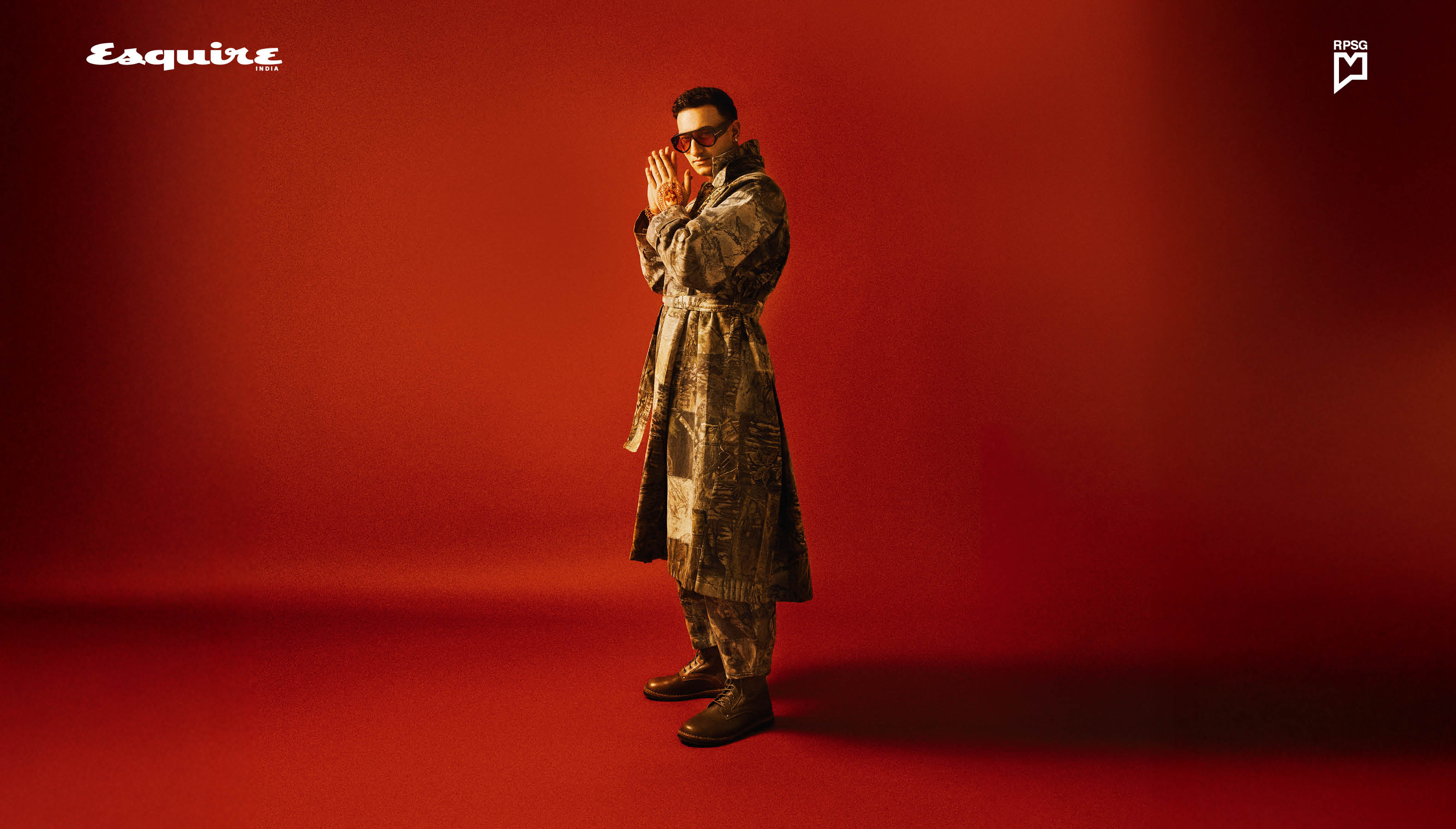

Rishab Rikhiram Sharma Is Tuning Ancient Traditions For New Ears

Hip-hop style chops, genre-blending, soundscape, a mindful approach to both music and mental health

Music surrounds us. Amidst nooks, corners and crannies, emanating from blaring woofers, buzzing bees and lullabying nannies—there’s always a tune playing, a beat brewing, a song folding in, or one that’s lurking right there, waiting to be unfolded. Music, a ubiquitous force that not only uplifts our existence but also documents the political, social, cultural, anthropological and economic crests and troughs of our times, is everywhere.

