Why There’s No Match To A Great Catch In Cricket

They say a catch can win a watch. But it also turns cricketing athleticism into pure cinema for the ages. We dive—deep — into why such moments captivate long after they've passed

It was the perfect Indian summer. A backyard gully cricket match. Just the right amount of heat in the air.

The sun was on its downward trajectory, but there was enough light to glimpse the withering shine on the white plastic ball that cost a couple of rupees. With a faux seam and the World Cup trophy design embossed on its surface, it was our little globe of fun in a world of expensive tennis balls.

Law 33 of the official set of rules, the Laws of Cricket, says: “The striker is out Caught if a ball delivered by the bowler, not being a No ball, touches his/her bat without having previously been in contact with any fielder, and is subsequently held by a fielder as a fair catch... before it touches the ground.”

In street cricket, we 10- and 11-year olds were the lords of our own rules. A one-handed catch after a single bounce was enough to send the batsman packing.

It was a five-a-side game. One of my friends took stance in front of the makeshift stumps—a rickety old plastic chair. He struck the very first ball back from where it came—towards the bowler. A cracking straight drive, the ball was moving too fast for the bowler to fiddle with it. I saw it heading towards me, the last fielder at the end of the gully. Fail to stop it, and it’s a boundary.

The plastic ball moved wildly on the gravel, like it had a mind of its own. Catching it was like grabbing the golden snitch. As soon as it bounced, I readied myself but misjudged the ball’s trajectory as it swerved after bouncing once. This was not waist height. This was going to fly over my head.

From a natural crouching fielding position, I readjusted myself. I leapt off the gravel, throwing my right arm upwards, clutching the plastic ball in my right palm. The rough surface of the speeding ball swirled against my skin as the ball deposited itself in my grasp. My friends rushed towards me in jubilation. This was a catch for the ages—at least in the gully.

I wonder if that's how Glenn Phillips felt after his catch ended Virat Kohli’s stay in match 12 of the 2025 ICC Champions Trophy? Playing his 300th ODI, Kohli slashed confidently at a Matt Henry delivery bowled short outside the off stump. The ball flew off the bat’s blade—a resounding thwack—but met an unmovable force in the form of Phillips at backward point.

It happened so fast, the broadcast camera panned past Phillips before realising the ball wasn’t racing to the boundary but sat snug in his giant right hand.

Kohli stood in disbelief, eyes wide behind the grill. It was as if he’d seen a ghost. Did that really happen? “You can put as many words as you want. But the expressions tell you the story,” said commentator Harsha Bhogle. “The batter. People in the stands: ‘what did we just see here?’ That was not meant to be caught.”

We love sport for its unpredictability—for those moments when the impossible is made to look effortless. And few feats capture that better than a truly great catch. They’re the highlights that echo through history, the split-second plays that tilt the match and drop jaws.

We all recognise a great catch when we see one. Whether it’s a miraculous grab on the world stage or a flying one-hander in a backyard gully. What we don’t always know is what it takes to make it happen. Is it instinct? Or is it an elegant collision of timing, precision and mental clarity—a kind of choreography between body and mind?

You may also like: MS Dhoni is IPL's biggest question mark right now

As someone who grew up loving the game—and fancied himself quite the catcher—I set out to understand what really goes into that mid-air moment. To explore the pursuit of mastery behind the art of the catch.

As for Phillips, this wasn’t the first time the New Zealander had pulled off a remarkable moment in the field. The 28-year-old has an incredible leap. Often, when he lands back on the ground, it’s with the ball in his hands.

He took a similar catch—this one was to his left—to send Pakistan’s Mohammad Rizwan back to the pavilion during the opening match of the tournament. Standing at backward point, close to where he was stationed for Kohli’s catch, Philips leapt towards the ball as Rizwan sliced a Will O’Rourke delivery.

Slow-motion highlights will show you how Philips’s instincts first tell him to bring both his hands together as he spots the ball coming in his direction.

That, however, changes in a split second. He knows he can’t reach the ball with both his hands as it arrives at a rate of knots. He sticks out his left hand—almost an unreal extension of his airborne self. Before he knows it, the ball is past him, but not past his left hand. Commentator Ian Smith immediately dubs it an “unbelievable grab”.

