The first time I was first introduced to sharaab in music wasn't at a nightclub or some boisterous wedding ceremony; it happened in my mother's kitchen with the old radio crooning Ghulam Ali’s Hungama Hai Kyun Barpa Thodisi Jo Peeli Hai. My nine year old mind did not really understand the sadness when he sang, but I had enough understanding to realize this was not just a song about alcohol - it was a lamentation over life's bitterness, quiet joys, and staggering sorrows. Alcohol, it would appear, wasn't merely a liquid in Indian culture. Rather, a metaphor, muse, mirror, and marker of moods.

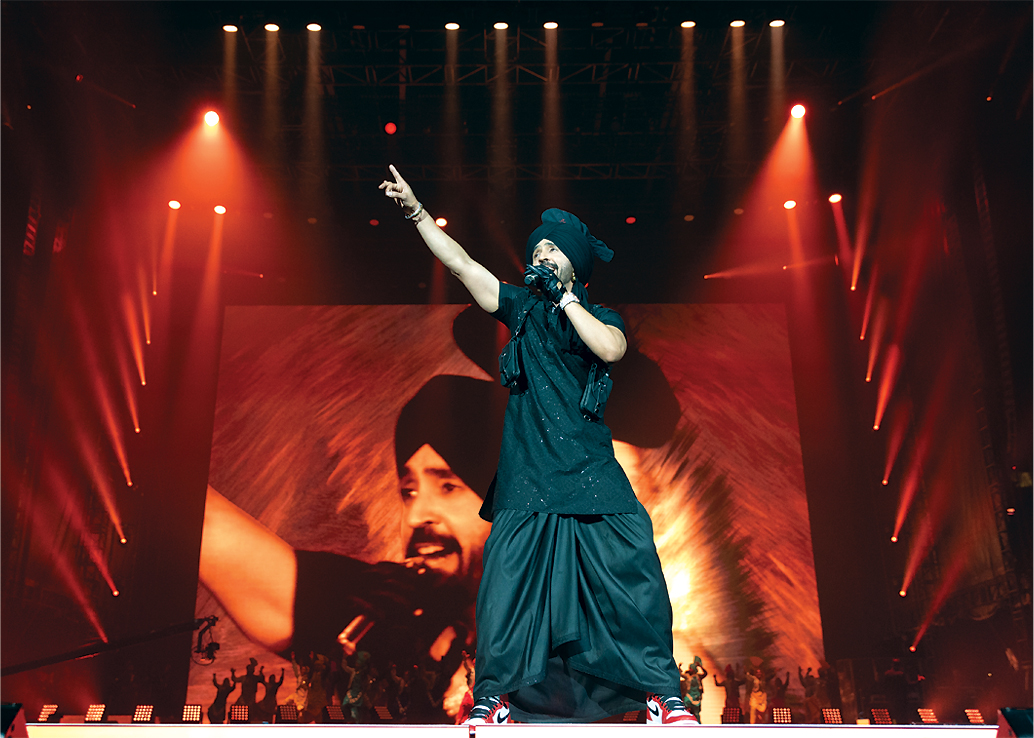

What's ironic is that a country that has been singing about sharaab for decades, can't manage to get its conveniences right without a raised eyebrow from the moral police. Here we are, on the verge of 2025, debating the place of alcohol in art, this time over Diljit Dosanjh's "coke" replacing "peg" in his lyrics during one of the shows in his India tour. Dosanjh's playful lyric swap isn't some macho exercise in callousness but, rather, a survival strategy. On his ongoing India tour, governments in several states have slammed his "alcohol-glorifying" songs, with some even advocating for them not to be performed at all.

You and I can’t be faulted for being conflicted. On one hand, it's hilarious to imagine how his fans would sing along to these sanitized lyrics, and on the other, it almost serves as a sobering reality check into how art, alcohol, and cultural narratives continue to clash in the collective consciousness of India.

A Love Story Through Time

Singing about alcohol isn't new. From Kishore Kumar's iconic Thodi Si Jo Pee Li Hai to Honey Singh's Chaar Bottle Vodka and Badshah's Chhote Chhote Peg, alcohol references have flowed through the veins of Indian music for decades. Folk traditions are no different — Punjabi songs have long celebrated pind da peg as a symbol of joy, camaraderie, and even defiance. Alcohol was never merely a drink; it was an emotional shorthand, a cultural symbol of escapism, celebration, and sometimes despair.

So, what changed? Why are we clutching our pearls now over these lyrics?

Alcohol as Muse

Let's turn the clock back to a time when sharaab hadn't just become one of those words in a song but in fact the actual lifeblood of artistic expression. Amir Khusrau and the absolute masterful works of his qawwalis or the forever timeless ghazals of Mirza Ghalib spring to mind. For them, alcohol was a divine elixir, a sign of spiritual intoxication. When Ghalib wrote, Pila de o saaqi woh mai ke gardish-e-aflaak bhool jaaye, he surely wasn't talking about getting drunk at a bar. Instead, he was invoking wine as a gateway to forget the worldly woes and reach a higher plane of existence. Qawwalis, especially those performed in Sufi shrines, used to talk about the maikhana (tavern) as a metaphor for the abode of the divine, the saaqi (server) as God, and alcohol as pure, spiritual love.

This was an artistic intoxication thrived in a society where alcohol was religiously and morally contentious.

Art on Trial: The Hypocrisy of Outrage

The fire against alcohol in songs sounds all a bit hypocritical when numbers are considered. The alcohol industry in India is worth over $50 billion, and liquor taxes bring in millions into state governments' coffers. It's almost laughable how liquor is marketed at every turn.

Gujarat, Bihar, and Nagaland ban liquor in the name of culture and health, while all those other states line their pockets with handsomely accrued liquor taxes. Alcohol inhabits a strange liminal space — legal in the market, taboo in the cultural imagination.

Perhaps it's easier to ban art than to take on systemic issues. Banning a song is quicker than recognizing a culture where alcohol is both an honoured pastime and a social vice. The backlash against alcohol-themed songs often presents as a convenient distraction. While politicians decry these lyrics for "ruining youth," they fail to note the glaring fact that liquor licenses are handed out like candy. The outrage isn't about protecting the youth, it's about keeping up an appearance of morality behind which they benefit in secret over the nasty perception.

When Dosanjh swapped daaru with coke, it was not just a lyrical replacement but a well-calculated statement. Doing that, he made a sharp remark at how selective and inconsistent our outrage can be. It subtly hits the hypocrisy of a system that lives on alcohol and thereafter comfortably kills its artistic representation. Honestly, calling it Coke does not take away the spirit of the song. If anything, it just adds a layer of cheeky rebellion. It's like a filter over reality: looks different but is basically the same thing.

Music is not the problem, neither is alcohol. The problem lies in the system’s hypocrisy.