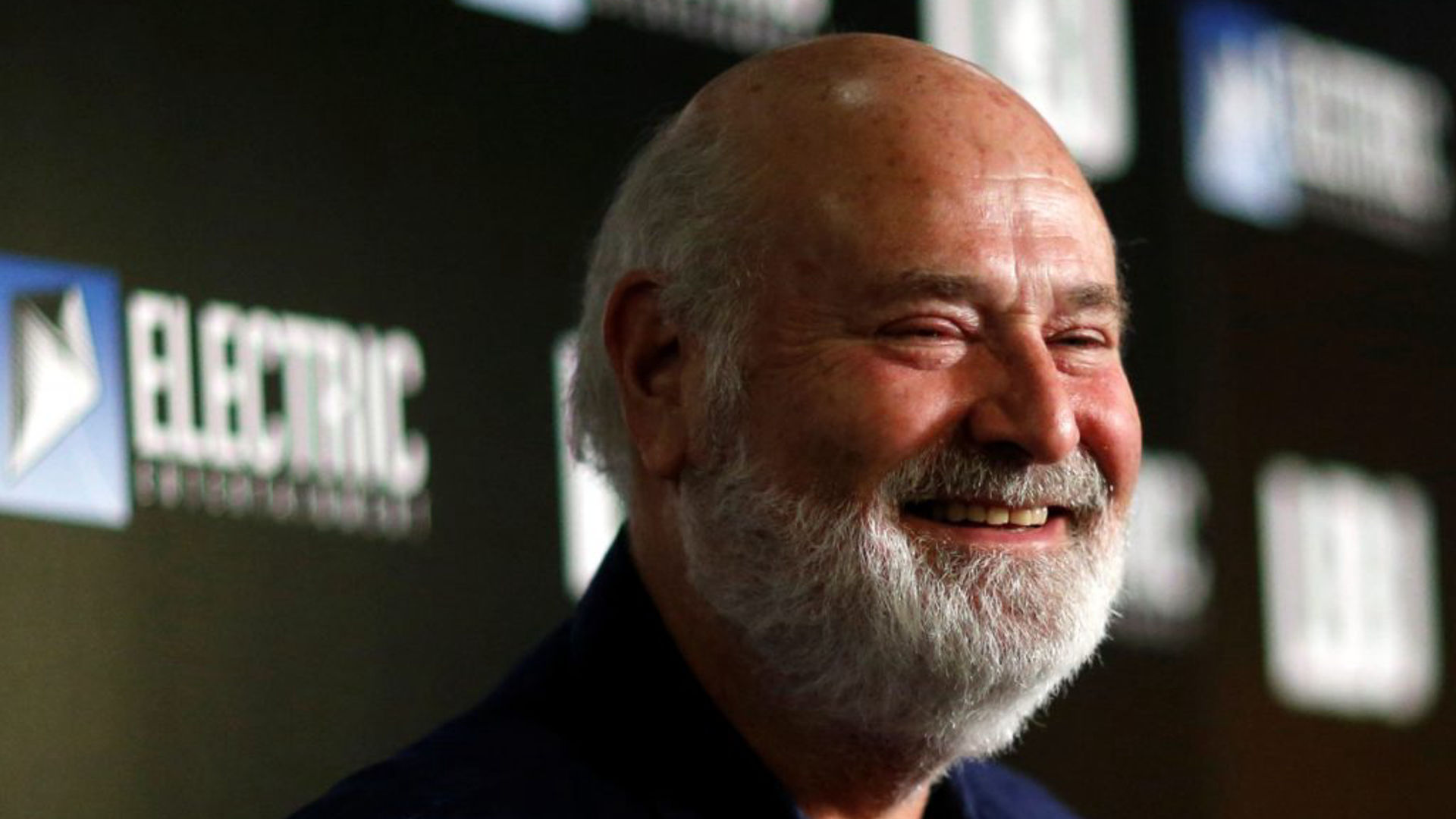

Rob Reiner And The Movies We Grew Up With

Rob Reiner's most enduring films, revisited

Not everyone may know Rob Reiner, but its highly doubtful that you’re not familiar with his long body of work. He was never really out there, announcing himself incessantly, or selling himself as a visionary auteur in the Scorsese or Spielberg mould, but then again – he didn’t need to.

He was too busy quietly rearranging culture when we were busy quoting his lines. For roughly a decade — from the mid-Eighties to the mid-Nineties — Reiner directed film after film that embedded itself so deeply into popular consciousness that it became part of how we speak, flirt, argue, joke, and remember growing up.