“It’s becoming a little bit of a thing, isn’t it?” Philips commented on the catch in a post-match interview. “With the way Will (O’Rourke) bowls, there is the odd chance for it to be a cut shot. I think you know you’re in the game for certain elements of time. I definitely felt like I was in the game there. I just stuck it out and it stuck.”

On the TV screen, such catches seem easy. But when the player is in full flight, there’s no other way than to trust your grip and the ground. It is an intricate three-way relationship.

You may also like: Is Delhi Capitals IPL's Worst Side?

Like Phillips, Jordan Silk is not afraid to fly and often test this equation. The 33-yearold Australian has made it a habit of pulling off wonder catches in Australia’s Big Bash. The numbers back the Sydney Sixers recruit’s electric fielding abilities. In 135 Big Bash matches, he has pocketed 85 catches. Hailed by Ricky Ponting as one of the best fielders in Australia, the two-time Big Bash champion went viral in 2015 when he took an incredible running, diving catch. Even Sir Vivian Richards described it as “one of the best catches” he had ever seen. Sydney Thunder’s Chris Greene top edged a delivery from Sean Abbott up high.

Silk and Steve O’Keefe, both in pursuit of the shooting star falling back to Earth, were about to converge—the latter running in from the in-field. It had the makings of a painful collision, but Silk had no time for caution as he sprinted from deep mid-wicket, keeping his eyes on the ball, his body tilting forward every moving second. As he reached closer to the ball, he leapt forward like a flying pink gazelle. The ball was dying on him. But just before it could touch the ground, he stuck out his right paw to catch the ball. Silk slid across the grass as momentum took him past the onrushing O’Keefe.

"Catching the cricket ball is one of the hardest skills because your hands are going away from the body in the most difficult catches. And when your body is in motion, it makes this job more difficult,” says former cricketer and IPL veteran Rajat Bhatia, assistant coach at the Lucknow Super Giants and a human biomechanics specialist. “The body loses its centre of mass and when that happens—you, in turn, lose balance, especially when taking a catch.”

As an assistant coach, Bhatia is not only key to team strategy but also brings expertise in athletic performance and technique. No wonder the Lucknow Super Giants’ Instagram feed has plenty of videos showing fielding and catching drills that are now part and parcel of the game. Be it batter Matthew Breetzke practising a running catch or Aiden Markram perfecting the boundary juggling catch. First exhibited by Australia’s Adam Voges in a T20I versus New Zealand in 2009, the grab demands technique, presence of mind and loads of skill.