But like art, language, performance, and other forms of expression, music—its modes and manners—is ever-changing. From vinyl and cassettes to compact discs and digital streams, the way we consume music is a tale of evolving tastes and times.

And like music, its creators—the musicians—evolve too.

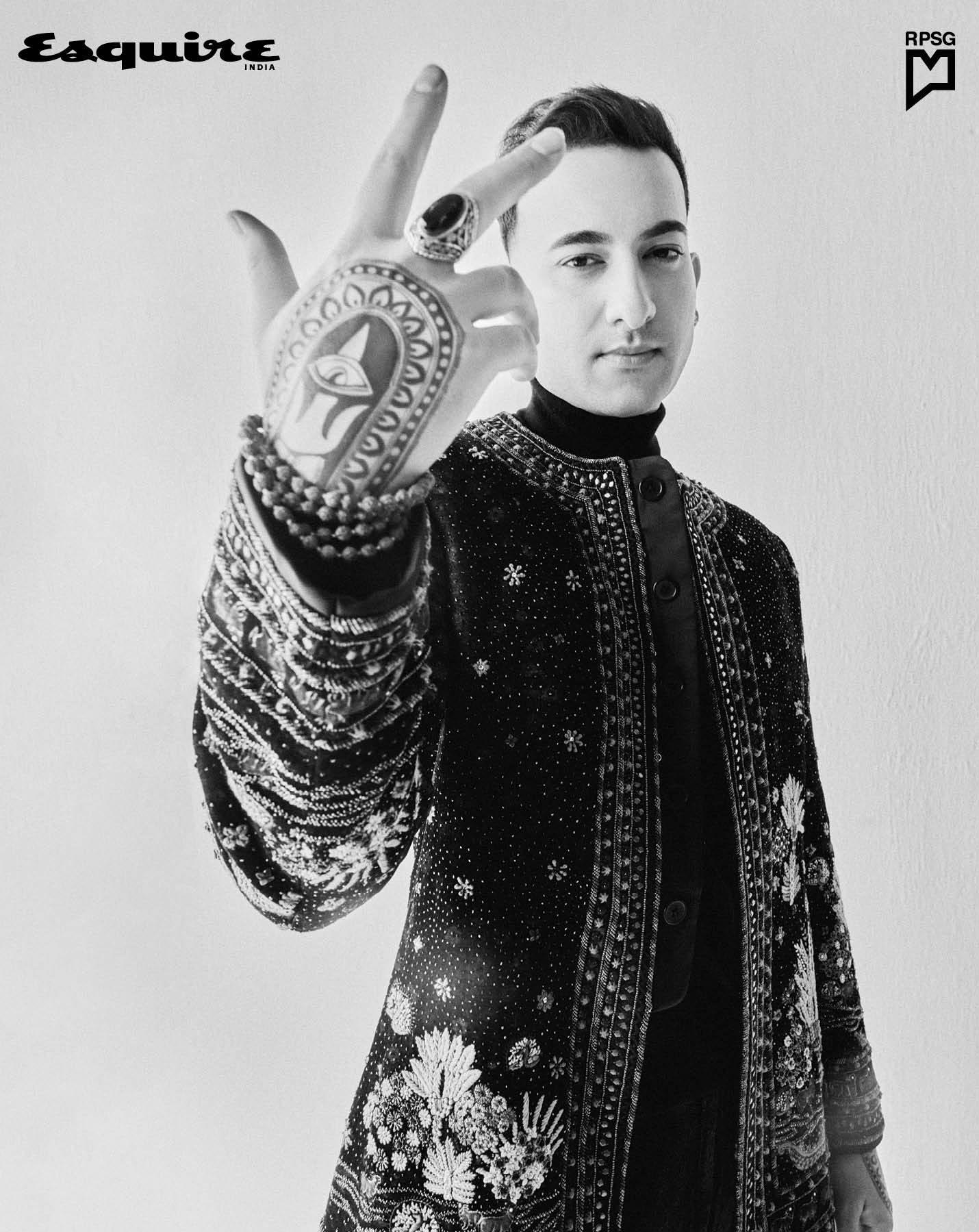

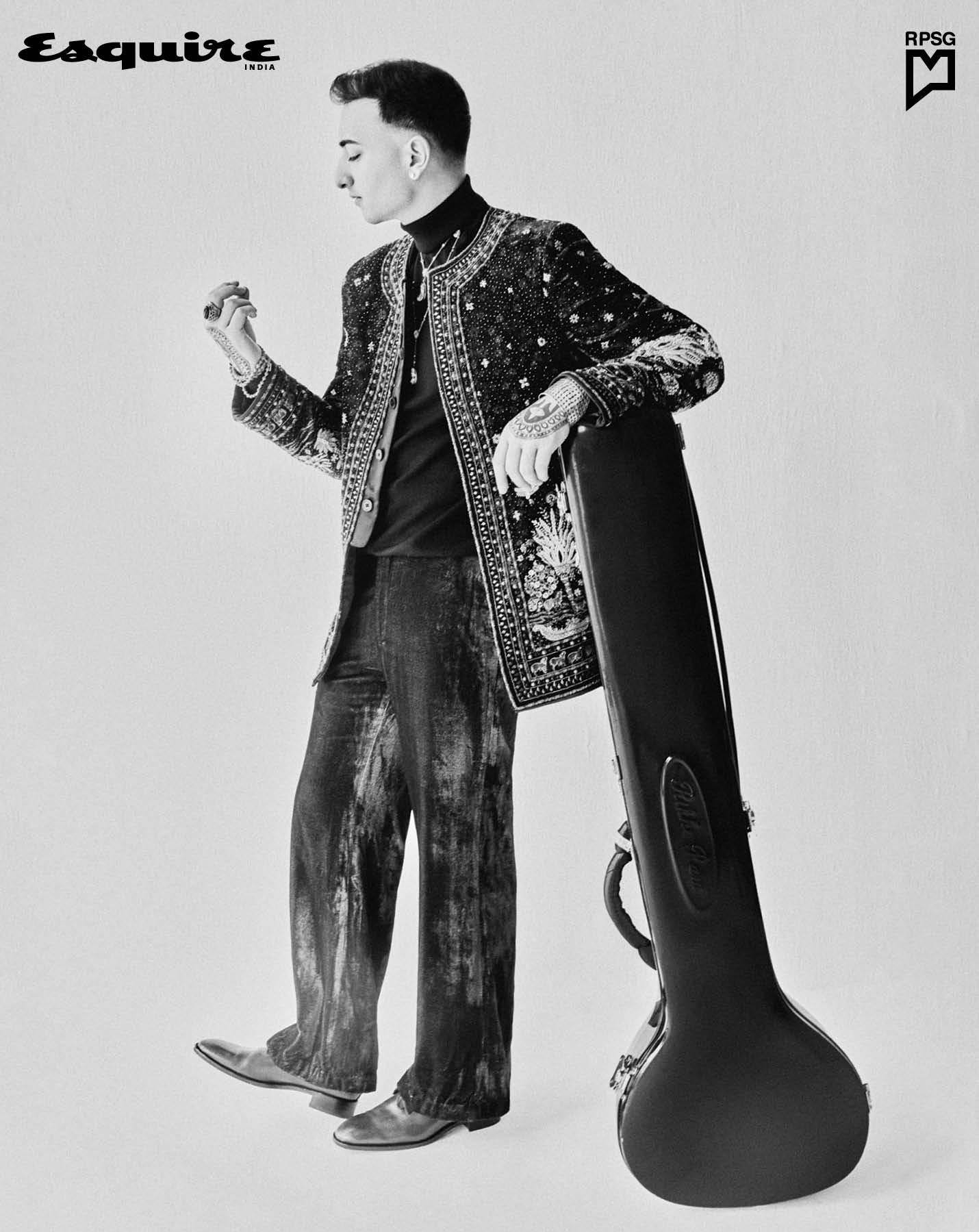

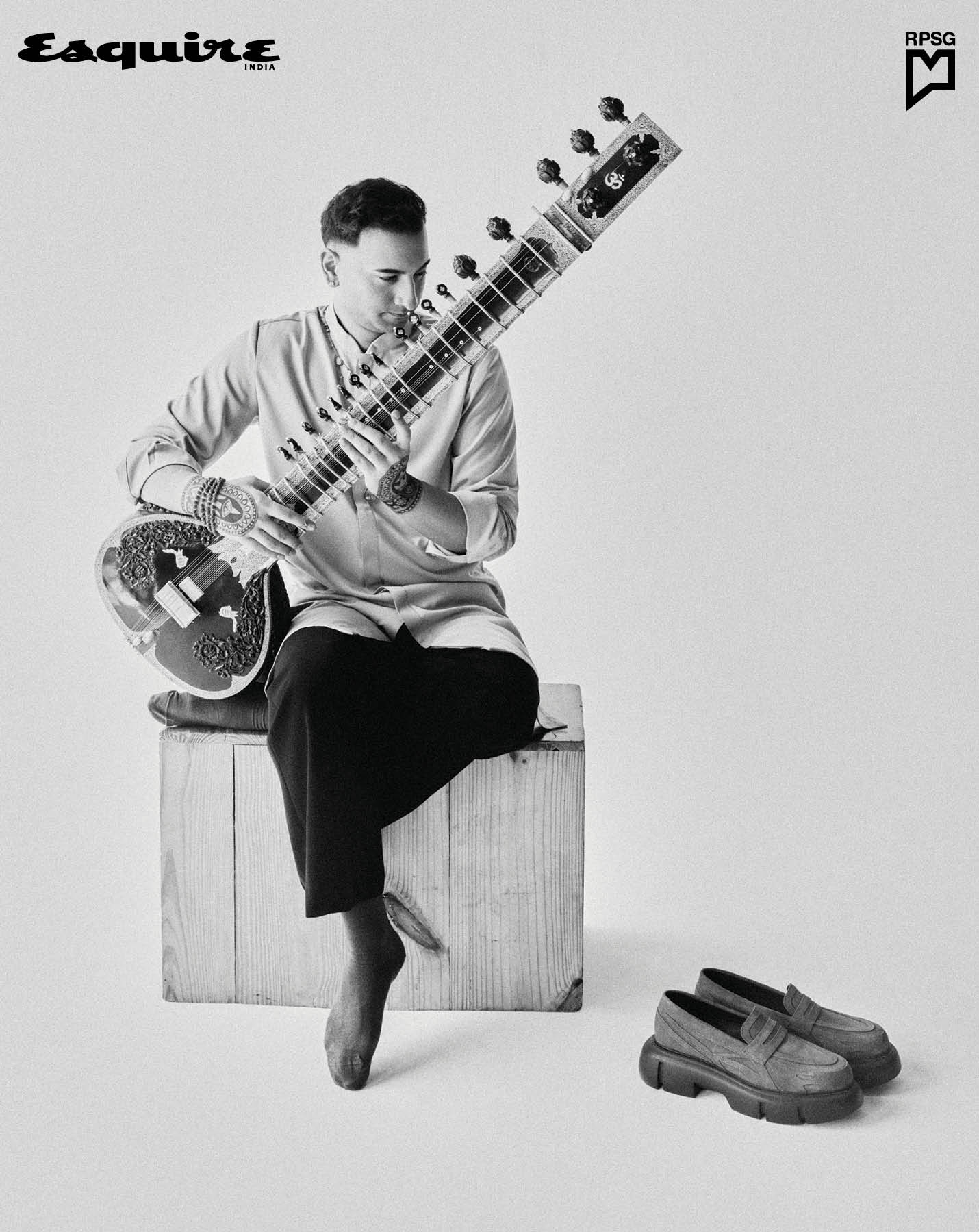

Rishab Rikhiram Sharma strums his sitar with the mizrab (its plectrum), his henna-decorated hands gliding across the strings. He plays an amalgamation of the Harry Potter and Game of Thrones soundtracks, his head moving in a rhythmic synchronisation with the music. The excitement and ecstatic hysteria of the audience is palpable. It’s not something one would expect from a classical musician.

But then, often, memorable moments emerge from the unexpected.

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, the sarod maestro, is said to have played the Bengali anthem Ekla Cholo Re and popular Punjabi folk songs in some concerts, leaving the audiences mesmerised. Ustad Zakir Hussain tapped the tabla (which he referred to often as a brother, or mate) to create the sound of a horse running, all to the audience’s rapture.

