Inside Sunhil Sippy's Home, Where Quiet Means Everything

Like his work, Sunhil Sippy’s home is a sepia-toned still—full of character and quiet intimacy

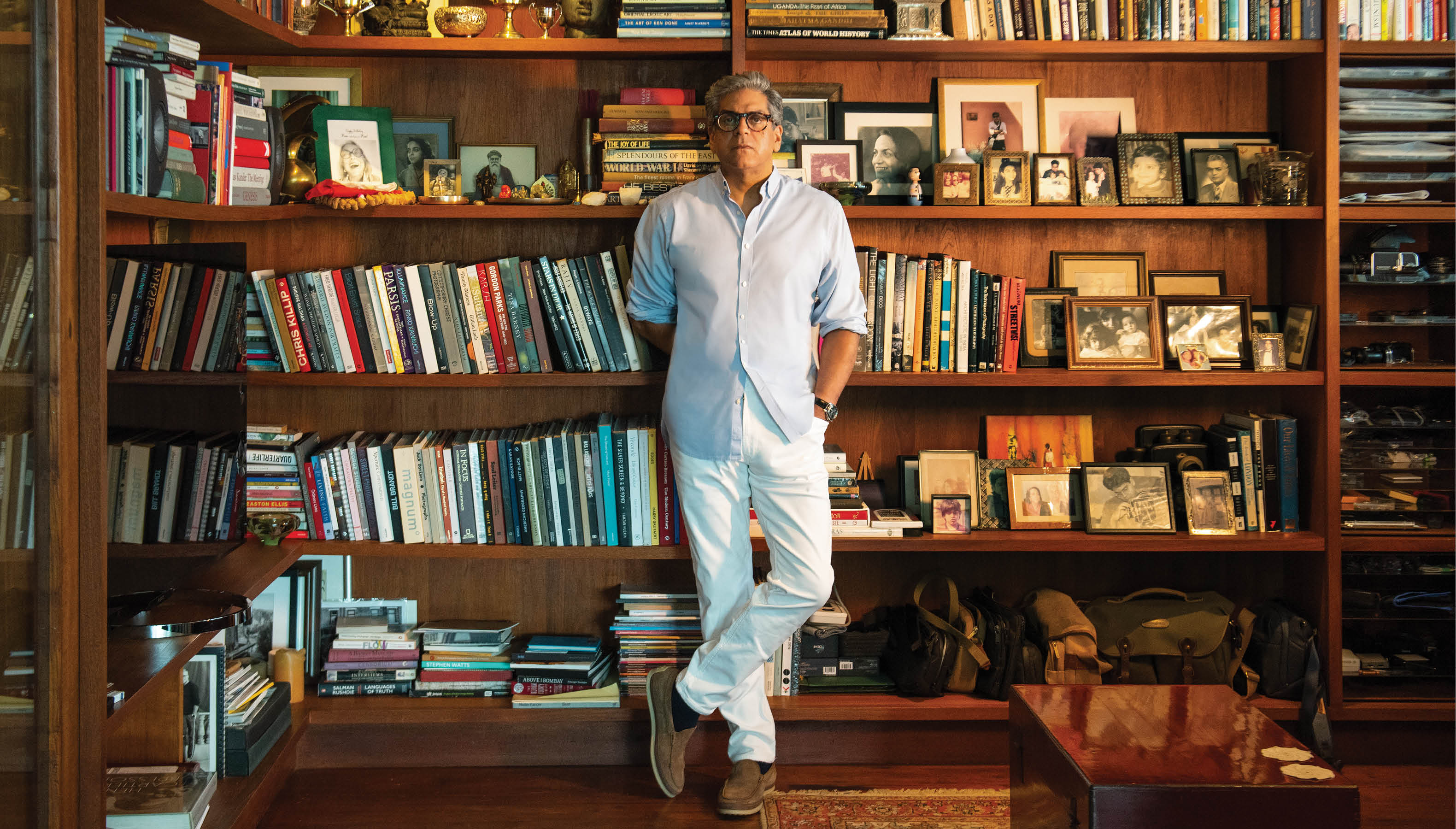

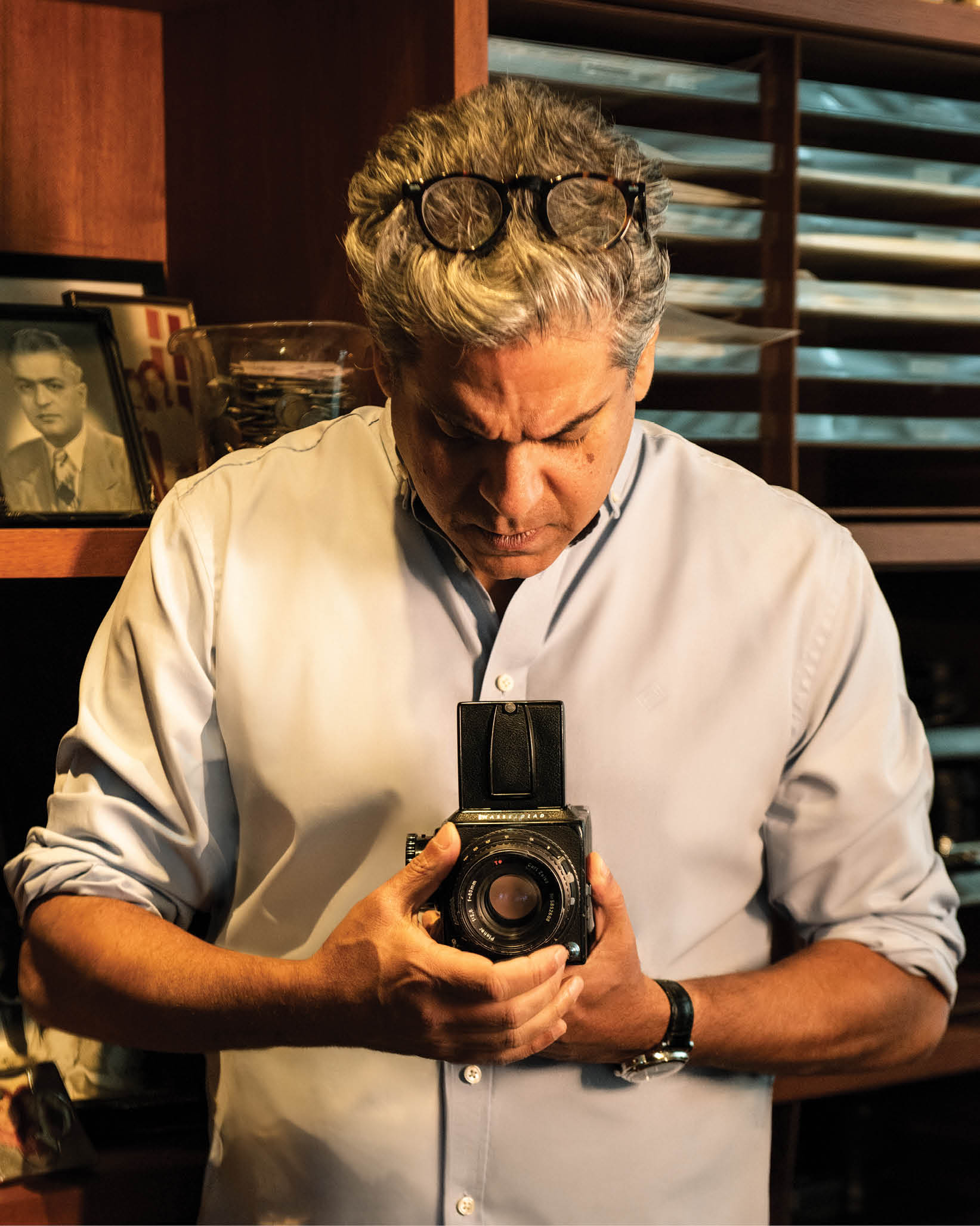

STOREYS ABOVE MUMBAI’S CEASELESS ENERGY, BEHIND DISCREET GLASS FAÇADES AND FILTERED SUNLIGHT, LIES a home that defies the sterility of modern high-rise living. Filmmaker and photographer Sunhil Sippy’s sanctuary is a personal narrative—an evocative composition of texture and memory; a man cave for the discerning aesthete that is cinematic, cultivated and soulfully lived-in. It's not a showroom of masculinity in the traditional sense—there are no whisky decanters or taxidermy trophies.

