An unmistakable nod to the statuesque Taj Mahal, you might assume the 5 times Grammy winner and blues legend, Taj Mahal’s bond with India is a simple ode to the ethereal monument in Agra. But his bond with India isn’t just skin deep. It has risen from a dream and is much more embedded in culture and spirituality.

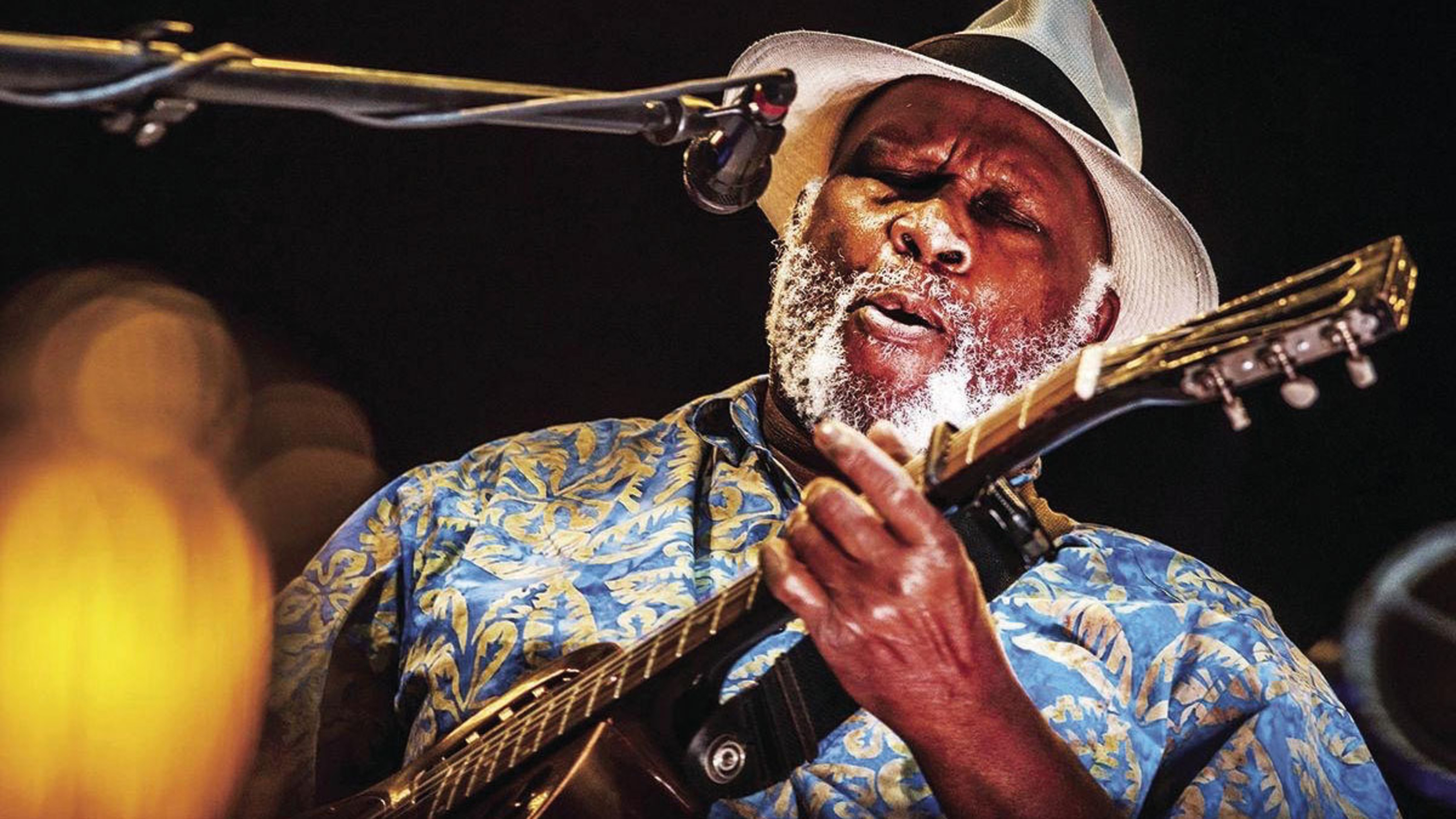

With a career span of over 50 albums, Henry St. Clair Fredericks Jr., who goes by the stage moniker Taj Mahal, won the Best Traditional Blues Album Grammy Award 2025 for Swingin’ Live at Church in Tulsa with his band The Taj Mahal Sextet.

Primarily rooted in traditional country blues, over the years Taj has infused reggae, Caribbean, gospel, jazz, and Hawaiian slack-key influences in his music.

The rawness in his voice gives earthy depths to his songs on his latest album recorded live. The Swingin' Sextet includes his long-time bassist Bill Rich, drummer Kester Smith, and guitarist and Hawaiian lap steel player Bobby Ingani.

Also, the musical nomad was honoured with the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Recording Academy this year.

So, what is the hidden connection with India?

Fredericks became Taj Mahal one day in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the 1960s after something visited him in his sleep.

It was Mahatma Gandhi.

The dream wasn’t one of those abstract visions. In fact, the dream spoke to him of survival and resistance. It shaped his approach to music by turning struggles into a bridge between cultures—the Africa, the Caribbean, the American South, and India.

Taj often heard stories from his parents about India along with his Afro-Caribbean heritage.

And as a child, he would wrap himself in a white sheet on Saturday mornings and walk around the house for fun. A look-alike of Mahatma Gandhi, his mother would say.

In the Taj Mahal: Autobiography of a Bluesman (2001), co-author Stephen Foer describes the chosen stage name as a reflection of “the positive forces in the world” that Taj chose to identify with.

Raised by a father who was a jazz pianist and arranger and having performed with Vishwa Mohan Bhatt and N. Ravikiran in the 90s, the musical nomad grew up ‘intoxicated” by the sounds of Indian classical instruments like tabla, sitar, veena, and tanpura.

Perhaps one of the many reasons why, even at 82, he is weaving sonic threads that go beyond the normal limits of blues.

So now, for a country that loves a good ‘western artist love India” story (Beatles in Rishikesh or India’s Jiju Nick Jonas), it’s surprising that we haven’t embraced the legendary Taj Mahal as one of our own!