The New OceanGate Documentary Dives Deep Into The Depths Of The Man Who Built It

And serves as a mirror to our age of ego-fuelled disruption

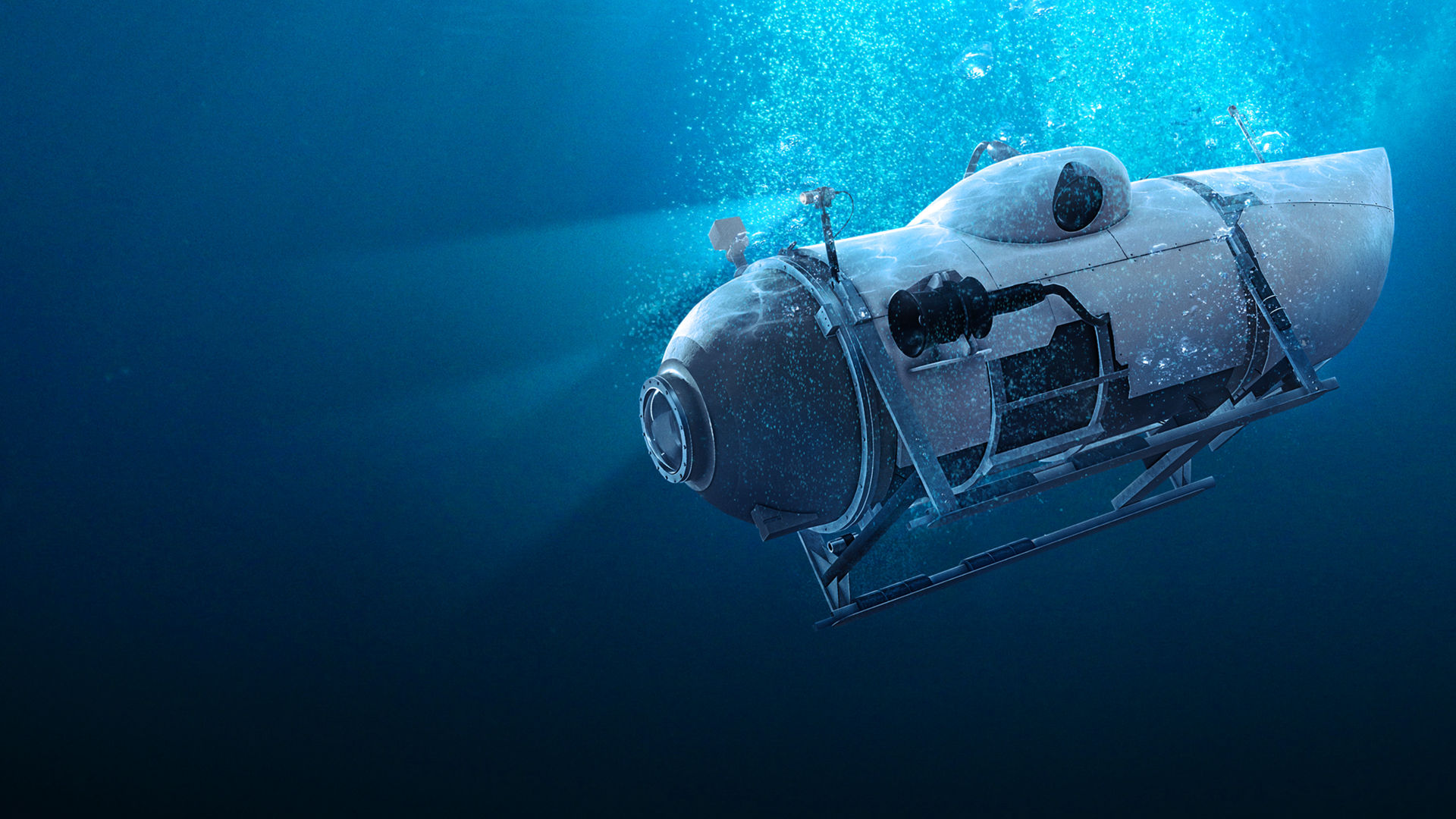

In the summer of 2023, the world collectively held its breath as search efforts zeroed in on a vanishing blip in the North Atlantic: Titan, the deep-sea submersible designed by OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush, had gone silent en route to the wreck of the Titanic. The press did what it does—oxygen countdown clocks, satellite pings, speculative maps. But within days, the uncomfortable truth emerged: there had never been hope. The Titan had imploded roughly 90 minutes into its dive, instantly killing all five people aboard.

The Netflix documentary Titan: The OceanGate Submersible Disaster, released on June 11 worldwide, directed by Mark Monroe and produced by Story Syndicate, doesn’t rehash the media frenzy. It isn’t interested in re-dramatizing the blinking sonar screens or pings from the abyss. Instead, it offers something more disturbing: a clear-eyed character study of Stockton Rush and the belief system he embodied—one where charisma is currency, confidence can substitute for competence, and being called crazy by experts is proof you’re doing something right.

You may also like

A Vessel Built on Denial

Rather than dwelling on the doomed final dive, the film rewinds to 2009, when Rush—an ambitious entrepreneur with a blue-blood pedigree and a fondness for adventure—founded OceanGate. From the outset, the risks were clear.

