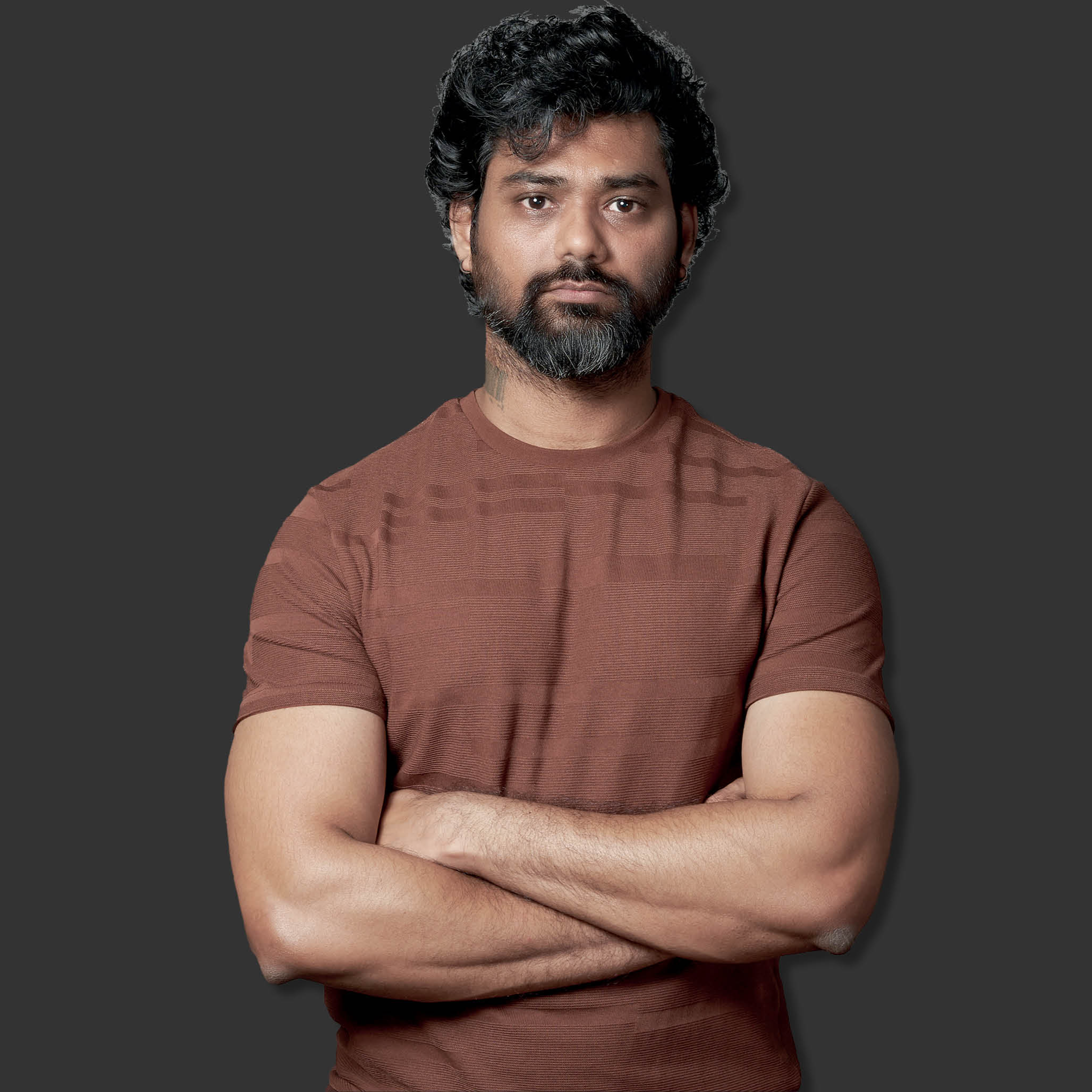

Director-Screenwriter Rohan Kanawade On Leading The Charge For A New Kind Of Queer Storytelling

Rohan Kanawade's Sabar Bonda is the first Marathi film at Sundance and the winner of a Grand Jury Prize

Towards the end of Sabar Bonda, his directorial feature, Balya (Suraaj Suman), the farmer, tells his father he’s going to be off to the city. Who will he live with? His ‘special friend’, Anand (Bhushaan Manoj), who’s visiting the village to perform funerary rituals for his father. The father’s nostrils flare, but Balya’s quiet determination wins. In one of the closing shots, the two men are captured at the back of a night bus taking them to Mumbai.

The breakout Marathi film, which won the Grand Jury Prize (World Cinema: Dramatic) at Sundance this year, unfolds gently around Anand as he fends off incessant questioning from relatives about marriage. Even as he quietly battles this and his current state of grief, the 30-year-old finds warmth and comfort in the company of Balya, his school buddy. “I always dreamt of taking my first feature film, made in my mother tongue, to one of the world’s top festivals. Being selected for Sundance was already a dream come true, but the prize was beyond anything I had hoped for,” he says.

You May Also Like: Highly Recommended Movies To Watch Based on True Events

Kanawade, who also wrote the film, recalls that a screen consultant at a film lab suggested that the protagonists publicly standing up to the whole village would make for a bold statement.

