Whatever Happened To The Great Dosti Yaari Film?

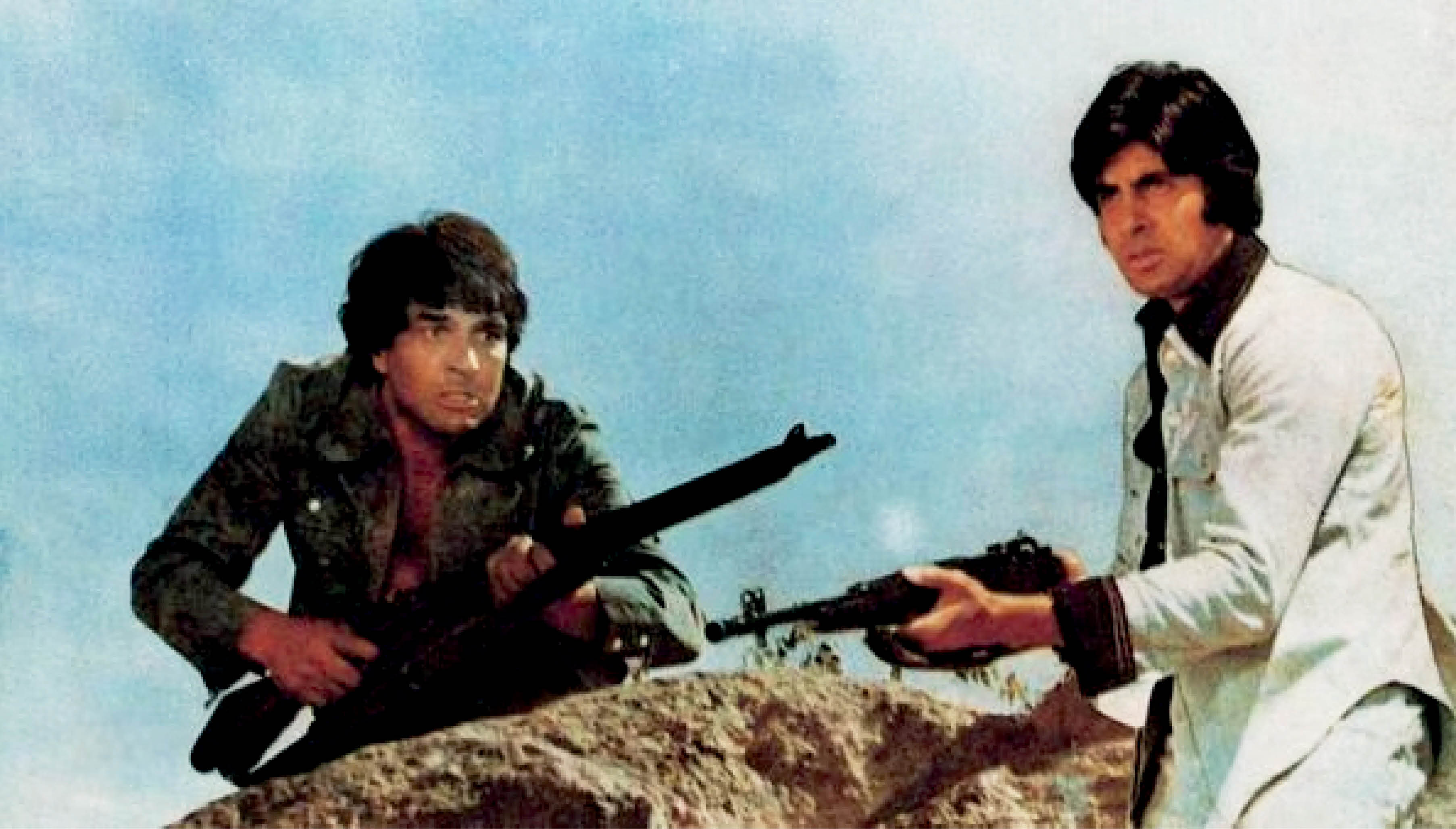

It’s been 50 years since Sholay first blazed across screens, and the legend only grows. But the kind of cinema it came from, the slow-burning, big-hearted bromance, feels like a relic now

TWO MEN ARE GETTING MARRIED, ARCING THEIR WAY AROUND THE SACRED FIRE, performing the saat phere or the seven ritual circumambulations, signifying their union across seven births. The song they are singing is “Yeh Dosti Hum Nahin Todenge” from Sholay (1975)—this friendship we shall never sever.