It’s something infinitely more elusive.

To call it a “house” feels reductive. This is a space that has evolved—through missteps, improvisations, collaborations and emotional fidelity—into a deeply personal sanctum of serenity. More than a home, it is a cocoon: soft-edged, cerebral, unflinchingly personal. It’s a place that captures the tension between the slick anonymity of new-age Mumbai and the nostalgic pull of old-world tactility. When Sippy first moved in 14 years ago, the apartment was a skeletal shell—a box of right angles and builder-grade finishes. It was a move from the vintage charm of South Mumbai's Carmichael Road and then Colaba, to a modern behemoth that was first very much alien to him. Today, it reads like a sepia-toned film still, burnished with character and layered in intimacy.

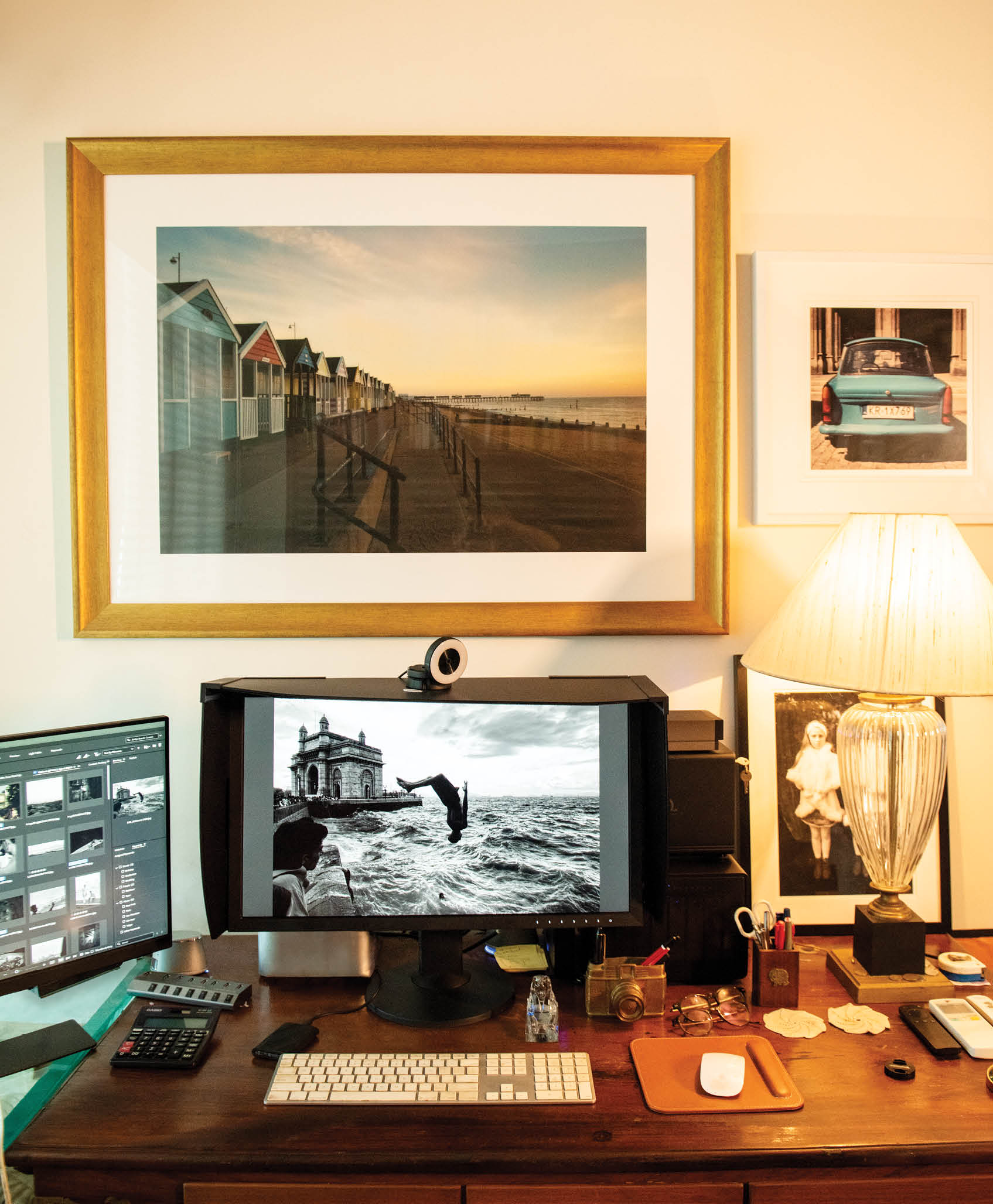

Tucked into a quieter corner of the home, Sippy’s study is where the chaos of creativity finds its calm. Framed by floor-to-ceiling shelves evolving on their own terms and lined with dog-eared books, vintage cameras and framed family moments, the room is tribute to the stories that shape him. At its centre sits an old chair and a no-nonsense desk armed with a mammoth editing rig—his portal into worlds both real and imagined. “It sounds silly, but the only real indulgence I have is sitting at this desk, in the chair that I bought nearly 20 years ago. It’s falling apart but I can’t get rid of it. It’s because I sit there 90% of the time that I’m in the house,” he says.

In the main living areas are wood floors—natural, not engineered—that crackle with imperfections, the kind of artisanal distress that speaks to time and touch. “I love every single crack,” Sippy says, with reverence. “If you come here in the evening, there is no more peaceful place on the planet. The intent was to make it warm, serene, peaceful, and a place where I could work with quiet. And quiet means a lot to me.”

His collaboration with architect Anand Patel brought refinement to the space’s final leg of transformation. “It’s the last 30% that’s the magic,” he notes.