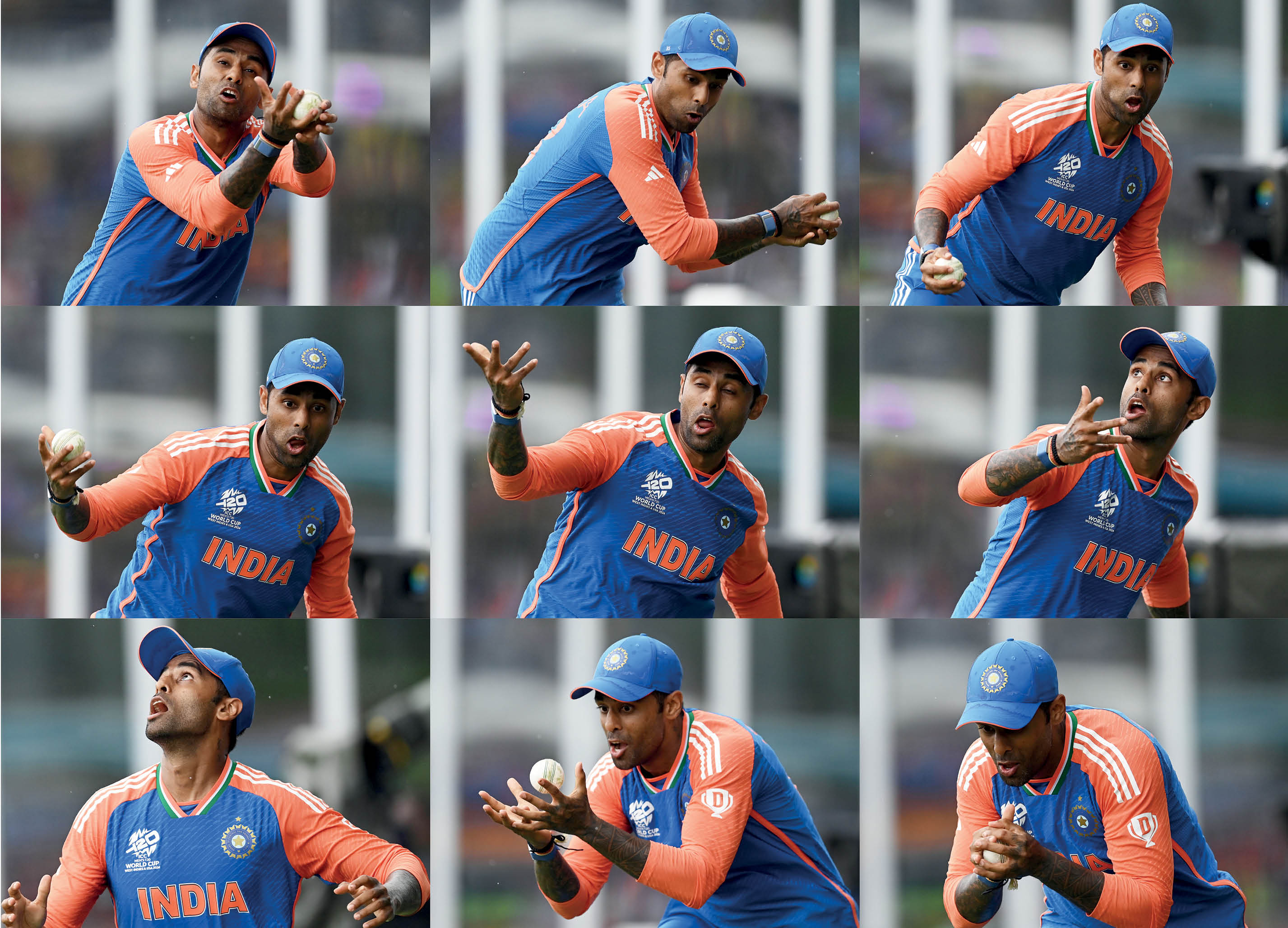

For instance, one must master the art of letting go—quite literally—and then seizing the moment (and the ball) again. Suryakumar Yadav must have felt this during the T20 World Cup final last year. With one over remaining, South Africa were 16 runs away from their maiden ICC trophy. David Miller was in control, a couple of strikes away from crushing the Indian dream of winning a World Cup after 13 years.

Miller struck a wide full toss from Hardik Pandya down the ground. It had the legs and the elevation to go all the way. “Wide! Miller hits it. And he gets plenty of it! Does he? No!” Ian Smith called from the commentary box as he jumped off his seat.

Running in from wide long-off, almost parallel to the boundary line, Yadav caught the ball with his two hands while barely remaining inside the boundary. But with his momentum taking him past the line, he tossed the ball in the air before crossing the boundary, took three steps, tiptoed back into the field of play with the poise of a seasoned ballerina and grabbed the ball once again, registering a legitimate catch. The rest is history.

In recent years, the boundary line has become a focal point for these kinds of catches. In post-match interviews, India’s former fielding coach T Dilip and Yadav both admitted that the latter must have practised a catch like that repeatedly. “He must have taken 50 catches like that in practice,” Dilip explained in a post-match interview. “But in a match, when that moment comes, it’s his decision and being aware about where the rope was.”

Australian Jake Fraser-McGurk who took a similar blinder close to the boundary line for Delhi Capitals against Sunrisers Hyderabad during the ongoing IPL, seconds that. “You try and follow the ball. Then, if you have to do it, you have to do it… It’s years and years of practice. Obviously, you have got to be athletic, get into the gym to have that power to jump. It’s repetitive stuff,” Fraser-Mc-Gurk explained in a post-match interview.

Sports presenter and commentator Suhail Chandhok says Yadav’s catch epitomised the evolution of fielding itself and the hours that go into practising for a moment just like that under pressure.