“She loved it, and then she said, ‘Rohan, you know, Anand and Balya go back Mumbai too quietly. They should stand in front of the village and relatives and declare their love’—but I was like, no. I’m not making that kind of a film—to which she responded, ‘Oh, you don’t realise the power of cinema!’” he recalls. “But so many people have lived their lives without standing up in that way.”

He is opposed to that brand of storytelling where social message is part of content strategy. Kanawade chooses, instead, to make visible the quotidian existence of his characters.

“I didn’t want to show an imagined version of queer life—but how it is, most of the time. You have your experiences, which are real. Why can’t you use them to create something?” asks the filmmaker, who was born and raised in a Mumbai slum by a chauffeur father and a homemaker mother. Despite going on to study interior design at the behest of his father’s employer, he remembers being charmed by films as a young child.

“Film projectors fascinated me. As a 10-year-old, I built my own slide projector inside a shoebox,” says Kanawade, who grew up with the burning hankering to tell stories on his favourite medium. A few years after completing school, he borrowed a friend’s phone and PC to shoot and edit his first short for a filmmaking competition.

On screen as well as culturally, coming out is often framed as a fraught experience. But in Kanawade’s experience, the acceptance from his parents, despite them lacking the cosmopolitan exposure that we think necessary, was instant. In the film, too, this personal triumph translates to Anand’s mother colluding with him every step of the way in safeguarding his vulnerability and offering freely the sort of parental encouragement and generosity that often become so important in pursuing love without baggage.

Which is how he also procured for his onscreen masculinity the gentleness and understanding that he experienced in his own life. “My father was strict when I was a child. But at a certain point, he said, ‘Now I won’t yell at you or hit you. You are my friend now’. Popular films want to show masculinity in a certain way, but men are also gentle.”

The film’s initial title was Arms of a Man. In one of its scenes that stays with you, Anand and Balya hold each other in a lingering, unclothed embrace in the forest. Moments before, you have seen Balya rub his hands together to hug Anand by the riverside, after the duo goes for a winter swim. “I could have shown them having sex, but I didn’t want to show that. But just lying with each other, in each other’s arms, was indeed what I wanted to show.”

In his 2019 queer short U Ushacha, unlettered farm labourer Usha takes control of her life and education after she develops an attraction for her children’s English teacher. If there’s any truth to the idea that connection and love can restore some of our lost innocence, both U Ushacha and Sabar Bonda embody it. In the case of the latter, it is evident in the way its protagonists become eager boys in each other’s presence. “When you are that comfortable with someone, you can become like a child again. It’s about connection and comfort,” Kanawade reflects on that tenderness.

You May Also Like: Classic Films Every Man Must Watch

This streak for staging quiet empowerment that doesn’t depend on cinematic spectacles of resistance is probably what drew mythology writer Devdutt Pattanaik to come up and partially fund U Ushacha. For Sabar Bonda, actor Jim Sarbh served as the celebrity co-producer. “We’ve started securing distribution deals in Europe, and I hope the film will continue to reach audiences worldwide. But my biggest dream is for it to be released in India, in its entirety, so that Indian audiences can experience it just as the global audience does.”

Speaking of reception, if revenues are any indication, the theatrical uptake of anything less than sprawling epics seems discouraging currently. As for austere, intelligent stories, the streaming space has become the de facto destination. But if we know anything about Kanawade yet, it’s that he doesn’t give into bold proclamations easily.

“People keep saying audiences won’t go to theatres unless it’s a mass-market film, but I’ve seen All We Imagine as Light (2024) twice in the theatre and both times, theatres were houseful on weekdays! People want to watch good cinema if it’s available,” he says.

These small, unspoken moments of care, often missing from mainstream narratives, are what drive Kanawade’s cinema. He is not interested in confrontation for its own sake. He does not want to create a cinematic moment that declares victory. Instead, he looks for the subtle shifts, the quiet allowances, the lived realities of queer existence that do not need to be loud to be valid. He’s a veritable master of economy.

Rohan Kanawade picks: Five Queer Films To Watch

Stranger By The Lake (2013)

A 40-something man who frequents a lakeside cruising spot and meets an homme fatal. Directed by Alain Guiraudie.

Tropical Malady (2004)

Based on a Thai folk tale, this Apichatpong Weerasethakul diptych is formed of a romance between two men, and a soldier who gets lost in the woods.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

This sweeping Céline Sciamma period epic follows a painter (Noémie Merlant) commissioned to paint a wedding portrait of a woman (Adèle Haenel) on a seaside estate. The condition? The subject must not know.

José (2018)

A directionless 19-year-old in Guatemala, one of the world’s more culturally conservative countries, comes of age after a relationship with a Caribbean immigrant.

Aligarh (2015)

Manoj Bajpayee stars in this poignant and acclaimed biopic of the late Ramchandra Siras, a professor at Aligarh Muslim University, who faced persecution for his sexuality. Directed by Hansal Mehta.

To read more stories from Esquire India's March 2025 issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest newspaper stand or bookstore. Or click here to subscribe to the magazine.