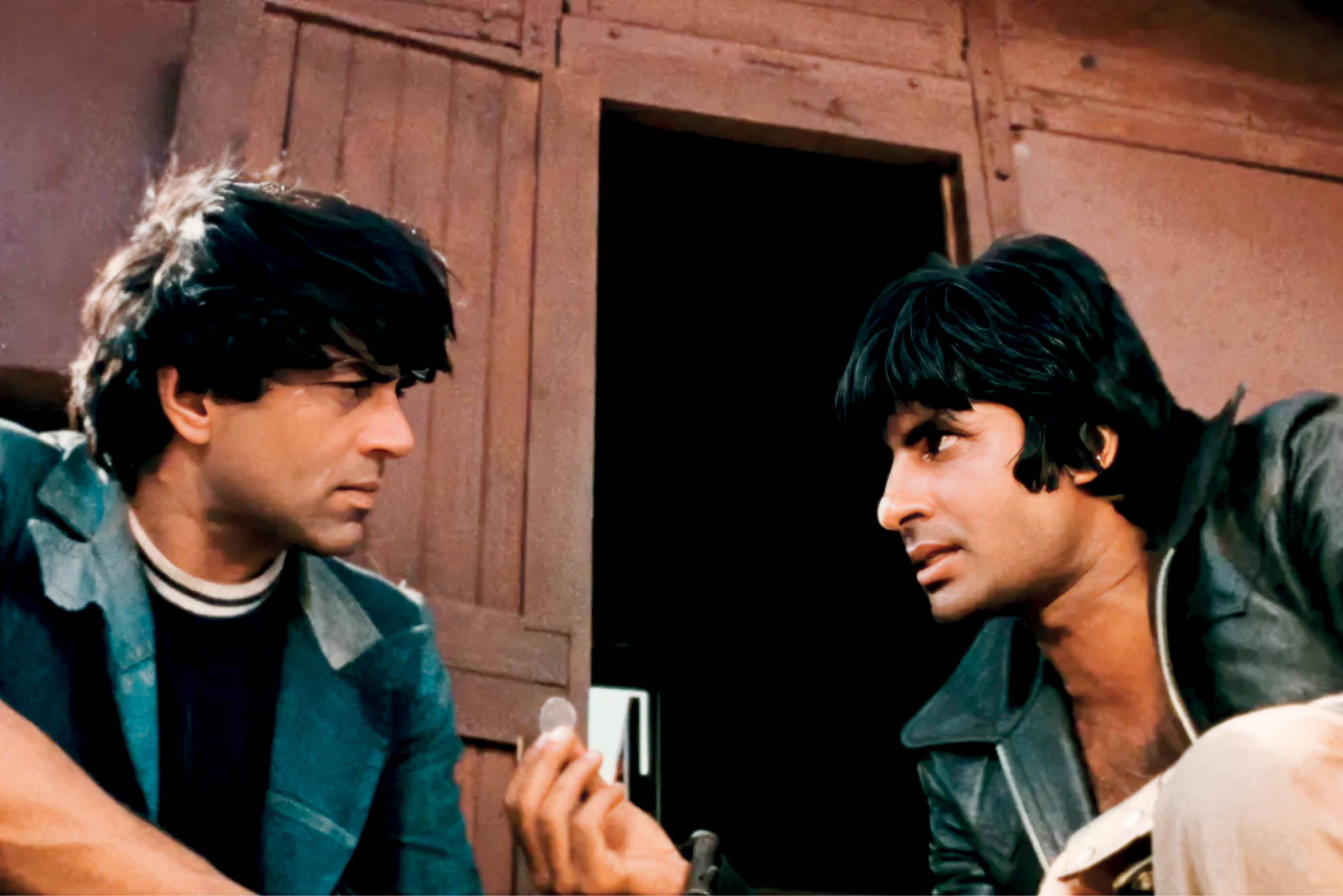

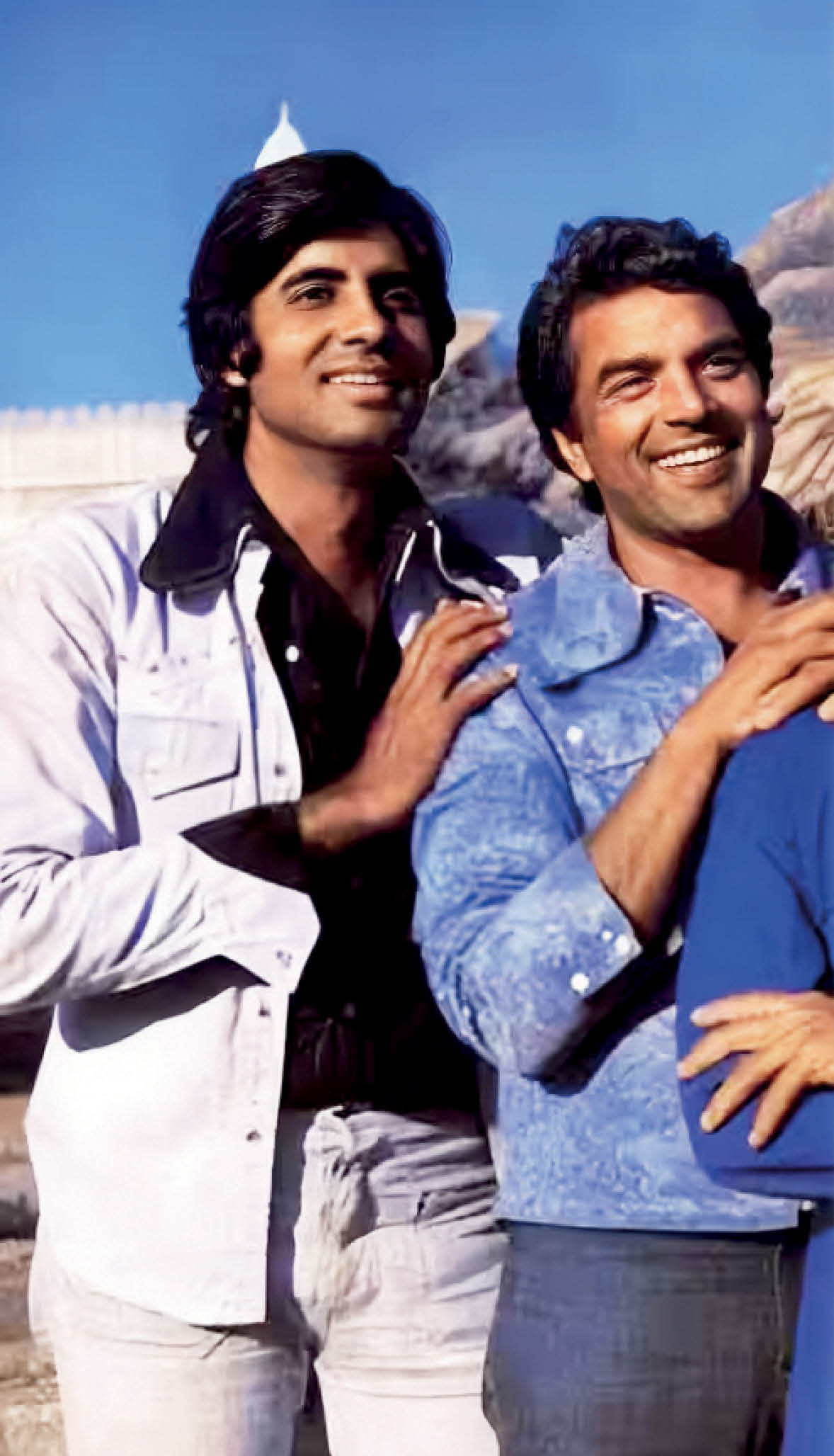

That this image of gay marriage from Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2020)—one of the first such images of homosexual marriage in Indian cinema—is overlaid by Sholay’s dosti or friendship between two denim-clad nomadic outlaws, Veeru (Dharmendra) and Jai (Amitabh Bachchan), shouldn’t come as a surprise. In a cinema deprived of queer representation, and a culture deprived of queer rights, homosexuality is forcefully read into the afterlife of homosocial cinema. Pride parades in the diaspora have re-imagined this song as one of gay love, as have forceful, queer-pilled re-interpretations of the film itself.

You may also like

The other way to look at a moment like this is that the idea that friendship, in all its intensity, can be just as central, just as all-consuming, as romantic love. Here, friendship is just as central to the lives being lived as erotic love; that these moments expand the gamut of homosocial male friendship, and not necessarily that of homosexual love.

It is true that the language around friendship has allowed this erotic ambiguity to bubble up. Dost, or “yaar”—what Veeru calls Jai—a word that emerges from the Sanskrit ‘jaara’ used to describe an adulterous lover, is deployed later in 18th and 19th century Urdu poetry to describe the beloved, blurring boundaries between friend and paramour, comrade and companion, homosocial and homosexual. Cinema has merely borrowed language’s slippery connotation, what Professor Ruth Vanita calls “erotic without being overtly [...] sexual”

