F1: Motorsport's Men Have Turned Into Boys

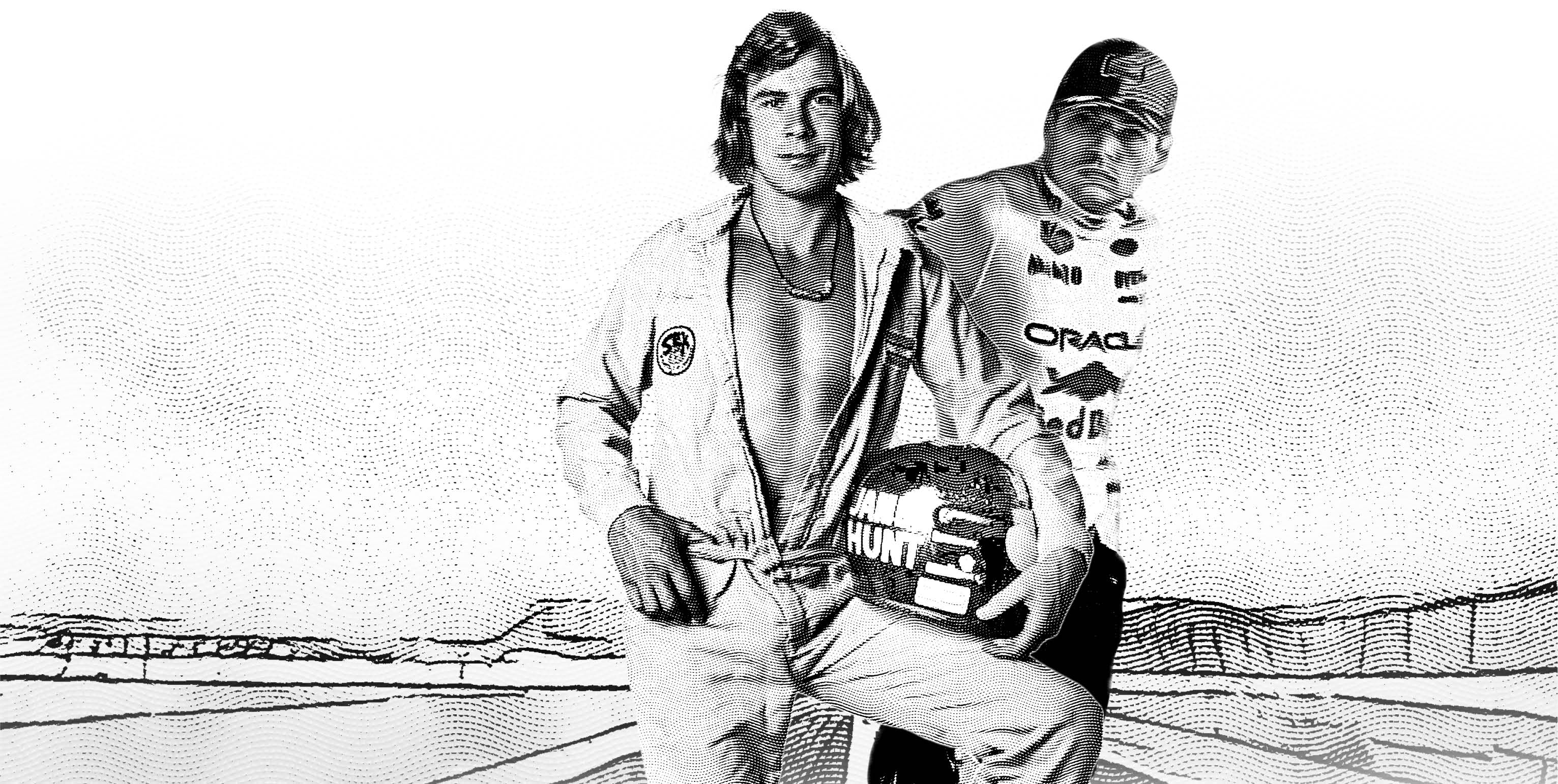

Once upon a time, Formula One Champions were Gods of the tarmac—rugged and hedonistic, dripping with a roguish masculinity that made Hemingway’s bullfighters look like slow-motion amateurs. They swigged champagne, smoked Marlboros and chased women as enthusiastically as they pursued trophies. Think of the debonair James Hunt, who notoriously bedded two flight attendants on the morning of the 1976 Japanese Grand Prix—and still managed to win the World Championship later that day. This was the archetypal F1 hero: part gladiator, part playboy, entirely untouchable.

Today, motorsport looks startlingly different. The modern Formula One champion is less Steve McQueen and more Twitch streamer. Max Verstappen, the reigning champion, was chastised by his Red Bull team for staying up till 3am the night before the 2024 Hungarian Grand Prix, playing sim-racing games online. Verstappen’s obsession with his virtual rig may yield impeccable—and novel—racing lines, but it also paints the current champion as the antithesis of Hunt’s devil-may- care charisma. The new F1 driver is clean-cut, hyper-focused and, frankly, a bit nerdy.

Gone are the days of F1 drivers with a gritty, dangerous allure. Icons like Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost and Nigel Mansell were statesmen of speed, exuding maturity and steely resolve. Larger-than-life figures risking it all on the bends, they spoke philosophically about racing and its mindset. The current grid features cherubic speedsters who play padel and soccer together. Lando Norris shaved his head online for charity. Charles Leclerc livestreams his piano sessions. They’re relatable, marketable, Netflix friendly and disarmingly boyish.

