It’s the kind of film that deserves every bit of the hype it’s getting, and how often does one get to say that about a movie these days?

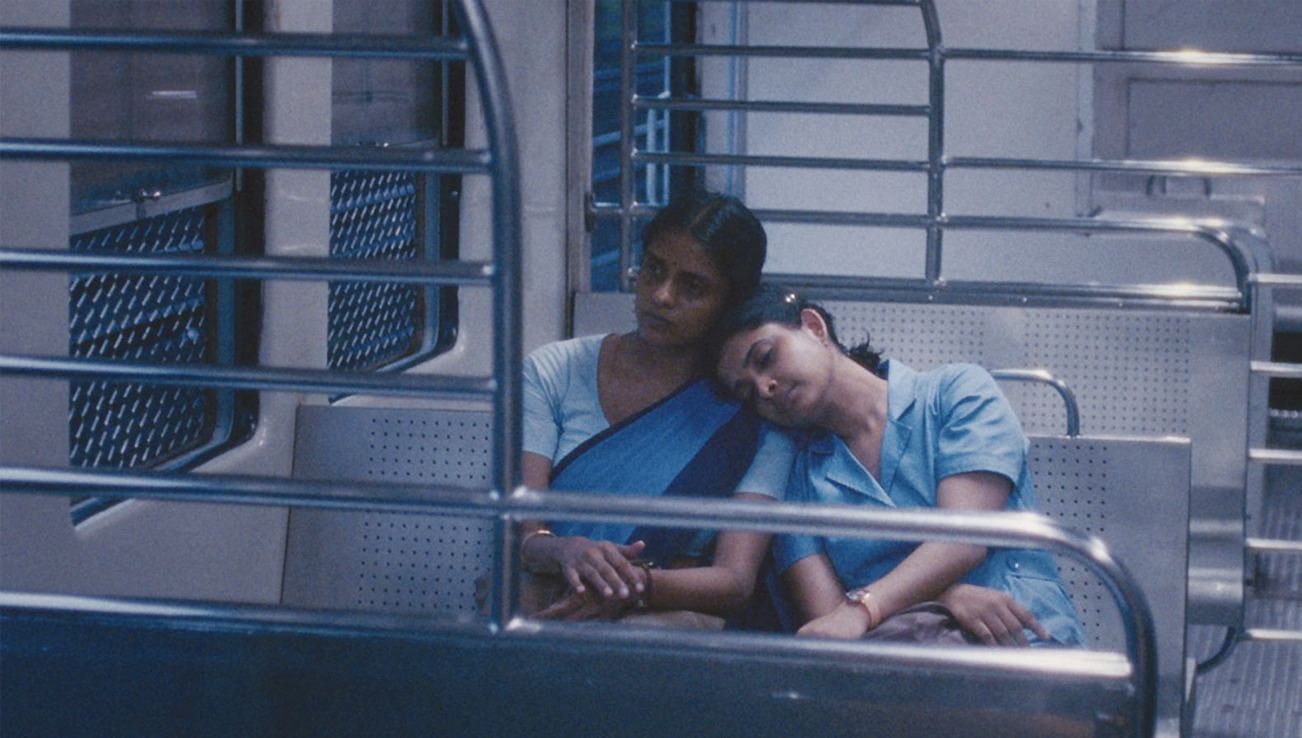

All We Imagine as Light is a hauntingly poetic reflection of urban loneliness, love, and identity. Payal Kapadia’s nuanced take on three women navigating life and love in Mumbai is the stuff masterly movies are cut from. Even the city, blue with its characteristic tadpatris, is a cocharacter of theirs, embodying fantasies, and despair to be shared between them.

But Kapadia also does the (almost) impossible: she introduces males, equally complex and no less necessary, in this female-centric movie.

This is not a movie about hollow male bashing or pseudo-feminist caricatures. Men in attendance, absent, and even anonymous make up those subtle intricate fibres inside the larger tapestry that makes up women's lives. The filmmaker doesn't leave them in the darkness of her radiant female protagonists but instead, gives depth, contradictions, and even humanity to these individuals.

Kapadia's men aren't perfect, but they're not meant to be. They inhabit the margins and the interstices. They reside in the shadows cast by the film's radiant feminine figures. And it's in these shadows that they are reborn.

