What's Next For The IPL?

The world’s richest sports league, second only to the NFL, the Indian Premier League has enthralled audiences with exhilarating cricket on the field and controversy off it. The challenge now? Keeping that spark alive

When the Indian Premier League was launched in 2008, it seemed to go against every image India had created about itself. And yet, contrarily, it symbolised the essence of a new emerging India—a little brash, a little out there, a little minus finesse you might say, but unabashedly festive and celebratory.

Pop sociology apart, the IPL provided a platform that purists may decry. A gateway for talent that would never have made it through the stringent alleys and small openings to the Indian cricket team. A platform for livelihood and self-actualisation, most pertinently manifest in earnings which were beyond the grasp of most. And a chance for spectators who did not really understand the gravitas-laden philosophy of Test cricket to partake of the subcontinent’s favourite sport.

Apart from the sport and the spectacle, the IPL has entertained us not just with spectacular performances—individual and collective—but also everything else that is symptomatic of Indian life: intrigue, politics, corruption, excellence et al. This April, the league will mark its 18th season. In late 2024, Brand Finance, an international agency that assesses global sports properties, ranked the IPL

as the second most valuable at $12 billion. Only behind the National Football League (NFL), which is almost nine decades old now.

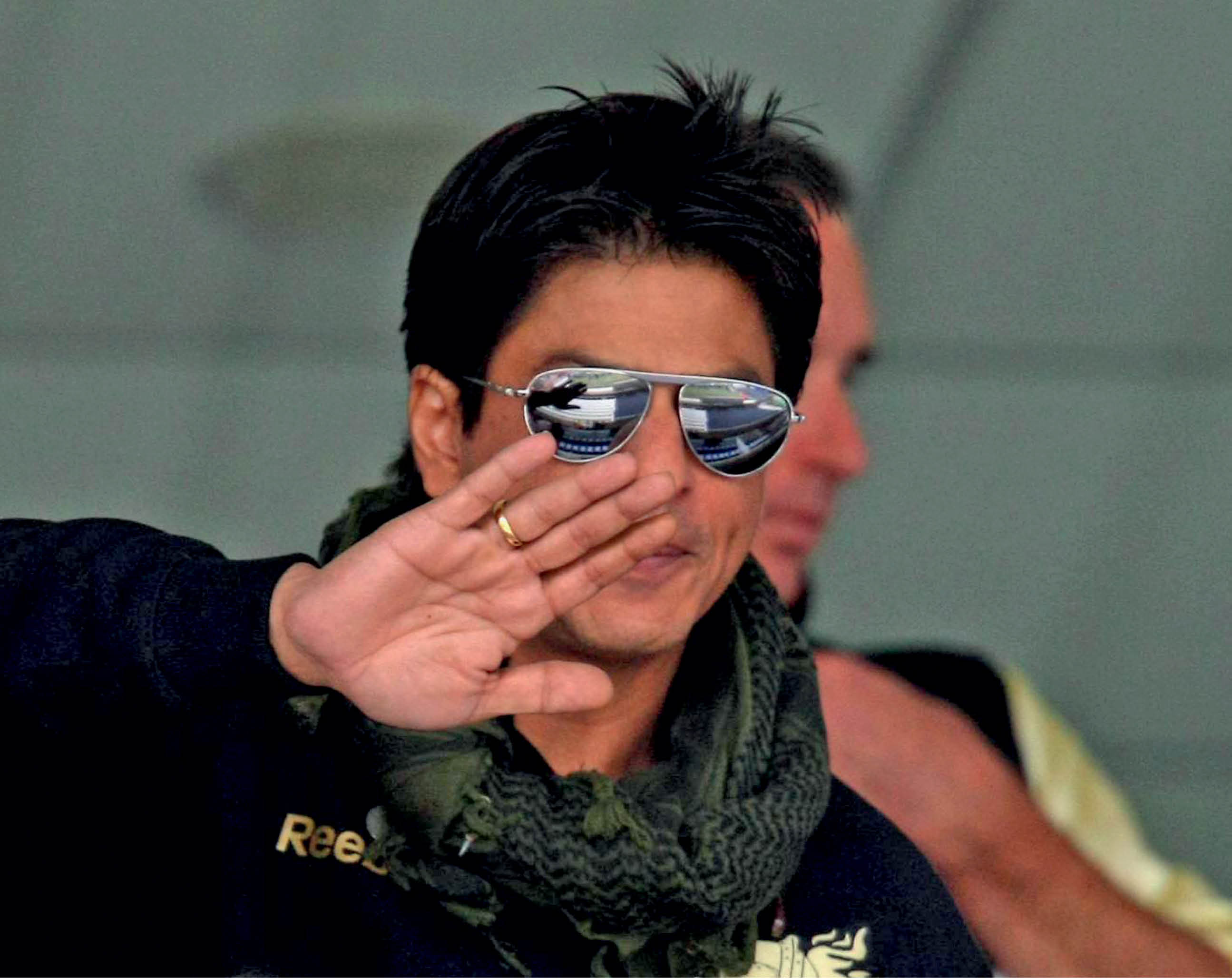

You May Also Like: SRK at the IPL Inauguration

In a short span, the IPL has leapfrogged over legacy sports leagues such as Bundesliga, Premier League, National Basketball Association, Major League Baseball. In 2009, a year after it started, the tournament was valued at $2 billion. The exponential growth since marks it out as a phenomenon. The Indian Premier League has not only galvanised cricket from a doddering existence into a dynamic sport that is now expanding to new geographical and financial frontiers.

The IPL's success is not from a linearly consistent sequence of events. The 12-month period that preceded its birth was a period of tumult, the likes of which has never before, or since, been seen in Indian cricket.

In April 2007, hot favourites India were bumped out of the ODI World Cup and coach Greg Chappell, who had been at loggerheads with some of the leading players, was virtually forced to quit. Despite the setback, India did well to win a Test series in England, for the first time since 1986. But there was more strife, as skipper Rahul Dravid decided to step down from captaincy.

In the background, an internecine power struggle in the BCCI started between old buddies Jagmohan Dalmiya and IS Bindra. Their bitter fallout was reaching flash point.