You May Also Like: Anush Agarwalla - Youngest Indian Horse Rider

This is primarily because the stakes have changed. F1 is far safer now, with better technology and infinitely fewer fatalities. The sport no longer demands the ridiculous defiance of mortality that forged the mythos of yesteryear. For instance, 1968 saw four drivers die, yet the show went on. The culture, too, has shifted, and we are less tolerant of aggression and machismo. Hunt’s womanising, Senna’s mysticism and those almighty cigarette sponsorships would feel out of touch in today’s polished, media-savvy paddock.

Drivers today are celebrated less for alpha boorishness and more for reflexes and data-driven precision—metrics that are easily quantifiable thanks to the multiple information streams modern motorsport fans now follow. A race is watched on your television, your phone has various laptimes, a laptop/iPad

nearby will show a different camera angle. Motorsport’s men have turned into boys—and while their prodigious brilliance is undeniable, the sport itself may not feel as gladiatorial.

Traditionally, a driver’s prime arrived in his 30s, when experience, endurance and that elusive quality called ‘composure’ reached their zenith. Think back to the thickly moustachioed Nigel Mansell, spending a life in the sport and finally conquering the championship at 39. Even Michael Schumacher hit his championship-winning dominance in his late 20s and early 30s. The narrative was clear: a decade of grinding through the feeder series and mid-tier teams before maturity met machinery, crowning a champion.

This timeline has been torpedoed by precocity. When Verstappen began in 2015 as the youngest F1 driver ever, he was 17, not old enough to drive home from the racetrack—or to drink the champagne sprayed on the podium. Sebastian Vettel, another Red Bull wunderkind, locked in four championships by the ripe old age of 26. What does that say about the modern driver? That raw speed and instinct—skills honed in karting tracks before puberty, and now perfected in cutting-edge simulators—trump the patience and wisdom that once defined ‘greatness.’

Part of this shift is thanks to Schumacher himself, the patron saint of driver fitness. His focus on physical preparedness transformed F1 into a sport where a beer-gut began to be seen as ballast, and physical endurance was forced to keep step with mental acuity. Fast-forward 30 years, and today’s drivers are biomechanically optimised athletes. Take Lewis Hamilton, whose plant-based diet, strict training regimen and state-of-the-art recovery methods have kept the seven-time champion in peak shape at 40. And then there’s Fernando Alonso, defying age and expectations with his podiums, at 43.

Thus, we witness a two-pronged revolution. On one hand, Formula One grids are dominated by fresh-faced teens who treat simulator training like homework and execute split-second decisions like seasoned pros. On the other, drivers of yore would marvel enviously at the longevity of modern titans like Hamilton and Alonso. Today’s sport is both for the boys, as well as old men who refuse to be dethroned.

The question is whether all this science and discipline has come at the cost of raw charisma. Old-school motorsport devotees bemoan how large and heavy and unwieldy modern F1 cars have become over the last two decades, but nobody can argue against the safety of these oversized cars, which routinely allow drivers to walk away from spectacular crashes. Formula One has become a younger sport, but looking at the lap times, and how fully formed young drivers appear, it’s hard not to be impressed.

It is time to start treating these young men with respect. Mohammed Bin Sulayem, president of F1’s governing body, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), tried to curb the drivers from using too many swearwords on the radio, and gave out headmasterly punishments to Verstappen. New guidelines announced this January threaten the drivers with points deductions—and even a possible race-ban—for misconduct violations, which includes swearing. Imagine anyone doing that to Senna.

Ah, Ayrton. My top Senna quote is when the Brazilian superstar spoke about the rain. Rain racing is the ultimate equaliser, reducing high-tech cars to slippery sleds. Visibility disappears, grip is treacherous and drivers must rely on instinct more than telemetry. The faster cars aren’t faster anymore. “Rain puts the cars at the same level,” Ayrton Senna had once said, “but not the drivers.”

In 2024, one of Formula One’s most contested seasons, Max Verstappen of Red Bull dominated in the first half, but the wins dried up: McLaren, Ferrari and even Mercedes all got faster, and McLaren’s Lando Norris kept closing the gap in the World Championship. At the Brazilian Grand Prix—Senna’s home race—Verstappen found himself starting the race from way back on the grid.

Then the heavens opened.

Verstappen took flight. He sliced breathtakingly through the field. By the end of the first lap, he had swooshed from 17th place to 6th. This was vintage Verstappen, relentlessly slaying rivals by taking the outside of Curva De Sol, and throwing his Red Bull fearlessly—and jawdroppingly—around the Senna S, making the rain seem ornamental. His Turn One moves on Hamilton, Gasly and Oscar Piastri—one of the top defenders in racing today—were gorgeous.

Each overtake was a testament to his unerring instincts and exquisite car control. As rivals struggled with aquaplaning and dashed into the pits, Verstappen stayed out, reading the grip like a maestro reads music. Once he got the race lead, he reeled off seventeen fastest laps in a row, sealing the legend. This wasn’t just a victory; it was a display of confidence, artistry and pure audacity. In that downpour, Verstappen didn’t just win, he conquered—finishing ahead of the other drivers by nearly 20 seconds.

With that championship-deciding drive, Max Verstappen showed who is still boss—reducing his rivals to fight for second place. The 27-year-old demonstrated that the sight of one driver audaciously overtaking another, on an unlikely corner of a soaked track, can never get old. Age is, after all, merely a number—like the digits on a speedometer. It doesn’t matter how many seconds you win by. All that matters is staying ahead.