Emerald Fennell's "Wuthering Heights" Is A Pure Ragebait

Spoilers ahead for a novel that’s from the 19th century and has been adapted widely before

Director Emerald Fennell’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights has arrived in theatres, and it might just be the horniest expressionistic take yet on Emily Brontë’s untamable classic. But how much of the film is faithful to its source material—or is that even a question we must ask anymore?

Unlike the dark, haunting mood of the literary original, Fennell’s film opens with two children, Catherine (played by Charlotte Mellington) and Nelly, watching a public hanging. As the hanging man gasps grow louder and leads to his end, the film establishes its blunt thesis with shocking provocation: the dead man becomes erect, and the spectacle in turn arouses those witnessing the execution. It is an aggressively unsubtle opening for a story long associated with repression, atmosphere, and psychological rot.

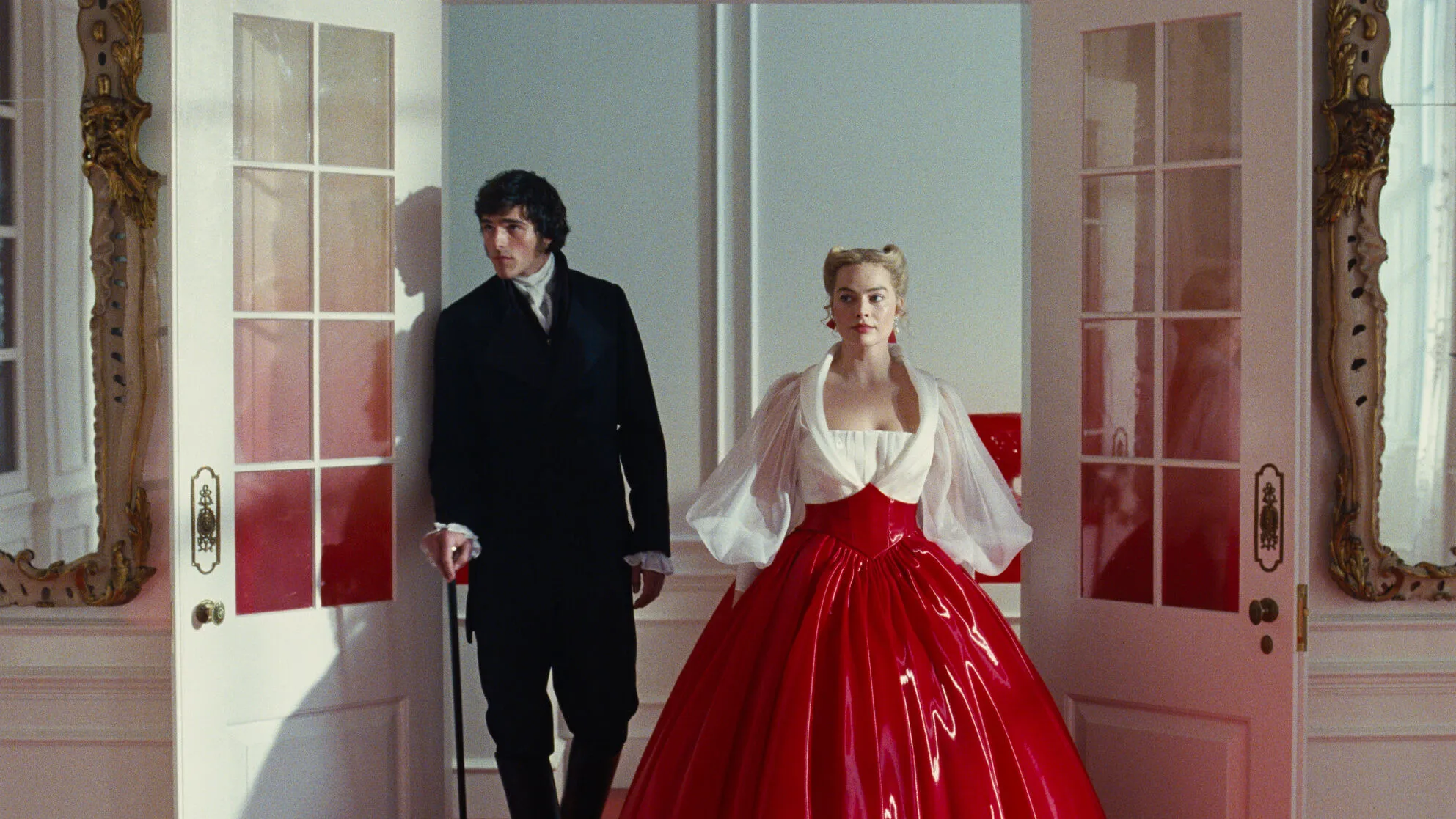

Starring Margot Robbie as Catherine Earnshaw and Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff, Fennell’s "Wuthering Heights " conveniently removes the gothic and predominantly meditates on a fevered erotic psychodrama at Heights Grange. Following her previous directorial outing, Saltburn, Fennell once again leans into decadence, spectacle, and provocation.

Admitting her reverence for the novel in her recent interviews, stating she could never encompass its greatness, only attempt to recreate the feeling it gave her; that feeling, here, translates into something feral, lust-driven, and deliberately and unconventional adaptation that reeks of the director's own projection of the film.

And why not? One may argue that the film is as much for the lovers of the 19th century literary classic as for the movie lovers. While being true to its boiled-down version of the 1847 novel, the director of "Wuthering Heights" makes it her own by presenting the story through a new filter all while remaining respectful to its original source material.

"I'm kind of fanatical about it, so I knew right from the get-go I couldn't ever hope to make anything that could even encompass the greatness of this book. All I could do was make a movie that made me feel the way the book made me feel," she said in an interview. And so, we're presented the horniest adaptation, with absence of the wilderness of the moors and the brooding Machiavellianism of Heathcliff.

What we are presented with is a story of yearning and revenge that touches base with BDSM rather than the complexities that gender, class, and status have on one's psyche and relationships. It's utterly absorbing as the heightened energy, audacious sexuality, and striking visuals make it wildly fun, almost like a fever dream brought vividly to life.

Yet the question naturally arises: can this bold reinvention still be called faithful to Brontë’s novel?

