnerable, poetic; and thus, it will oblige.

But vulnerability without risk is just theatre.

Barry Schwartz’s The Paradox of Choice demonstrated that abundance erodes commitment. When options multiply, satisfaction collapses. We hesitate longer. We invest less. Dating platforms operate on this logic. They encourage browsing over choosing. Everyone is potentially replaceable; no one is irreplaceable.

Pew Research has shown that a majority of young adults now meet partners online, and that ghosting has become a normative experience. Stanford sociologist Michael Rosenfeld, who tracks how couples form, notes that online dating has surpassed friends and family as the primary matchmaker. Romance has become infrastructural.

For men, this has quietly rewired behaviour.

Today, many men are fluent in optimisation but illiterate in tone. They can build brands, negotiate salaries, curate profiles, but essentially freeze in front of a woman. They confuse bluntness with honesty, assume attraction should be frictionless, and feel cheated when it isn’t. The digital man is trained not to linger. Why risk embarrassment when silence costs nothing? Why craft a sentence when ten generic ones might land somewhere?

People for that, flirting, at its best, is not cleverness. It is attention.

It lives in micro-adjustments: a joke softened mid-sentence, a pause extended, a glance held or released. It is improvisation. You cannot pre-write it because it changes with every breath the other person takes. It is reciprocal by definition.

Cinema once understood this. The entire architecture of Before Sunrise is flirtation as philosophy—two strangers talking their way into each other. When Harry Met Sally treats banter as erotic gravity. Even Call Me By Your Name lingers on glances, silences, weather. The tension is the whole point.

However, today, more recent films like Her capture the anxiety of mediated intimacy—a man in love with a voice, safe from the chaos of another body. It’s telling that these stories now feel nostalgic. We aestheticise what we no longer practise.

Sherry Turkle, in Alone Together, argues that technology gives us the illusion of companionship without the demands of relationship. We are “connected,” she writes, but protected from the mess of real presence. Flirting is messy. It exposes you. It can bruise.

The modern system has engineered the bruise out.

And yet the hunger persists. You see it in the resurgence of speed-dating events, in “offline” clubs, in the cultural obsession with meet-cutes. We still long to be chosen in real time. To be seen by a person who is there.

Flirting does not require sonnets or grand gestures (although I’m not opposed to a good old sonnet). It requires courage. It is choosing a line because it fits her, not because it performs well in aggregate.

We’re not peacocks anymore. We’re monkeys with Wi-Fi. And what’s the fun in that?