It is the ambiguity that is productive, that diaphanous translucence of the word—all the possibilities it can afford, can produce, can retreat from. The song’s lyrics reframe friendship as another kind of lifelong companionship— marriage at an angle.

“Logon ko aate hain do nazar

hum magar, dekho do nahin...

Khaana-peena saath hai, marna-jeena saath

hai, saari zindagi”

''Though two bodies, see carefully, we are one

We shall wine and dine together

We shall live and die together”

This is not to suggest that Jai and Veeru are gay, but to suggest that deep friendship between two on-screen bodies leeches the prospect of any other kind of greater heterosexual romance, for no other love, no other kind of love can surpass this. Re-phrasing the poet and essayist Hoshang Merchant who writes of such films and their latent homosexuality, the female presence is there to only lessen the homosocial sting.

You may also like

On the other hand, when people listen to these lyrics and are only able to imagine marriage, it exposes the limitation of an imagination where the only kind of tether that survives a lifetime is the marital knot. Is this an imagination that forces an idea into a past image? Or one that yearns for such ideas in present images, in present cinema?

It has been 50 years since Sholay’s release, and much of the film’s myth and attached nostalgia point to a kind of cinema we can no longer secrete. It might be worth asking why the dosti-yaari film has withered?

Dinah Holtzman in her essay Between Yaars: The Queering of Dosti in Contemporary Bollywood Films writes, “For the angry young man of the 1970s, dosti is an attractive alternative to marriage since his business revolves around a homosocial network of gangsters.” Does the attractiveness of the dost fade when the economic preoccupations of the protagonist, and the demands of gender representation on screen, shift with the decades?

IN THE 1990S, WHEN THE ECONOMY opened up, when Hindi cinema got “Industry” status flushing in formal finance, and the kinds of movies we made shifted their priorities towards a diaspora with economic and cultural remittance, we got films like Dil Chahta Hai (2001), 3 Idiots (2009), Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (2011), and Kai Po Che (2013), with characters largely clued into global markets and urban metrosexual ambitions. What is also interesting in these films, is that the friendship gets triangulated, three men tangled in a web of urban nostalgia and upper class resentment, where part of this friendship also meant travelling elsewhere, not as lawless vagabonds, but as law-strung tourists.