He believed, stubbornly and repeatedly, that stories worked best when you trusted actors, trusted audiences, and didn’t over-direct the emotional moments. Across wildly different genres — mockumentary, coming-of-age drama, fairy tale, romantic comedy, courtroom thriller — his films share a fundamental decency. People feel things deeply. They speak too much. They mess up. They try again. And somewhere in the middle of all that noise, connection happens.

His untimely death is shocking, brutal, and impossible to reconcile with the warmth of his work. But his films endure precisely because they resist despair.

This Is Spinal Tap (1984)

Reiner’s first feature as a director is still his most subversive. Shot as a documentary following a fictional British heavy metal band on a disastrous American tour, the film refuses punchlines. It lets reality — or something very close to it — embarrass itself.

Reiner appears onscreen as Marty Di Bergi, the earnest documentarian who believes deeply in the importance of his subject. That sincerity is the film’s engine.

The improvisation — radical for a studio-backed film at the time — gave the movie its loose, lived-in texture. The jokes that survived (“turn it up to eleven,” the tiny Stonehenge, the all-black album cover) didn’t just land; they entered the language. Real musicians recognised themselves in it. Some, famously, thought it was real.

Stand By Me (1986)

Adapted from Stephen King’s novella The Body, the film follows four boys over the course of two days as they walk along railway tracks in 1959 Oregon, searching for the body of a missing child. It’s a simple plot that carries something heavier: the moment when childhood starts slipping away, quietly and without permission.

Reiner directs the boys — Wil Wheaton, River Phoenix, Corey Feldman, Jerry O’Connell — as if they’re already complete people. Their fears, bravado, tenderness, and cruelty are never softened. Phoenix’s Chris Chambers, in particular, is treated with devastating seriousness: a child already marked by class and expectation.

What makes the film endure isn’t nostalgia. It’s honesty. Years later, Reiner would say this was the film closest to his own sensibility. You can feel it. It’s the first time his work stops entertaining and starts remembering.

The Princess Bride (1987)

The Princess Bride is often described as a children’s film. That’s inaccurate.

It’s tempting to reduce this action-romance-fantasy-adventure movie to quotes, because the quotes are perfect. But that misses the point. The film works because Reiner let romance be romantic, adventure be ridiculous, and humour sit alongside real stakes. The movie was a disappointing box-office draw that became a huge cult classic in the decades following its release.

When Harry Met Sally… (1989)

By the late ’80s, the romantic comedy was exhausted — clogged with clichés and tidy endings. When Harry Met Sally… rescued the genre.

The film unfolds across twelve years, following two people who meet, dislike each other, circle each other, and talk — endlessly — about what love and friendship is supposed to mean. Can a man and a woman be friends? Who knows.

The famous moments, like the fake orgasm at Katz’s Delicatessen, the New Year’s Eve run are so deeply embedded in our pop culture today.

Reiner has spoken openly about how making the film changed him. During production, he met photographer Michele Singer. Until then, he’d planned a bleaker ending — Harry and Sally parting ways, unresolved. Meeting Michele altered his understanding of connection. He reshot the ending. Harry runs. Sally waits. They choose each other.

Misery (1990)

Misery, adapted from Stephen King’s novel, traps its characters in a single space and refuses escape. A novelist survives a car crash only to be “rescued” by a fan who decides she owns him. Reiner directs the film with restraint. There’s no excess, no stylised horror. The terror comes from politeness — from smiles that linger too long, from care that curdles into possession.

Kathy Bates’ performance dominates, but Reiner’s contribution is discipline. He never undercuts the fear with humour. The violence shocks because it arrives in a world that initially felt safe.

It’s one of the clearest examples of Reiner’s range.

A Few Good Men (1992)

A Few Good Men looks, on the surface, like a star-driven courtroom drama. What it really is, is a film about responsibility — who takes it, who avoids it, and who hides behind institutions. Working from Aaron Sorkin’s tightly coiled script, Reiner stays out of the way. The film believes, almost stubbornly, that truth matters, even when it’s inconvenient. That belief runs through much of Reiner’s work.

The American President (1995)

Michael Douglas plays a widowed president who falls in love with a lobbyist (Annette Bening) and discovers that intimacy and leadership don’t coexist easily. The politics are idealistic, yes — but they’re also human.

What Reiner gets right is balance. The romance never trivialises the office. The office never suffocates the romance. The film understands power not as spectacle, but as pressure. It also marks the beginning of a language Aaron Sorkin would later perfect on The West Wing.