Among those aligned to the Bindra faction was Lalit Modi, scion of a prominent business family. He had had a couple of business misadventures behind him, but his skyscraper ambition to make it big remained intact. Straddling the Bindra-Dalmiya factions was political cal majordomo Sharad Pawar, who had used his considerable clout and influence to become president of the BCCI. Keeping BCCI politics on the boil during this period was the upcoming telecast rights for Indian cricket which had boomed since the arrival of cable TV in 1996. Among those vying for the rights this time was Zee TV, the country’s biggest media house.

You May Also Like: India's Greatest Cricketing Moments

On the cricket front, meanwhile, the challenge was to pick a squad and captain for the inaugural T20 World Cup coming up in September. Dravid’s resignation as captain had caught the selectors off guard. To queer the pitch further, Sachin Tendulkar, VVS Laxman, Sourav Ganguly and Zaheer Khan, were unavailable for the tournament for reasons of fatigue or disinterest in the new format. The BCCI itself wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about the World Cup either. India, in fact, was the last to join the tournament. A squad made up largely of younger players and some second stringers was selected, and MS Dhoni was named captain. India went to South Africa as no-hopers.

The T20 World Cup turned out to be a black swan event. India beat arch-rivals Pakistan twice in 12 days —first in a Super Over thriller, then in a nerve-tingling final. In between, Yuvraj Singh slammed Stuart Broad for six sixes in an over. Mesmerised by the thrills and spills of the new format accompanied by its populist trappings like cheerleaders and blaring music, etc., India, starved for success in a multi-nation tournament, went ballistic.

Witnessing the tournament first-hand was Lalit Modi. Weaned on sport in America while studying there, he had envisioned a private-owned multi-team tournament years earlier, but the BCCI, run by an Old Boys Club, scoffed at all suggestions. His opportunity came unexpectedly when Zee TV’s bid for Indian cricket’s telecast rights was rejected by the BCCI. In retaliation, Zee’s Subhash Chandra launched the Indian Cricket League (ICL). The BCCI swiftly chose Modi to counter, and the IPL was born weeks later.

Modi acted quickly, imposing a life ban on Indian players joining the ICL, blocking the ICL from using official grounds, and negotiating with other cricket boards to prevent their players from joining.

Despite these measures, the challenge of appealing to the public remained. However, Modi had an astute understanding of the business of sport and found a way to combine the country’s enduring passions of cricket, cinema and big money into his vision.