The All We Imagine As Light men aren't about heroism or villainy; they're something much more interesting: shadows, spectres and catalysts.

Shiaz: A Lover’s Fractured Reflection

Shiaz, the young Muslim man who is utterly enamoured with Anu, is a character Indian cinema rarely sees. Soft, vulnerable, and disarmingly honest—qualities often denied to male characters, especially in stories about cross-cultural romance. His love for Anu is sincere and tender but carries the quiet burden of societal judgment. Shiaz isn't a man you root for, but he's also not one you can dismiss. In terms of Anu, their relationship is full of contradictions. He loves her hard; in fact, he loves her obsessively, but wrapped in insecurity, and the insecurity corrodes everything that it touches.

There's a scene in the movie in which Shiaz tells Anu that the thought of being with her scares him. It's not based on fear of her love or anything for that matter; it's the crushing reality of living in a country like modern India and making a Hindu-Muslim relationship work. Yet, with her, he becomes whole. Kapadia paints a pretty picture about how love can both be a haven and a battleground.

Then there is that scene in the sunglasses shop which reads jarring at first, but reveals so much more about Shiaz's character in his curiosity to know the sort of men Anu comes across at work as a nurse and does make her male patients aroused. It is charged with tension almost to a boiling point. His jealousy is almost weird, but Kapadia frames it not as an act of dominance, but as a symptom of his own unravelling.

Manoj: The Stillness of Unspoken Love

While Shiaz is chaos, Manoj is stillness. In one way, the film is trying to present Manoj as an opposite to the classical image of the male wooer. He makes no great declarations or pompous gestures of love. He just forwards books of poetry to her, bakes sweets for her, and turns up when she needs him. He is a presence, not a force. Manoj tells Prabha that he is leaving Mumbai because the city's been unkind to him, that his words carry the weight of sadness and disappointment; "Is there a reason I should stay? " he asks her, his voice drawn to vulnerability. The question isn't about her but a question on his future, an anchor needed in a city that is too vast, too indifferent.

Manoj’s story is a testament to the power of subtlety in storytelling. He’s not a man of action, but a man of feeling, and his unspoken pain lingers long after the credits roll. The film takes a character who could have been a throwaway “nice guy” and turns him into a symbol of quiet heartbreak.

Prabha’s Husband: The Ghost of Absence

If Manoj is a portrait of quiet devotion, Prabha’s husband is the embodiment of emotional neglect. He doesn’t even have the luxury of having a name in the movie. A man who exists only through his absence, he becomes a haunting presence in Prabha’s life. They haven’t spoken in over a year, and yet she clings to the idea of their marriage, tethered to him by nothing more than hope. He’s an absence, a ghost, a void that looms over her life. And yet, his presence is felt in every frame of her story. The German rice cooker he sends her—a faceless, nameless gift—is both a lifeline and a cruel reminder of his apathy.

In one of the film’s most gut-wrenching scenes, Prabha hugs the rice cooker in the dead of night, as if willing it to fill the void her husband has left behind. It’s a moment that lays bare the toxic nature of hope—the way it can bind us to people who have long since abandoned us.

He’s not a villain. He’s not even cruel. He’s just gone. And sometimes, that kind of absence can be more devastating than any act of betrayal. Prabha’s husband represents a masculinity that’s all too familiar: distant, avoidant, and emotionally unavailable. He doesn’t tell her to move on, doesn’t offer closure, doesn’t even acknowledge her existence. And yet, his absence looms large, shaping her choices, her identity, her life.

The Anonymous Rescued Man: A Vessel for Closure

Perhaps the most puzzling character in the entire film is the man Prabha rescues from the sea. He has no name, no previous life, and no form of identity. He is a blank book, a cipher, which is exactly what makes him so exciting. In caring for this man, Prabha begins to care for herself too. She unleashes the weight she has been carrying about to face up to the vacuum her husband left behind.

What is interesting about this character is that he straddles the line between reality and imagination. He isn't a character; he is a vessel. Kapadia deliberately writes this character nameless. He's not meant to be understood. He is at the same time human and metaphor, reminding us, at times, that it's the people we save end up saving us.