And this is where all the rage comes in.

You may also like

Visually, the film is undeniably striking. The set design is sumptuous, the colours loud and saturated, the symbolism on point and the casting, especially young Heathcliff (Adolescence star Owen Cooper) but it is far removed from the grime and gloom readers associate with the Earnshaw estate. Rather than the moors becoming a present character in the plot, it is sidelined as something that exists within the Grange as a piece of landscape and the decadence of Wuthering Heights feels too stylised.

What works well though is how power dynamics are most sharply felt through Nelly’s positioning as observer and reluctant participant and her turmoil having lost a dear friend in Catherine, yet Elordi’s Heathcliff, though undeniably magnetic, lacks the ruthless calculation and long-game vengeance that make Brontë’s creation so disturbing.

Elordi lacks the darkness and Machiavellianism of the character created in 1847, rather his vengeance feels charmingly justified. The reasons for his brute nature are restrained by the consequences of his relationship to Cathy far more than to his circumstances and the struggles he endures to be incorporated socially. And in doing so, as handsomely as Elordi plays the tortured antihero, when he is rejected by Catherine for the status and position in society that Mr. Edgar Linton has to offer in marriage, it isn't as heartbreaking as one expects. And of course, one could be too distracted by his transformation as the archetypical brooding romantic lead in the second half of the film (frankly, the OG Heathcliff would've despised it).

Robbie’s Catherine—later Catherine Linton—similarly struggles to embody the novel’s central quandary. On the page, Catherine is volatile, self-destructive, torn between wild passion (Heathcliff) and social ambition (Mr. Linton). In Fennell’s telling, that tension is often eclipsed by heavy-handed sexual charge and eroticism. Her fits of temper feel aestheticised rather than psychologically destabilising.

Edgar Linton, too, is flattened. In the novel, he is well-bred, tender, and constant—almost the ideal gentleman—yet ultimately ineffectual against Heathcliff’s brutality. Here, he risks becoming little more than a foil to mock: a privileged obstacle rather than a tragic casualty of forces beyond his comprehension.

However, the movie is made for a sexually liberated contemporary audience, embracing a bold reinterpretation of a classic novel. It is one that emphasises the frustration and pursuit of sexual and financial desire.

Perhaps a relief for ardent fans of the literary classic would be to see it as Fennell’s retelling and not a strict adaptation. In this way, the adaptation succeeds in capturing the obsessive passion and emotional intensity at the heart of the story, even if it majorly sacrifices the social realism, haunted love and generational depth that grounded Brontë’s original.