This alchemy proved irresistible to the Indian cricket market, fans and sponsors. The sale of franchises player auctions were broadcast, whipping up worldwide hysteria. There was no dearth of sceptics. However, the first game of the first season proved their misgivings misplaced.

The match between Kolkata Knight Riders, owned by Bollywood luminaries Shah Rukh Khan and Juhi Chawla, and Royal Challengers Bangalore, owned by flamboyant businessman Vijay Mallya, was played at Chinnaswamy Stadium, highlighted by Brendon McCullum’s spectacular hitting. He lit up the night with a fusillade of fours and sixes that had the capacity crowd in thrall. McCullum hammered 158 off just 73 deliveries, outscoring the opposition, RCB, by almost twice as many runs, as KKR romped home by 140 runs.

You May Also Like: Kavya Maran's Geometric Sunglasses at IPL Match

The aura of the occasion, razzmatazz accompanying cricket and McCullum’s unbridled hitting cast a spell on the crowd, sending them into absolute delirium. Television viewership for the match broke all records. In film industry parlance, the IPL was a superhit just after the first show.

It hasn't been all smooth sailing in the past years. From the inaugural season itself, the ride was bumpy. There were several hiccups, hurdles, controversies, corruption allegations, maladministration, devious perfidy and financial skulduggery in the first few years—some even giving rise to clarion calls for the league to be shut down, before the IPL settled into a rhythm that wasn’t constantly fractious, suspicious and inviting harsh scrutiny.

The first season was a rousing success, throwing up several outstanding performances, topsy-turvy results and an unexpected champion team in Rajasthan Royals. The cheapest franchise with the least number of stars beat teams filled with marquee names. This confirmed the utter unpredictability of T20 cricket and made the league even more endearing.

One major headline moment of the league had little to do with cricket, when Harbhajan Singh slapped S Sreesanth during post-match handshakes, leading to Harbhajan’s ban and fine; however, this was a minor misdemeanour compared to the 2011 crisis involving IPL Chairman Lalit Modi and Congress politician Shashi Tharoor over the ownership of the Kochi Tuskers Kerala franchise. Tharoor’s wife, the late Sunanda Pushkar, had a stake in Kochi, which Modi claimed was irregular. Modi by now was running afoul of his own board over several issues, including the allocation of IPL telecast rights and the shareholding pattern of Rajasthan Royals, in which his brother-in-law had a stake. To cut him down to size, the BCCI ratified Kochi’s inclusion in the IPL.

The ensuing public feud between him and Tharoor captivated the nation, but the fallout led to Tharoor’s resignation, while Modi fled the country and hasn’t returned since. After just one season, Kochi was removed for failing to make its annual payment.

You May Also Like: India Vs Pakistan: 5 Iconic Victories For The Men In Blue

The more damaging controversy erupted in 2013 when betting and match-fixing hit the IPL. A Delhi police phone-tapping investigation revealed three Rajasthan Royals players colluding with bookies to fix match events. As the probe expanded, Chennai Super Kings, owned by BCCI president N Srinivasan, came under scrutiny. His son-in-law, Gurunath Meiyappan, exposed as a compulsive gambler in contact with bookies, intensified the scandal. The flame of corruption had reached the very backyard of the Indian cricket establishment itself!

Alarmed by these developments, the Supreme Court of India stepped in to stem the rot in Indian cricket. The Justice Lodha Committee, after protracted hearings which continued till 2016, came up with a slew of guidelines and rules to ‘cleanse the system’. Not all have been adhered to. But there has been no similarly damaging development in Indian cricket since.

Ironically, these controversies and setbacks did not diminish the appeal of the IPL. Viewership and fan following continued to grow by leaps and bounds, which had a direct impact on the brand value of the enterprise. When the league started in 2008, the broadcast rights were sold to Sony for approximately ₹4,300 crore for 10 years. In 2017, when the rights were bought by Disney Star for five years, the price had swelled to `₹13,600 crore. In 2022, the valuation had ballooned to a mind-boggling ₹48,390 crore for telecast (Disney Star), digital (Viacom plus other rights for five years (source: Economic Times online).