When we did get stories of two male friends—Kal Ho Na Ho (2003), Munna Bhai MBBS (2003), Gunday (2014) or War (2019) for example—the spotlight was skewed towards one of the two friends. The other is shaded, not by the yaar, but the side-kick. Which is why when films like Sonu Ke Titu Ki Sweety (2018) get made, two male friends—punctured by the presence of one vamp—come across as lovers, longing for each other’s company. The film’s clinching song is ‘Tera Yaar Hoon Main’. Yaar—that word again. Such films rewrite masculinity, softening its demands on each other, by hardening those on women. Then, there are the structural constraints of cinema itself that have changed since Sholay. That Jai-Veeru exemplified a cultural-economic system that allowed for two heavy-weight actors to play friends of equal narrative heft, the same system that produced Sangam (1964), Anand (1971), and Andaz Apna Apna (1994). In these friendships, three was a crowd.

EVEN SOFTER, SMALLER FILMS LIKE DOSTI (1964) traced the companionship between a blind Mohan (Sudhir Kumar) and a crippled Ramu (Sushil Kumar) as they hold onto each other and walk through the world, imbued with a longing that we can only see today, starved of friendship flicks, as romantic. When Ramu disappears, Mohan sleeps with his hand resting on the pillow next to his, hoping Ramu will emerge— an image of utmost tenderness and yearning.

Besides, the two-friend story comes from an era where the writer-director figure was also a galvanising force in cinema, be it writers Salim-Javed or directors Rajkumar Santoshi (Andaz Apna Apna, 1994) or Yash Chopra (Deewaar, 1975) or Rakesh Roshan (Karan Arjun, 1995) who could bring two stars of equal wattage to the same field on their terms. But as we moved towards the star-actor as the sole mobilising voice of a film, the blockbuster’s centre of gravity shifted. Only a director like SS Rajamouli was able to bring two Telugu stars and their warring fandoms into the same film’s celebration with RRR (2022).

With Tiger VS Pathaan being scrapped, questions of a Karan Arjun for the newer generation on the back burner, the only way for men of equal weight to share space is to be on either side of the moral question, as heroes and villains, not friends. For friendship, we have the thruple.

Above are possible stabs at the causes for the disappearance of the dosti film. What about the effect? When you twist and pull a limb of devotion into a triangle, that devotion disaggregates and diffuses.

The dosti film has always been destabilised by female presence, because it is friendship that is the central emotive force. In the triangulated, disaggregated dosti films, it is the self that becomes central—and friendship is something they use to get over their fears, to grow, self-realise, and ultimately settle into heterosexual love. When the skin of friendship gets stretched among more male friends, the choice is not between the male friend and the female lover, but the self and the self-undone.

The idea that friendship is a platonic affection is itself questioned by a new generation who are trying to find in friendship the destiny previous generations sought in romance. Queering friendship, for example, is a project that aims to make friendship—not marriage—the central organising principle of life.

While our theories of friendship have evolved into this, our cinema has turned its back to it, caught in the tangles of the three Ms—marriage, market, military. Thick, all consuming homosociality, which falls into neither category, has withered.