When Elvis Presley broke into the scene, no one had seen anything like the ‘hound dog’—the frenzy he sparked is the stuff of legend. Pandit Ravi Shankar’s global collaborations, David Bowie’s manipulations in both his sound and image, and the way Beethoven or Stravinsky broke musical norms all exemplify the impact of the unexpected, and the power of going off the grain. Yes, we’ve mixed up some genres there—but that’s exactly the point.

In India, classical music holds a revered space. Its complex ragas and intricate talas trace back to ancient times and are believed to have transformational powers—folklore even attributes some ragas with the ability to cause rain, fire or seismic shifts. Often there’s a deliberate, slow pace of performance, aiming to create a bridge between our internal emotions and the external world.

There’s a meditative quality associative with the music, and the players of these notes, the musicians, are like sound alchemists and spiritual seekers. The ragas they play are like formulas, believed to align with the universe’s higher frequencies when mastered. It’s a venerated space, heavy as much with the weight of the instruments, as with the philosophies they uphold.

But this weight can feel stifling—especially in today’s hyperconnected world of cyber natives, climate anxiety, financial flux, sensory overload and viral everything. This weight can bog down a musician, especially in today’s hyperconnected world. Not our man here though.

At 27, Rishab understands the complexities and challenges that come with playing an instrument that carries with it the legacy of time and tradition. But he is also unfettered in his vision to showcase the enlightening (and entertaining) power and prowess of this music to the world.

And he is determined to brave it all.

Whether he’s playing the notes of Raag Bihag or riffing the tune of a Hindi film song, his performances brim with not just intensity, but also a joyous and adventurous abandon. Gaining audiences across the world, he is unafraid to mix modern sounds and techniques with traditional notes and have fun while at it. His talent and dedication seem set to breathe new life into traditional music.

In an Esquire India exclusive, Sharma talks about the importance of traditional music in today’s time, along with giving an insight into his life and learnings, dreams and dares.

What were the biggest challenges you faced when starting out?

Losing Guruji (Pandit Ravi Shankar), my mentor and musical inspiration, within two years of being under his tutelage. I had lost my hero and felt so lost myself. I was the youngest and am grateful to his senior disciples for taking me under their wing. Apparently, Guruji had conveyed to them the syllabus that I was supposed to learn and that they were supposed to teach me, so in the end, it sort of worked out.

The other challenge was getting accepted in the classical music space. Since I come from a family of musical instrument makers, I’d be told —‘You know, you are a good sitar player, but you should stick to making instruments.’ I think that sentiment also came from the space of preservation and continuance of tradition, as the art of making instruments and my family’s legacy in that needs to continue as well.

However, I always thought that they don't have to be mutually exclusive. Why can't I do both? So yeah, I never listened to them and both are continuing.

How did you find your unique sound or style?

Well, it’s been a journey. The first few years, I was copying Guruji—whatever he taught me, whatever he was playing, I would simply, exactly emulate him. However, Guruji always said, “Don't copy me, rather think like me, understand my thought process”. I have adapted and incorporated that into my music.

Interestingly, at the same time I was also into a lot of EDM—electronic dance music. Pursuing EDM with my sitar practice in the initial days has a lot to do with the music I make today. Consequently, I started experimenting with various sounds and understanding diverse genres—underground, hip-hop, pop, melodic and mumble rap, various techno styles. Using these musical explorations, while in college I made Kautilya, Chanakya, Roslyn, Tilak Kamod and most of the initial tracks.

Along the way, another wonderful and unique way to look at music emerged for me from the space of deep personal experiences. I realised how the sounds of the sitar, and our traditional music helped me pull through tough situations and heal from losses incurred in life. I wanted to share that with the world. And so came into being the ‘Sitar for Mental Health’ initiative. It helped me cope with depression when I lost my grandfather. And I am amazed to see how many people have connected and continue connecting to this unique approach.

Tell us about your creative process: How do you start composing a new track or an album?

You know, my process is often quite impulse-driven. It usually starts with a melody, or sometimes with just a drumbeat and then I just go with the flow. At times I write the whole song within a night, or at least like a demo or a draft and then I improvise and polish it wherever I can. That’s how I’ve composed my next release, the working title is Temple Burn, or perhaps I’ll call it Burning Heart—am still finalising the name. But I can say one thing—the next song is going to be amazing.

Classical music needs patience and a certain samarpan (assignation)—both for the performer to create as well as the listener to cherish it. In a world that’s so fast-paced—how do you see people connect to classical music?

