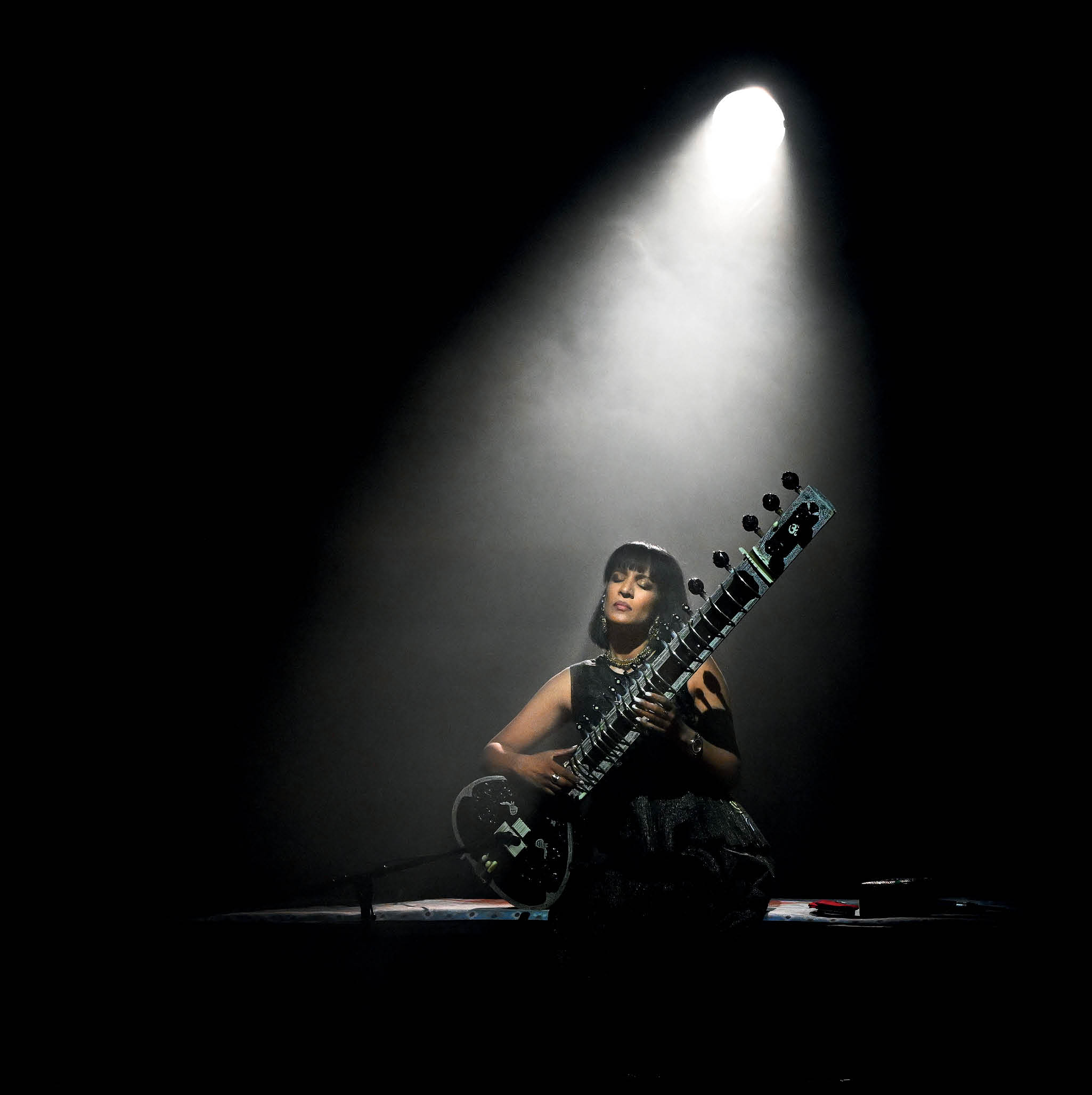

The Many Lives Of Anoushka Shankar

Sitarist Anoushka Shankar looks back on the chapters of her legacy, craft and voice

HER INDIA TOUR IS A FITTING PRELUDE TO A YEAR that marks three decades of Anoushka Shankar on stage. Yes, Anoushka Shankar has been performing live for thirty years, which is a strange thing to say about someone who is still, by any reasonable measure, in the middle of their life. Thirty years of carrying one of the most recognisable surnames in global music—and spending a lifetime refusing to let it define the limits of her imagination.

“This tour comes at a particularly special moment,” she says. “Together, we’ll mark 30 years of sharing my music on stage—three decades of growth, risk and reinvention.”

Her upcoming India tour begins in Hyderabad at the end of January and moves through Bengaluru, Mumbai, Pune, Delhi and Kolkata. Officially, it celebrates both three decades of live performance and the culmination of her Chapters trilogy, a body of work released over the last few years and recorded across countries, collaborators and emotional states.

