As mainstream Indian films continue to find themselves on shaky ground both commercially and critically, we have steadily retreated into the past to find some consolation. Regular theatre reruns have been back for at least a couple of years, but the restoration of films that put the 'cinema' in Indian cinema could probably be a way to reflect on what first brought people to the movies. This year itself, after Ray's Bangla tour de force Aranyer Din Ratri (1970), Bimal Roy's more thematically accessible Do Bigha Zamin (1954) is now headed to one of the world's most prestigious film festivals—Venice 2025.

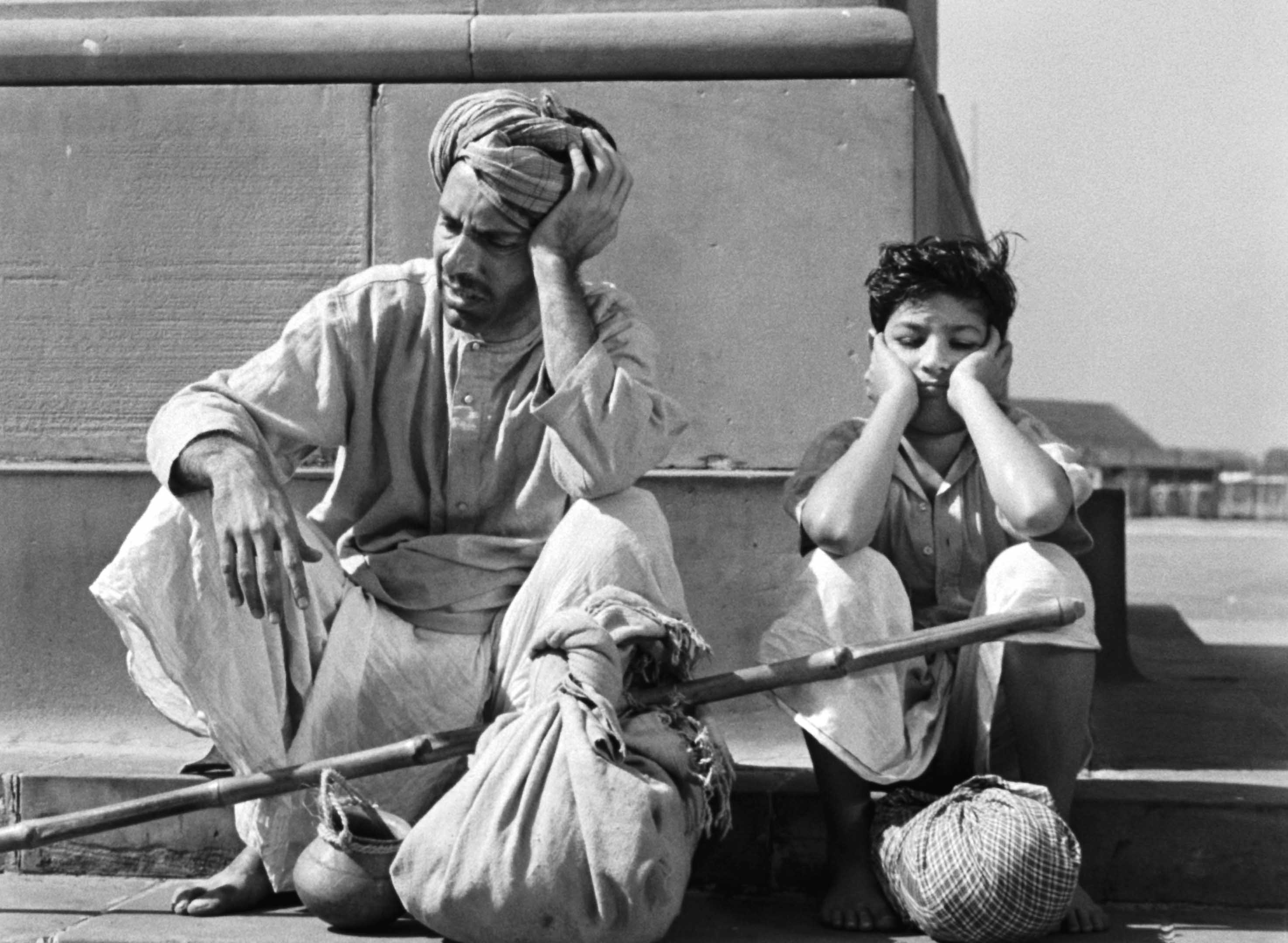

An early and powerful example of neo-realism, subtly weaving its socialist message into the fabric of a compelling narrative, Do Bigha Zamin was famously inspired by Italian maverick Vittorio De Sica's Bicycle Thieves (1948), a film generations across the world have resonated with. Roy fashioned a poignant narrative centered on a destitute farmer’s relentless struggle against dispossession by a ruthless landlord. With only three months to repay his debts, the farmer ventures to the city with his young son, resorting to strenuous labor as a rickshaw-puller while his child becomes a shoeshine boy. Amidst the harsh realities of urban life, the father and son forge new bonds within the slums, yet are met with relentless adversity as they strive to reclaim their land. Despite their resilience and tireless efforts, they ultimately fall short, losing the cherished land that once sustained them to encroaching industrialisation.