The apartment itself isn't defined by clichés of leather recliners and television screens. Instead, it’s an enclave of considered charm: art that speaks in sotto voce, objects that have absorbed stories simply by existing alongside them, elegant furniture, smatterings of silverware and rosewood side tables handcrafted by his close friend, Priya Aswani. “Every time I touch this table, I just feel so happy that I commissioned it... even if it burnt a hole in my pocket. I'm just grateful that I did things, even when I didn't have the money, because they last forever.” Sitting atop the table is an Asprey ashtray, unusual for the brand to say the least, but with the weight of a life lived across continents. “That ashtray has been around since before I could walk, it was one of two,” he says, eyes glinting. “It moved from our home in London to our old Bombay home, and now, here. I need it near me.”

Then on a coffee table is an extravagant collection of vintage matchboxes, many of them lovingly collected by his mother during the hedonistic heyday of 1970s London. Names like Tramp, Tokyo Joe’s, Ménage à Trois, The Audo, Fogo de Chao, and the Grand Hyatt, among scores of others, crop up on their faded surfaces—relics from a glamorous, analog past where people talked, danced, smoked and lived out loud. “They trigger stories,” he reflects. “You don’t realise the value when you collect them. But years later, they speak volumes.”

THIS IS NOT A MUSEUM, THOUGH IT could be. Nor is it a showroom, though its details could belong in one. It is a gentle rebellion against trend-driven design. There’s a languid luxury to it, where the hours slow and objects breathe. A kind of curated chaos that only the deeply stylish, or deeply sentimental, can pull off.

Much like the home itself, Sippy’s philosophy of display is quietly anarchic. “It’s like tossing things up in the air and seeing where they land,” he shrugs. “I don’t think about it too much.” But beneath that nonchalance lies a master’s eye—for colour, for emotion, for spatial rhythm. His family photo wall at the entrance of the home, for instance, might appear randomly cobbled together, but its half-inch gaps and riot of mismatched frames hold subliminal logic: it’s a cacophony, yes—but a deliberate one. The stories pour out—of trading two of his own photographs for paintings belonging to his friend, creative director Cyrus Oshidar, which now look like rare treasures after Sippy’s framing wizardry.