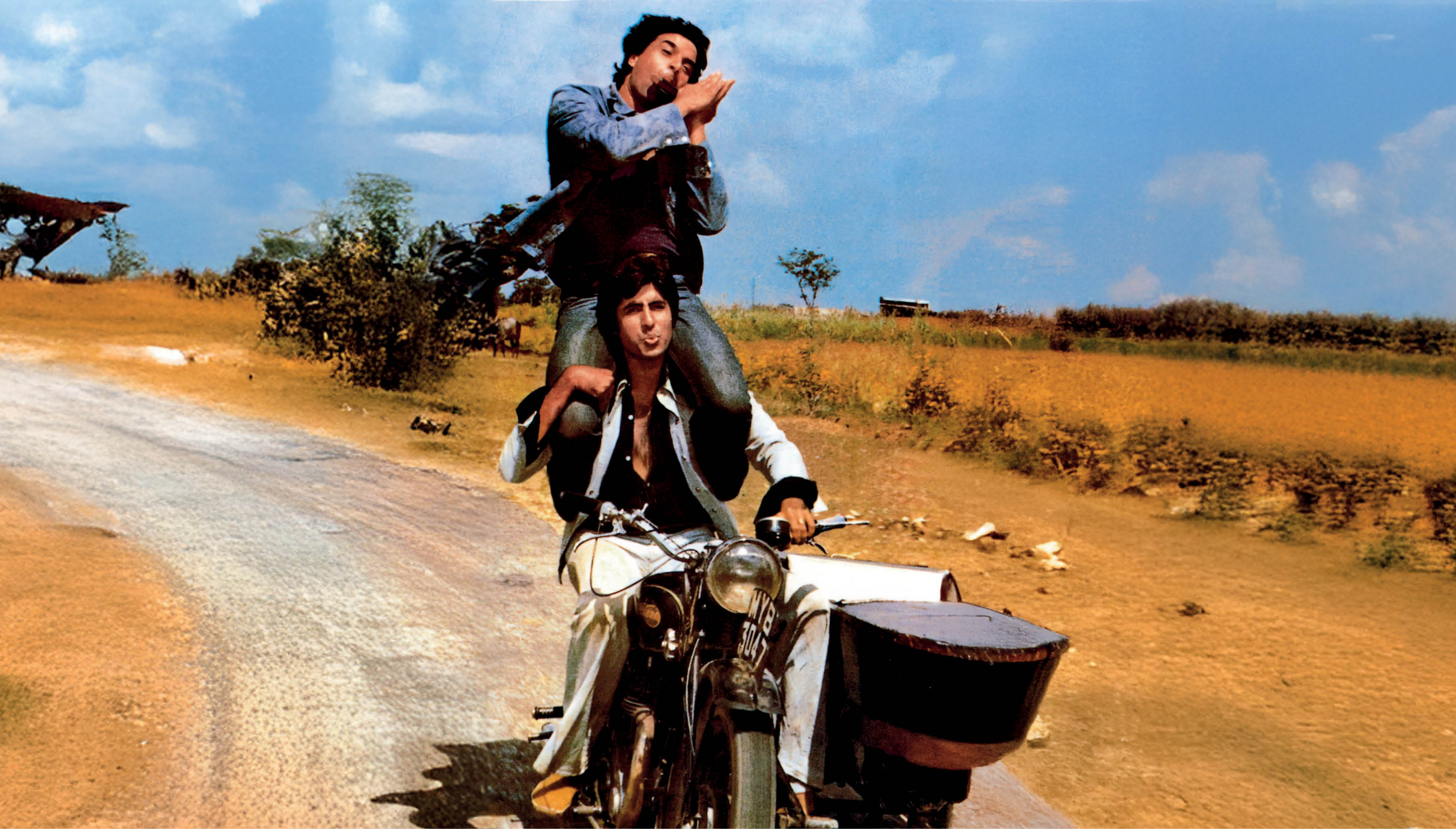

When Veeru’s sidecar dislodges from Jai’s bike in ‘Yeh Dosti’, a parting, and Jai looks anxiously, Veeru emerges from behind Jai, holding him, contorting over his body, sitting on his shoulder, above, behind, beside. It is a coming together that is so comfortable, uninterested in being interpreted and pinned down, lubricated by a desire to merely be in the other’s presence.

The central tragedy of the film is Jai dying in Veeru’s arm—no woman could assume that figure in whose arms to end one’s life, for no yearning is felt within the film that is as strong, no desire so powerful, no pull so tangled in the web of love.

You may also like

To read more stories from Esquire India's August 2025 issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest newspaper stand or bookstore. Or click here to subscribe to the magazine.