Growth, risk, reinvention are not words artists deploy lightly when their careers have unfolded in public since childhood. Shankar gave her first public solo sitar performance at thirteen, at Siri Fort in New Delhi, accompanied by Zakir Hussain, as part of her father, sitar maestro Ravi Shankar’s 75th birthday celebrations. She had already been accompanying him on tanpura from the age of 10. By her mid-teens, she was touring internationally. By 16, she had signed her first recording contract.

You may also like

Born in London, raised between Delhi, California, and the UK, she is frequently described as British-Indian, Indian-American, or some ungainly combination of all three. She finds the constant correction wearying. “Even on Wikipedia, someone keeps deleting Indian,” she says. “It makes me sad, because I feel Indian and I am. I was never part of the diaspora,” she says. “We came back for several months every year. India was always one of my homes.”

This insistence matters. Her music—its architecture, discipline, improvisational intelligence—comes directly from a deeply embodied relationship with Indian classical tradition. “It’s not just my blood or my body,” she says. “It’s my music. I learned in this traditional way with my father.”

Ravi Shankar looms large over any telling of his daughter’s life—not as one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, but as a figure who reshaped how the West heard Indian classical music. George Harrison, Yehudi Menuhin, Woodstock, the counterculture—his sitar became shorthand for transcendence.

For Anoushka Shankar, that legacy was both a gift and a gravitational force. Her training began at eight, under her father’s disciple Gaurav Mazumdar, but music was already the air she breathed. Her mother, Sukanya Rajan, was a dancer; movement, rhythm and the body’s intelligence were part of her earliest education. Yet, the sitar was not love at first sight. “My first hunger was for the piano,” Shankar admits. “It felt like my baby for a long time.”

Witnessing her father play changed something inside her eventually. “I could see the depth, the journeys they were going on. And as I got more advanced, I could experience it for myself.” Her parents were careful not to frame the sitar as destiny. She was asked to try it—not to inherit it. “They said, ‘If you don’t like it, that’s fine. Just give it a go’.”

You may also like

But while she was becoming a globally recognised classical musician, she was also quietly living a parallel existence. One that did not fit the image of the dutiful torchbearer. “I was rooted in classical music and spirituality,” she says. “But I was always really attracted to the darker side—punk worlds, electronic music.” The contrast was extreme. “I’d be playing Carnegie Hall,” she says, “and then I’d be at a rave in black lipstick in LA two days later.”

At the time, there was no template for this duality. “I was in a vacuum,” she says. “I didn’t know anyone living in both those worlds.”

This tension—between discipline and abandon, devotion and rebellion—would later become the signature of her work. Albums like RISE, Breathing Under Water, Traveller and Land of Gold didn’t dilute the sitar; they expanded its emotional range. Electronic textures, flamenco echoes, cinematic darkness, political urgency—all folded into a sound that refused to choose between purity and possibility.

However, breaking away from purism came at a price. Shankar absorbed criticism that younger artists today are largely spared. Even personal autonomy was framed as transgression.

“I remember being asked when I wanted kids,” she recalls. Her response—mid-twenties—became tabloid fodder. When she added that marriage wasn’t a prerequisite, it was treated as scandal. She wasn’t trying to rebel. “But neither was I towing the line,” she says. “I just had to find room to feel like myself.”

That room existed, crucially, within her family. Ravi Shankar and Sukanya Rajan were renegades in different ways. “My parents had me out of marriage. I was at their wedding when I was seven,” she says. “They were open with me about life. They were okay with who I was. That was enough.”

You may also like

Three decades in, Shankar now sees her career in chapters. The first decade was about being a student—earning legitimacy within classical music. The next was about joining the dots, allowing her broader personality to shape the work. Albums like Breathing Under Water, Traveller, Traces of You and Land of Gold brought collaborators ranging from flamenco singers to electronic producers to M.I.A., without ever abandoning the sitar as a serious instrument.

If there is a through line, it is instinct. “I’ve learned to trust my artistic intuition above everything,” she says.

That instinct guided her through the death of her father in 2012, motherhood, political awakenings and creative block. It also led to her most ambitious project yet: the Chapters trilogy began as a necessity. “I was struggling with personal stuff,” she says. “I didn’t know how to write music from the place I was in.” So, she changed the conditions. Each chapter was recorded in a different country, with different collaborators, over short, intense sessions. “It was about creating something exploratory, safe and intimate.” And each chapter captured a moment rather than a conclusion. “It wasn’t about perfection,” she says. “It was about emotion.”

Only in retrospect did the shape emerge. Forever, For Now explored fleeting beauty amid pain. How Dark It Is Before Dawn widened the lens to the collective—wars, genocide, the sense that survival alone is not enough. “A deeper shift is needed,” she says. “And that requires a real pause.”

We Return to Light arrived as belief rather than resolution. “There’s always another morning, another spring.”

Today, at 43, Shankar has nothing left to prove. Which may be precisely why she keeps moving. “Being an artist’s like being a participant in life,” she says. “There’s always another summit. Another universe.”

To read more stories from Esquire India's January 2026 issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest newspaper stand or bookstore. Or click here to subscribe to the magazine.