Making Room For Joy: Inside Gautam Sinha's Gurugram Home

Nappa Dori founder Gautam Sinha’s home echoes the minimalism of his brand. But lately, he’s letting a little colour in

THE MOMENT YOU STEP INTO GAUTAM Sinha’s home in Gurugram, there’s an immediate sense of order—but not the rigid,

self-conscious kind. It’s not austere or sterile. It’s warm, deliberate and unmistakably personal, much like the man himself.

Sinha, the founder and creative director of Nappa Dori, the leading Indian luxury leather and lifestyle brand, greets you in a

brown corduroy jacket from his own line, white T-shirt, jeans and a vintage cap. Coffee in hand, he looks at ease—like someone completely at home in his space, because he’s built it on his own terms. You can tell this isn’t a house designed for guests. It’s a house built for him.

It’s minimal, but not bare; and the first thing that hits you is the symmetry and the clean lines. It’s Dori in brick and mortar:

warm and quiet. With his father in the forces, Sinha grew up everywhere. Perhaps the most constant thing in his childhood was the beloved Nappa Dori trunk that’s everywhere today. However, his love for leather came later in life—after his time at the National Institute of Fashion and Technology (NIFT) and a short stint at a leather export company in his early 20s.

An off-kilter charm defines his house. The lounge, to the left, is the kind of room you want to sink into. A famous black Eames chair sits by the corner, because nothing speaks Sinha more. “I’ve always endorsed minimalism and been really fond of it, and I think that’s a way of life in my head,” he says. His design philosophy relies heavily on simplicity and functionality and is often compared with Scandinavian and Japanese aesthetics.

There are a few framed posters—Velvet Underground, Louis Vuitton—resting coolly against the wall, never hung. A Wart

169 hol print leans casually on the floor. Sinha doesn’t like things on walls. Maybe it’s the permanence of it—the commitment of a nail through plaster. “I prefer them grounded,” he shrugs. The same logic applies to lighting. No ceiling fixtures, no wall sconces.

You may also like

“Wall lighting gives me the ick,” he says, laughing. “I like it warm, low and from the ground up—everything that feels hygge.”

LAMPS OF ALL SHAPES AND SIZES POPULATE THE room. “You should see this house in the evening,” he says, pointing around. “It completely transforms. It’s so cosy with all the lights and the lamps. This is an evening house, trust me.”

To understand this house is to understand his obsession with things—not in a hoarder’s way, but in the sense that every object here tells a tale. You can read Sinha’s life like a scrapbook through his objects. A line of vintage percolators sits in the kitchen—some clunky, some sleek—each one picked up during his travels. Coffee, it turns out, is his soft spot.

You may also like

“I don’t know how my love for coffee started, honestly, but it’s my favourite thing in the world. I actually started Café Dori because I didn’t get a good cup of coffee anywhere in Delhi eight years ago,” he says.