He explains how modern-day fielding is no longer just about reflexes or agility but the combination of anticipation, spatial awareness and athleticism, all while maintaining a still head under pressure.

“Surya’s ability to sprint full tilt, judge the trajectory to perfection, while being aware of exactly where the rope was, showed us that catching today demands as much creative instinct as technical skill. He made an extraordinary effort under pressure seem effortless,” he adds during an interview.

Indian cricketer KS Ranjitsinhji wrote in the Jubilee Book of Cricket, 1897: “...It is best to... take [a catch] standing still with both hands. But sometimes, of course, this is impossible, and a really brilliant catch may be made by a fine fielder running hard and using only one hand.”

Indeed, it doesn’t matter where you’re standing on the field—near the batsman, at silly point or short leg, or far away on the boundary line, away from the action. A great catch can come from anywhere. Sometimes, a bowler might be rushing towards a firmly hit ball and still brace themselves for a catch. Former West Indies all-rounder Dwayne Bravo, who is currently a mentor for Kolkata Knight Riders, found himself in that situation 20 years ago during the side’s 2005 Adelaide Test against Australia.

You may also like: Neeraj Chopra aims for a new high

Still in his follow-through, Bravo flew to his left as the ball came back towards him off a leading edge of Shane Warne. The Trinidadian lobbed his five-feet-nine-inch frame towards his left to reach the ball with his weaker hand. When he grabbed it, the last part of his body in touch with the ground was the toe end of his left shoe, which left a speck of dust from the grassy pitch hanging in the air. He crash-landed back on the grass, the ball in his grip, and wheeled off for an epic celebration.

“Now, a brilliant catch or a run out or a save can make a big difference in the game,” says the 41-year-old in an interview with Esquire India, smiling wide as he watches the catch again on video. He goes on to watch a highlight reel of another catch he plucked out of thin air at short midwicket to send Adam Gilchrist packing at the Melbourne Cricket Ground the same year. “I enjoyed just doing something spectacular. And I was a goalkeeper as a kid, so anytime the ball was close to me, I just enjoyed diving,” says Bravo, who is also among a select group of individuals who have 1,000 runs, 50 wickets and 50 catches in ODIs. He has 73 one-day catches and 41 Test catches to his name.

Long on, long off, mid-wicket—Bravo says these are some of the hotspots on the cricket ground where exceptional fielders thrive. “So, you see a lot of players are spending more time in the field and I think it's good for the game, it’s good for the sport. They no longer have fast bowlers or spinners who can’t field anymore,” he adds.

As mentor at Kolkata Knight Riders, Bravo says he wants the players to enjoy fielding and put themselves in positions where they want the ball to come to them. "You want players to go to those hotspots. Like (Andre) Russell and Rinku (Singh)... But it's good that we have a group that has quality fielders," Bravo adds.

But what is it about watching a great catch on repeat? It’s the equivalent of a 40-yard free kick in football that bends into the top corner, a fingertip save that wins a team the World Cup, a nine-dart finish in the sport of darts, or a winning three-pointer in a tense basketball game as the buzzer ticks to zero.

“In sport and as athletes, we live to seize the big moments and etch ourselves into history books. For fans, those moments become memories… Sport is a tapestry of tiny moments woven together to make for special viewing,” says Chandhok.

So, where does the art of catching the cricket ball go from here? T20 cricket has afforded plenty of innovations to the sport, primarily with the bat. But the catchers aren’t too far behind. Expect more relay catches, one-handed wonders and fielders putting their bodies on the line in a format where a single run can make or break a cricket match. As one of India’s most lethal fielders, Mohammad Kaif, once said about the secret to terrific fielding and catches: “You must be prepared to get hurt.”

“The art of fielding will change when the game gets shorter. When the game gets faster, your fielding has to be quicker,” Bhatia explains. “It’s like how you run in a marathon as compared to how you run a 100-metre dash.”

As a viewer, you must keep your eyes peeled for the next spectacular rabbit out of the hat. When it comes to taking a great catch—especially when no one in the stadium or the gully expects you to—all it takes is a moment. Blink and you will miss it.

To read more stories from Esquire India's April 2025 issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest newspaper stand or bookstore. Or click here to subscribe to the magazine.