In a way the answer lurks in the question itself. The lives we lead today are stressful, filled with anxiety and immense tension. And that’s where music acts as a boon and a balm. I see a lot of people today, across various age groups, connect to classical music—or rather ‘traditional' music as I prefer to call it—for soothing their anxieties and imparting peace of mind. I call it traditional music because it’s pulsating, evolving, ever-changing and alive.

And talking about samarpan—yes, one has to surrender as a listener too. Which is why when we do our shows, we ask people to leave every thought behind and just come in with a fresh mind. To sit down with closed eyes, focus on the breathing, meditate and then soak it in note by note. And then when they experience it like that, they can feel the positive impact on their mental health. That's the feedback we have received from not only our listeners, but also the psychologists and professionals who work in the mental health space.

Your guru, Pandit Ravi Shankar, transcended the traditional boundaries of classical music. His collaborations with George Harrison, Philip Glass and Yehudi Menuhin played a key role in fostering Western appreciation of the form. Yet, in classical music and dance, even the slightest rebellion or deviation from the syllabus is often frowned upon. What’s your take?

Yes, Guruji got a lot of criticism as well—especially for mixing Western and Indian classical music. But the fact that he collaborated with so many global artists also opened the doors for new soundscapes to develop. I'm going to go ahead and say that if Guruji hadn’t done that, many contemporary sounds, experimental progressive music, and even the modern Bollywood music, wouldn't have existed.

Whether you hate it or love it, I think such collaborations are very important. That's the only way our music will survive, evolve and reach wider horizons. I mean, when Guruji collaborated with George Harrison and The Beatles came to India, they actually bought sitars from my grandfather. They also purchased tanpuras, tablas and many other Indian instruments. The focus on our music and culture grew immensely. How’s that bad? New ideas are always critiqued initially, but then their greatness and impact are felt later on. A lot of people criticise me as well.

The fact that I experiment, fuse various genres or play many diverse tracks on the sitar isn't always looked upon generously, but I am serving a bigger vision today. I believe we have to make these instruments, and the magic of their sounds, more accessible. I don't want to be the fastest sitarist on this planet. I want to be the slowest sitarist on this planet. I want people to heal, to calm down and just enjoy the beauty of this music breath by breath, note by note. I've been doing this for the past five years. This was our biggest year, and I feel it’s going to grow from here on.

Do you have any rituals before you go on stage?

I don't have any pre-performance rituals per se because most of the time I’m running late (laughs). But yes, styling checks are of course looked into. Then I just get my head in the zone—like, I’m gonna kill it tonight.

If it’s an intense theme, or a spiritual rendition, then I like to meditate for a bit before the show.