One of the key revelations in the film is how OceanGate cut costs by using carbon fiber to build Titan’s pressure hull—an unconventional and highly controversial decision. While lighter and cheaper than titanium, carbon fiber had never been proven safe at depths of 3,800 meters. It degrades with use. It fatigues. It cracks. And Rush called those ominous creaking sounds “the carbon fiber seasoning.”

“I’m convinced that the sub could have imploded at any time,” says director Mark Monroe. “It was shocking that it made as many dives as it did.”

The film includes chilling footage of failed pressure tests and emails from early collaborators—including a Boeing engineer—warning that the design had “no safety margin.” Rush ignored them all. “I know what the hell I’m doing,” he says in one meeting.

David Lochridge, the company’s Director of Marine Operations, was one of the first to raise alarm bells. After Rush nearly crashed the sub during a dive to the SS Andrea Doria in 2016, Lochridge wrote a report stating flatly: he had zero confidence in the Titan’s safety.

What followed was a tense HR meeting in which Lochridge—audio of which is played in the film—tells Rush: “The goal for this document is the safety of anybody that goes in there, including you.” To which Rush replies: “I don’t want anybody in this company who is uncomfortable with what we’re doing.”

Lochridge was fired. Then sued. OceanGate sued him for supposedly disclosing confidential information to safety regulators. OSHA, where he filed a whistleblower complaint, never came to a conclusion. The legal pressure forced him to withdraw.

“It felt like I was gut-punched,” Lochridge says in the documentary.

Optics Over Engineering

From the outside, OceanGate looked legitimate. Rush claimed affiliations with Boeing, NASA, and the University of Washington. But as the film shows, these partnerships were nominal at best. In a 2012 email, a Boeing engineer warned: “We think you are at high risk of a significant failure at or before you reach 4,000 meters. We do not think you have any safety margin.

The warnings kept coming. The documentary includes footage from pressure tests where carbon fiber cylinders failed catastrophically. Still, Rush pressed on, taking wealthy adventurers—dubbed “mission specialists” to avoid maritime commercial regulations—down to the Titanic wreck site. Between 2021 and 2022, Titan made 13 successful dives to Titanic depths. The 14th dive was its last.

What’s even more chilling is the implication that the vessel may have already been compromised. According to OceanGate’s own monitoring systems, a 2022 dive suggested structural damage. “The hull was likely delaminating,” Monroe says. “And yet, they kept going.”

Rob McCallum, a submersible expert who once consulted for OceanGate, recalls: “He had every contact in the submersible industry telling him not to do this. But once you start down that path … you have to admit you were wrong. That’s a big pill to swallow.”

You may also like

The Prophet Of The Deep

Two years after the Titan's implosion killed Rush and four paying customers, the documentary offers something more disturbing than the expected engineering autopsy. What emerges is a portrait of American capitalism's most seductive and destructive myth: that confidence, properly weaponized, can substitute for competence, and that being called crazy by experts is the ultimate validation of genius.

Over 111 minutes, we meet engineers, videographers, submersible experts, and former employees who all paint the same portrait: brilliant, yes. Visionary, maybe. But also “arrogant,” “reckless,” “a narcissist,” and, in the words of OceanGate’s former engineering director Tony Nissen, “probably a borderline clinical psychopath.”

One of the more disturbing moments in the documentary comes from Joseph Assi, a videographer hired to document the expeditions. “If there’s a small island in the middle of the ocean, and you’re the only one who can access it,” Assi says, quoting Rush, “then it doesn’t matter who owns it. You have ownership over it.”

That philosophy—access equals ownership—explains a lot. To Rush, being first was more important than being safe. It was about dominion, novelty, legacy. He wasn’t just trying to visit the Titanic; he was trying to write his name into the next chapter of its mythos.

Let’s be honest: Stockton Rush didn’t just build a sub. He built a temple—to himself. And then, in a tragic but deeply on-brand move, he died in it. The documentary doesn’t offer us a fresh tragedy—it offers us a mirror. A window into that very specific, very 21st-century delusion: that tech can solve everything, risk is sexy, and billionaire tourism is the final frontier of masculine conquest.

The Real Horror

The documentary avoids sensationalism and instead offers a clear-eyed postmortem of a preventable disaster. It doesn’t need to show grainy footage of debris or play eerie sonar pings to haunt the viewer. The horror is in the boardrooms, the memos, the ignored emails. It’s in the way Rush leaned into risk while convincing others he had conquered it.

The Titan’s implosion at 3,300 meters came just 500 meters shy of its intended target. But the closer you look, the more it becomes clear: this wasn’t an accident in the traditional sense. It was the result of calculated, conscious decisions. At every critical juncture—whether to test more, to class the sub, to listen to engineers, to stop and reassess—Rush chose to move forward.

There will be more documentaries about Titan. There may be biopics, reenactments, even—god help us—a streaming mini-series. But Titan: The OceanGate Submersible Disaster does something essential: it reminds us that the language of innovation and disruption should not go unchallenged, especially when lives are at stake.

At the end of the documentary, Monroe sums it up plainly: “There are certain rules that do apply, like the rules of physics, the rules of science. These rules do apply to all of us.”

Stockton Rush bet against them. And lost.