The remarkable growth story can be looked at from other aspects, too. For instance, in late 2021, when the league expanded to include two more teams, the Lucknow franchise was auctioned for `7,090 crore and the Gujarat Franchise for ₹5,625 crore (source: cricinfo, October 25, 2021). To give a comparison, in the inaugural year, the most expensive franchise, Mumbai Indians, was bought for $111.9 million or ₹487 crore approx. (source: cricinfo).

You May Also Like: Could Abhishek Really Be The Next Yuvraj?

On the face of it, the purchase prices for Lucknow and Gujarat may seem surreal, but in fact are located in the win-win formula of the IPL’s distribution of earnings.

After the initial 10-year lock-in period, in which the franchises had to pay the league an annual license fee, the revenue generated from media rights and some others is now ploughed back to the franchises. This works out to ₹240-400 crore a year, including ticket sales and sponsorships, which, barring gross mismanagement, should cover not only all expenses for the season, but also leave each team with substantial profit.

The impact of such growth is manifest in the player purchase purse available to each franchise for players during the mega-auction. It is now worth `120 crore. In 2008, this was approximately ₹20 crore and the most expensive player was MS Dhoni, bought by Chennai Super Kings for $1.5 million (then approximately ₹6 crore). (Source: timesofindia.com). In the 2024 auctions, the most expensive was Rishabh Pant, for whom Lucknow Super Giants paid ₹27 crore.

The success of the IPL spawned multiple such leagues across the world, but none has had quite the same impact. To a large extent, this has to do with the quality of cricket played in the IPL. It attracts the world’s best players because it pays the best money for exceptional talent. Across the world, many accomplished players playing currently in every format, have benefitted with the IPL as launchpad.

But in order to remain relevant, the IPL also needs to remain fresh.

Spectatorship in sport can be fickle, demanding new innovations and improvisations to keep interest in it alive. For instance, the IPL ‘After Parties’, notoriously newsworthy in the first couple of seasons, died a silent death soon. Cheerleaders are still around, but they have become far less central to the tournament’s ethos than when the league started. The signature tune, however, retains its appeal because it is intricately linked to the IPL’s identity.

Innovations like Strategic Time-Out have gained significance, adding an intriguing dimension to the passage of play. The verdict on the Impact Player rule, introduced in 2024, is unclear, but what was not in doubt is that fans and viewers are happy to test and taste innovations thrown up by technology-driven tools of the trade—for example, balls and bats having chips and mics embedded in them to capture data and drama of the action.

You May Also Like: New Cricket Books Every Fan Needs In Their Locker

The immediate issue confronting the IPL today is finding marquee names to peg the league on. And these necessarily have to be from India. In 2008, Tendulkar, Ganguly, Laxman, Dravid, Dhoni, Sehwag, Kumble were the iconic players on whom the enterprise was structured. Virat Kohli, Rohit Sharma, Ravindra Jadeja, Jasprit Bumrah succeeded these stalwarts to keep the brand value of the IPL soaring. From this cluster, the first three are in the winter of their career and have, in fact, retired from T20 international cricket. Young Turks Rishabh Pant, Yashasvi Jaiswal and Shubman Gill are gifted but whether they can take the baton to provide the IPL with scintillating performances and enduring star value over the next decade, remains to be seen.

The financial heft of the IPL is obviously its biggest strength. The Big Bash League in Australia trails at number two, but in money terms, the difference between the two leagues is staggering. The IPL is 10 times larger than BBL and more than five times bigger than all T20 leagues put together.

You May Also Like: Anush Agarwalla - Youngest Indian Horse Rider

India’s manic obsession with cricket provides the IPL massive demographic dividend. A robustly growing economy has been the other pillar on which the league’s monumental success has been built.

Neither of these two factors is under serious threat. From an enterprise point of view, however, it can’t be taken for granted that things will remain hunky-dory forever. India’s ban on its cricketers from playing in any other league safeguards its broadcast rights. But this could come under dispute if players are not sufficiently well-cared for, and rebel.

Participation of marquee Indian players would attract eyeballs from India to these leagues too, which would gain financially and could grow into serious rivals.

The Indian economy is subject to internal and external eco-political influences, and in that sense, not entirely fool proof. So, while the IPL looks impregnable on the face of it, the BCCI has to be alert to challenges that the environment may throw up.

As the title of Intel founder Andy Grove’s epochal book goes, only the paranoid survive.