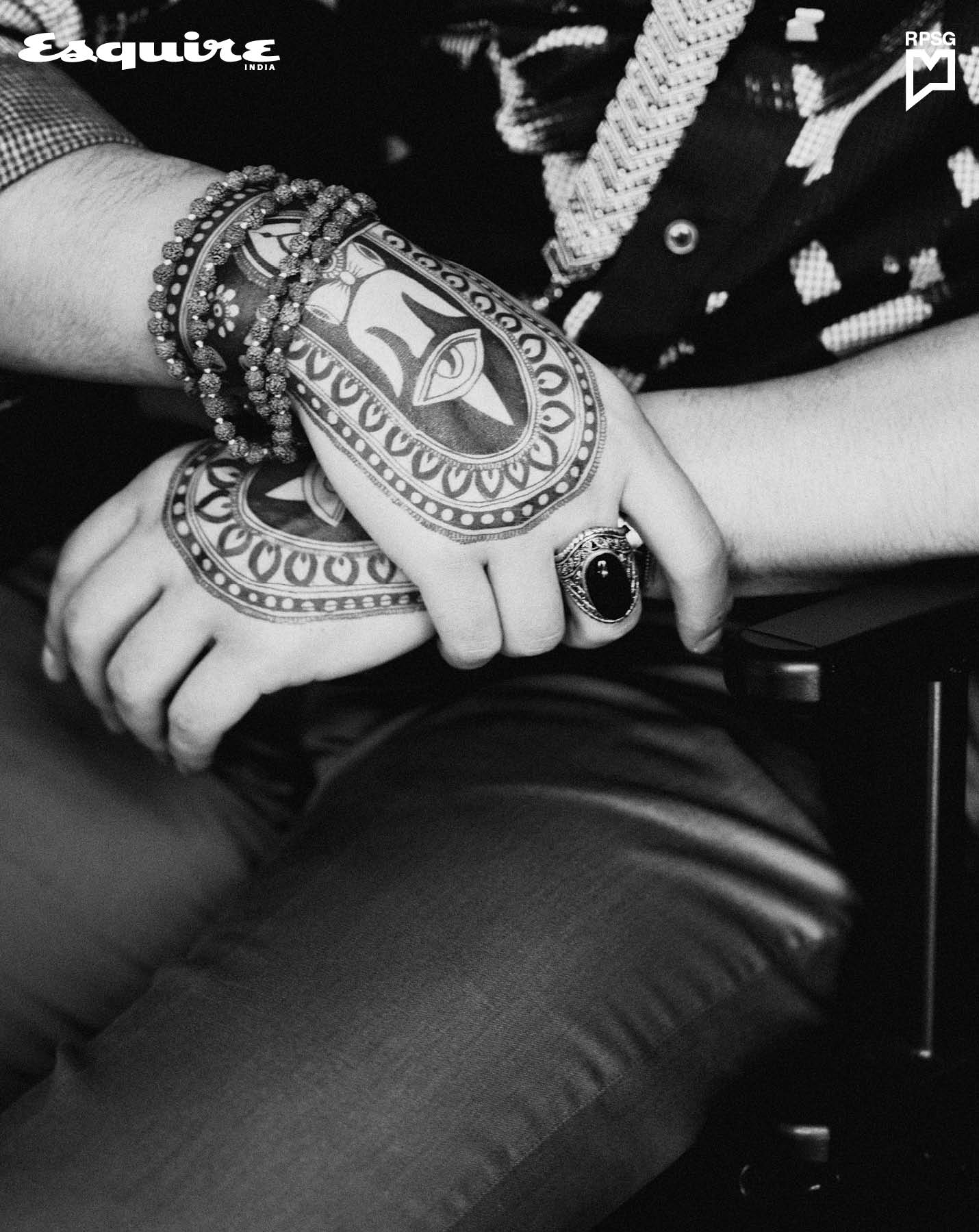

Now that you mention styling checks, let’s talk about style. You’ve spoken about breaking stereotypes and challenging sartorial gender cliches in context of the henna you sport on your hands. You also experiment with hairstyles and have a proclivity towards jewellery and experimental clothing. Were you inherently inclined towards fashion, or have you developed your sense of style through an evolutionary journey?

As an artist and a performer, I always think of how I can elevate the listener’s as well as the viewer’s experience. For the listener, I experiment with sounds. For the viewer, it’s the visual. And that has led me to think of ways to decorate myself. There’s a lot of focus on my hands when I play. Initially, I didn't have the money to explore jewellery. Moreover, rings, or gloves are a hindrance when playing music. I thought of tattoos too, but their permanence coupled with my aversion to needles put me off the idea.

And that’s when I took to henna or mehendi—the natural dye. It isn't permanent and gives me the ability to tweak the design and tone for various shows. Besides, it’s great for the skin, and of course—looks dope. I also thought—why do girls have all the fun? Why can’t we make it cool in a way that the boys can rock it too. So, henna became mainstay. So did my diamond ear studs. I’ve also had diamonds in my teeth. I like the rap and hip-hop vibe they lend to the look. And astrologically speaking, they enhance your Venus I hear, as my parents keep telling me.

So, you see, any choice I make when it comes to style is mostly based on need, my instinct, and how it makes me feel. If you feel you look good, you feel good, and if you feel good, your performance is good. Simple.

In a world of electronic music, how does the sound of the sitar hold fort and forge its path ahead?

Oh brilliantly! You know I’ve played the guitar as well. And I can say from that point of view as well, that the sitar can do whatever a guitar can do at this point. The sitar produces what can be called a ‘natural reverb’ or buzz. We can play crazy leads as well as do a lot of bending on the sitar. I believe there’s immense scope. Sadly, many people just use the sitar like an exotic prop in their songs. I try to run away from that.

What’s your biggest dream as a musician?

As a sitarist, I have a very big dream. I want to play for each and every soul on this planet. I want them to experience it once and then it would be up to them to decide if they want to hear it again or not. But I want to expose them to the sound of the sitar at least once.