The art in Sippy’s home is not a collector’s indulgence—it’s a personal pantheon. “I’m not interested in worth,” he says, flatly. “I just need a connection.” Here, in this haven of contradictions, an "utterly grotesque ice bucket"—which no one likes, including himself—sits unapologetically at the bar counter. On the opposite wall, the contemplative calm of Mehlli Gobhai holds court—his abstract forms lending the space meditative gravity. Plucked from the artist’s personal sketchbook, the piece exudes an intimacy that makes it one of the filmmaker’s most cherished possessions. “I can’t take my eyes off it,” he says. “It makes me so flipping happy.”

Then there are the emotionally raw figuratives of Lalita Lajmi, pulsing with feminine mystique and layered familial memory;

the textured, almost breathing lines of Jogen Chowdhury that feel like whispers etched into canvas; the narrative wit and subtle irreverence of Sarnath Banerjee; and the brooding, intimate gaze of Gigi Scaria—each voice distinct, yet collectively weaving a powerful tapestry of contemporary Indian expression.

ON ANOTHER WALL HANGS A limited-edition photograph from Rebecca Norris Webb’s Night Calls series—a memento from a workshop in Mexico with her and Alex Webb that left a deep imprint. “Again, I had a relationship with them,” he says. “So I said, f**k it, I want to own one of their works.”

There’s also art that challenges him—the Pradiptaa Chakraborty, for instance, that hangs above the dining table. He dreams of a change, but refuses to part with it because of the way its moody reds light up the room at dusk, infusing it with a pulse of warmth. “Most people adore it, but I've often thought of replacing it with something more monochromatic,” he admits.

If there’s one movie prop he’d love to add to his home, it would be the iconic white shoes worn by Peter Sellers as Hrundi V Bakshi in The Party—Blake Edwards’ cult 1968 comedy classic. With the original suit from the film soon set to go under the hammer, perhaps the legendary shoes will also step into the spotlight. And if they do, who’s to say Sippy won’t be a contender at auction?

From the terrace—his perpetual muse courtesy of its sweeping city views—he’s captured over 300 moods of the ever-morphing Mumbai skyline, turning a singular view into a psychological self-portrait, a habit that mirrors the philosophy behind his photography: that the gaze, whether turned on the city, a stranger, or a staged campaign, is nothing more than a mirror of one’s own spirit, shaped by every moment lived, every heartbreak, every book read, every misstep, every misfit, and every attempt at authenticity in a world addicted to polish.

And now, as he attempts to recreate this spirit in Goa—where he’s contending with a modern shell that stubbornly refuses to age or leak romantically like the Carmichael Road house of his past—he’s once again grappling with that delicate act of infusing soul into cement, trying to conjure warmth and texture where there is none, because homes are slow-burn confessions created by time, accidents, flaws, and an intuitive eye that knows exactly when something just belongs.

The soundtrack Sippy chooses for his home in Mumbai is also quite telling: Rachmaninoff one day, Miles Davis the next. Music that, like the home itself, lives between structure and improvisation. “Too much comfort dulls the edges,” Sippy muses. “This space, with all its tiny imperfections, pushes me. It keeps me thinking. It’s never finished—and neither am I.”

And perhaps that’s the defining essence of this quietly brilliant home: it’s alive. It’s a room that listens, forgives, protects, and provokes. A sanctuary, yes—but also a crucible. A place where there is beauty, not because everything fits just right, but because some things don’t. And in those spaces—in that tension—Sippy continues to create. Relentlessly. Resolutely. Refined by imperfection, and better for it.

Credits

Words: Jeena J Billimoria

Photography: Raghav Goswamy

To read more stories from Esquire India's August 2025 issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest newspaper stand or bookstore. Or click here to subscribe to the magazine.