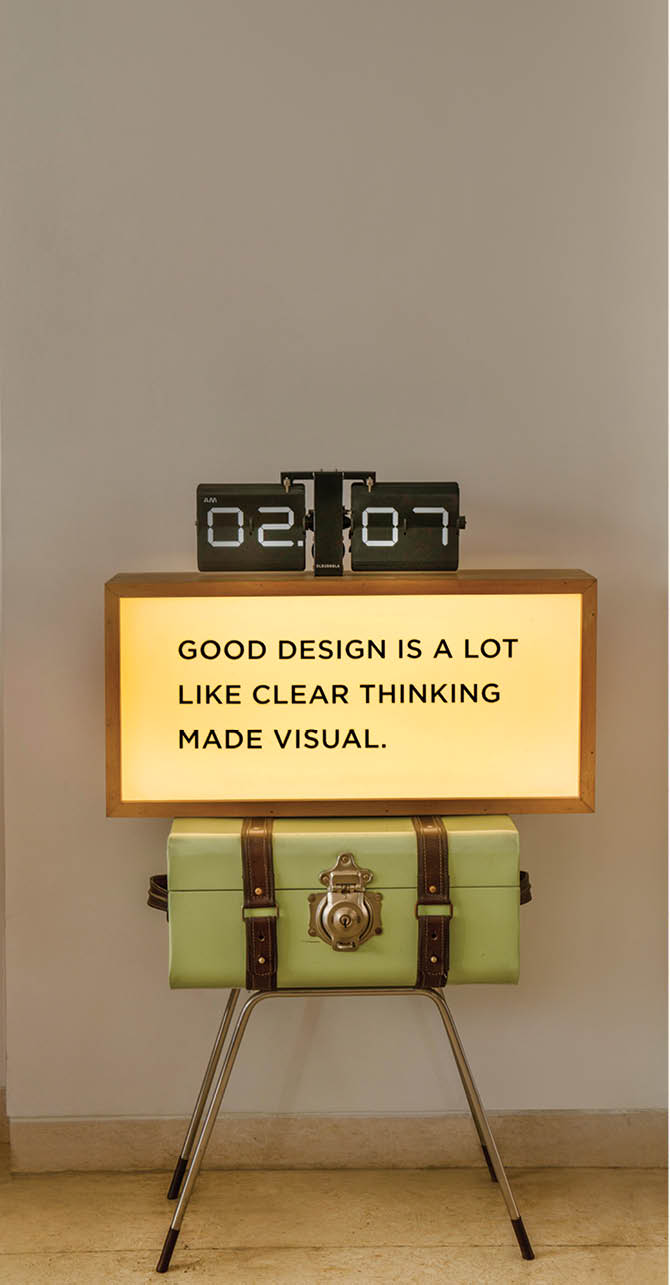

“Coffee equipment is something which is very close to my heart. I love the process and mechanics of it.” This fondness for machinery—for tactile, kinetic design—is everywhere: in the analog clock that rests atop a Nappa Dori trunk, in the growing collection of vintage lighters lined up like little totems of fire and form.

Nearby, a crate of vinyls lies stacked. There’s Marvin Gaye, Al Green and George Shearing. Billy Joel plays on his projector. “Those vinyls have travelled with me from one house to another for years. I shuffle between London and Delhi a lot, but this feels like home,” he says, almost absent-mindedly, flipping through them.

Just then one wonders if there’s anything he truly couldn’t part with. He pauses, then answers: “Honestly, no. I think it would be kind of therapeutic to start again. I’ve come to a place where I’m at peace with who I am.”

He started Nappa Dori in 2010 with just one design: a hand-stitched leather belt. “It was something personal. Something that felt honest.” The name came naturally—‘Nappa’ for the supple leather he works with, and ‘Dori’, the Hindi word for thread. From a tiny workshop in Delhi, the brand has now gone global, with stores in Sri Lanka, the UK and the UAE, and a devoted following across continents. “It’s been 15 years, can you believe it?” he says, reflecting on his journey. “I feel more structured, but I have no bloody clue where I’m going to go in the next 15 years. Design will keep evolving.”

You may also like

There’s no hard divide between Gautam the man and Gautam the maker—it all bleeds into one sharply drawn silhouette. “Even when I’m asleep, I’m thinking about Nappa Dori,” he says. And it shows. The air conditioner, for instance, isn’t just tucked away—it’s tailored. Swaddled in a custom leather sheath, stitched in classic Nappa Dori fashion. “Air conditioners are ugly,” he shrugs, like that settles it. And maybe it does.

TO CALL THIS SPACE A MAN CAVE FEELS LIMITING—this isn’t your leather-soaked, testosterone-heavy den. It’s

more of a “chaotic nest”, as Sinha describes it. “A completely chaotic, synchronised chaos,” he grins. “This disaster is definitely all me.”

He’s joking, of course—the space is anything but chaotic. Every surface, every finish, every choice speaks the language of someone who doesn’t separate life from design. It’s that way not because a designer curated this house, it’s because the designer lives it.

“I don’t think I could ever let someone else design for me,” he says, matter-of-factly. “That’s a part of my DNA—how can I part with that?”

And yet, Sinha admits his aesthetic has evolved over time. “I’ve always endorsed minimalism, but lately I have been open to a bit of maximalism, of colour. Maybe it’s age.”

He pauses, then smiles. “I like feeling joy in my space. Whether it’s minimal or maximal, it just has to feel happy.”

To read more stories from Esquire India's May-June 2025 issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest newspaper stand or bookstore. Or click here to subscribe to the magazine.