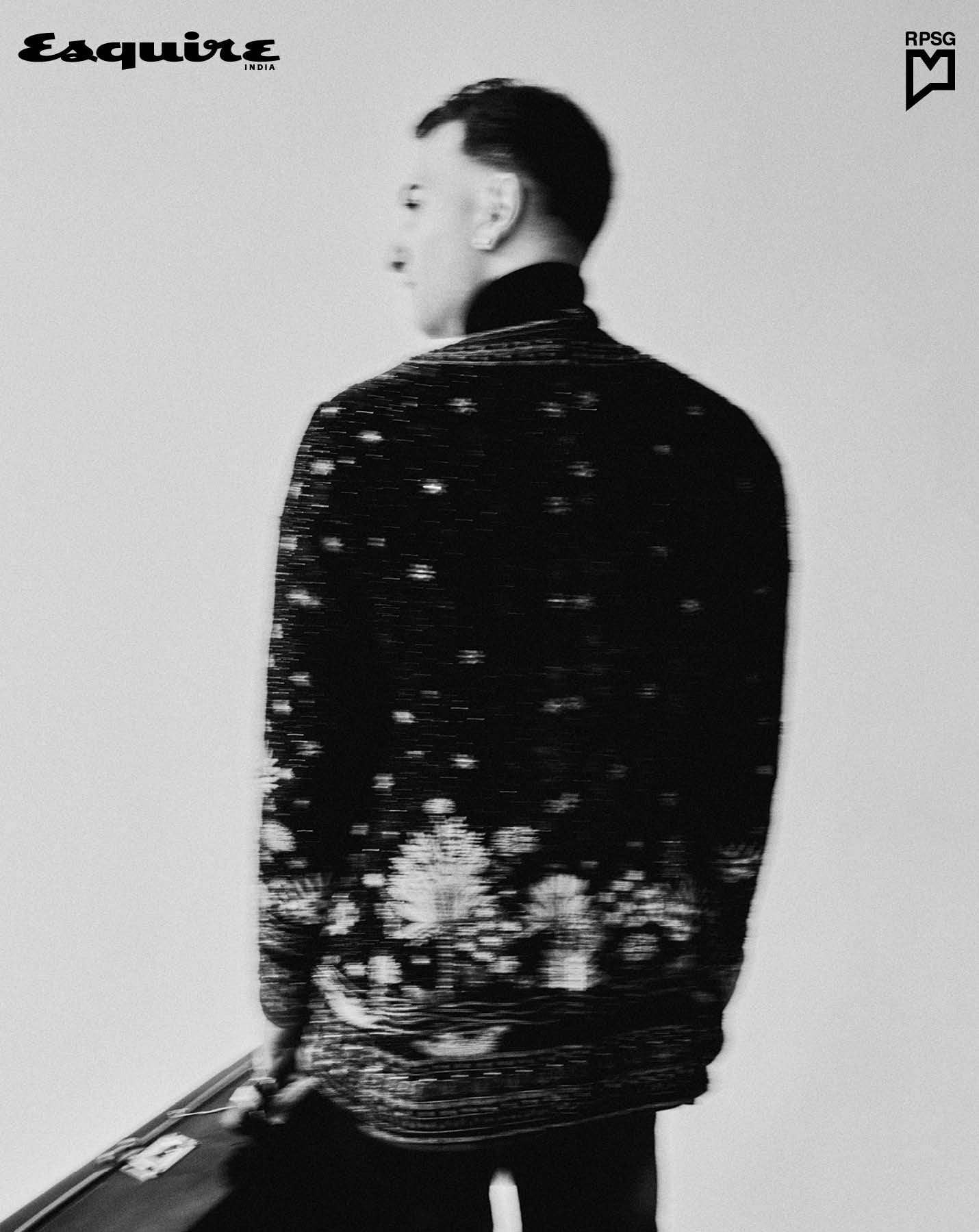

Styling and Creative Direction: Vijendra Bhardwaj

Photographs: Charudutt Chitrak

Chief Assistant Stylist: Mehak Khanna

Grooming: Vishal Sharma (Affinity Salon)

Bookings Editor: Varun Shah

Production: VG Creatives

Artist Reputation Management: Communique PR

To read more stories from Esquire India's May-June 2025 issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest newspaper stand or bookstore. Or click here to subscribe to the magazine.