You may also like

Earlier this year, a restored version of Ray's perennially under-celebrated masterpiece Aranyer Din Ratri was screened at Cannes. Hollywood darling Wes Anderson, known to have publicly spoken of his admiration for Ray, helmed the film's six-year restoration, as he and the film's leading ladies, Sharmila Tagore and Simi Garewal, made their way to the French Riviera for the screening.

In Venice, members of the Roy clan—daughters Rinki Roy Bhattacharya and Aparajita Roy Sinha, and son Joy Bimal Roy—alongside Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, director of the Film Heritage Foundation, will lead the screening.

The painstaking restoration of Do Bigha Zamin began in 2022, the result of a collaborative effort between The Criterion Collection, Janus Films and the Film Heritage Foundation. Over the course of more than three years, this cinematic resurrection unfolded with care and precision. The Film Heritage Foundation began by locating the original camera and sound negatives—precious materials entrusted by the Bimal Roy family to the NFDC–National Film Archive of India for safekeeping.

But what they found was far from pristine. The reels bore the scars of time: torn frames, invasive mold, persistent water damage, and other serious signs of decay. Expert conservators began the delicate work of repairing these fragile materials, preparing them for a second life. Once stabilised, the reels were transported to the renowned L’Immagine Ritrovata lab in Bologna for advanced restoration.

Yet the challenges didn’t end there. Key elements were missing: the original opening titles and the final reel of the camera negative had vanished, and the sound negative suffered from dialogue dropouts and audible interruptions. The missing pieces were eventually filled with the help of a rare dupe negative—printed on Dupont/Kodak stock in 1954–55 and preserved at the British Film Institute—allowing the team to piece together a more complete version of this neorealist classic.

You may also like

Screenwriter-poet Gulzar, who "learnt filmmaking from Roy" says, “This film is historic as it changed the way films were made in India. After Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar, which won an award at the Cannes Film Festival, this was the second Indian film to win at the Cannes and receive international recognition. The most important element is that all his films right from the Bengali ones which he made and the Hindi films which he made, all these films were based on literature. Not many people know that Do Bigha Zamin is from a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, which was also called Do Bigha Zamin. I started working with Bimal-da, who we used to call Dada, from the film Kabuliwala when I was his chief assistant. I have very fond memories of that time. In those days, the picture and sound negatives were separate and when they were brought together optically to make the release print, it would be called a married print. Bimal-da would shoot two shifts in a day – 7 am to 2 pm and 2 pm to 10 pm and would then sit in the editing room working till late night at Mohan Studios. People would say that he is married to films. Bimal Roy was the coolest director I have ever seen.”

The relevance of Do Bigha Zamin in today’s India is both chilling and urgent. At its core, the film is about dispossession—how systemic forces conspire to strip a man of his land, his dignity, and ultimately his belonging. It’s a story of migration, debt, exploitation, and survival. And despite being made in 1953, that story has not aged. In fact, it has only deepened in resonance.

India today remains sharply divided along economic lines. Millions still live with precarious access to food, housing, healthcare, and employment. Large swathes of the population—informal workers, landless laborers, urban migrants—remain vulnerable to the same exploitative pressures the protagonist of Do Bigha Zamin faces. The film’s depiction of a man uprooted from his rural home and forced into anonymous, underpaid labour in the city is a haunting parallel to the internal migrations we saw, for instance, during the COVID-19 lockdown, when thousands walked back to their villages with no state support.

"Do Bigha Zamin is an unspoken autobiography of Bimal Roy who was cast off from his home in East Bengal in a similar episode as the hero, peasant, Sambhu Mahato," reads a collective statement from the Roy family, adding, "He never recovered from this cruel separation from his beloved birthplace. In the brief lifetime accorded to our father, he transformed the profile of Indian cinema and was able to stir collective consciousness with his cinematic parables. Our father was a silent cinema poet and a visionary of profound humanism whose work shall continue to act as a beacon whenever dark forces threaten.”

And yes, the lavishness of the elite—manifested most grotesquely in extravagant weddings, billion-rupee private parties, and gated utopias—serves as a stark counterpoint. It’s not just an aesthetic or moral contrast; it’s a structural one. The upward spiral of wealth among the few is often built on the continued disposability of the many. The film’s relevance lies not just in its portrayal of poverty, but in how it lays bare the invisible architecture that sustains inequality.

You may also like

“When I was working as an assistant to Gulzarsaheb, he would often speak about his guru Bimal Roy. This spurred me to watch all his films right from the time he was a cameraman on PC Barua’s Devdas (1935) to his first Bengali film as a director, Udayer Pathey, to Do Bigha Zamin," says Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, Director, Film Heritage Foundation.

"In his films I was struck by the poetic visuals, the silences, the deep humanism and compassion that he showed in the social themes of his films that highlighted the plight of the marginalised, the issues of migrant labour, and the urban-rural divide that are still so relevant today. For me, Do Bigha Zamin changed the face of Indian cinema that brought filmmakers out of the studio to begin shooting on the streets.”

Dungarpur adds that his foundation has partnered with Criterion and Janus to restore three other Roy classics—Madhumati (1958) and Bandini (1963), alongside Devdas (1955).